Detours, data, and the reality of a scientific career in India

Karishma Kaushik’s career trajectory explains why science in India is shaped as much by structure as ambition.

By Saishya Duggal

| Posted on February 11, 2026

Dr Karishma Kaushik’s career has unfolded at the intersection of ambition, contingency, and science systems that often lag behind the people they train. With an MBBS, MD in microbiology, and a PhD, she has worked across clinical medicine, infectious disease research, and science administration, eventually leading a national life-science programme she once only dreamt of being part of.

On paper, it looks like a linear ascent; in practice, it’s anything but.

At one point, mid-career and highly regarded, Karishma found herself staring out at her neighbour’s garden, drawn to a bird of paradise flower in full bloom. It looked vivid and complete, everything her “dream job” was supposed to feel like, but didn’t. That dissonance eventually pushed her to write The Real Deal, a guide for aspiring girl scientists that lays bare what life in science actually looks like from the inside.

“It was cathartic,” she said of the writing process.

Karishma at a biofilms event that brought together over 250 international researchers in the field

Finding science by staying open

Karishma is quick to dismantle the idea of a calling. She didn’t grow up wanting to be a scientist, let alone imagining herself developing antibiotics or curing tropical diseases. “I didn’t decide any of that when I was nine,” she said.

Her entry into STEM, she explained, was shaped by available opportunities rather than childhood conviction. What followed was discovery by exposure. She took up an MD in microbiology because it was the best seat available, a pragmatic choice that led her to study chickenpox strains in India. The award-winning research, which focused on genetic analysis of chickenpox strains, helped explain why breakthrough cases persisted despite vaccination, and allowed Karishma to independently collect over 100 clinical samples to compare wild-type and vaccine strains of the virus. That experience (working closely with real-world disease data) eventually nudged her towards a PhD in the United States.

It’s a lesson she returns to often: figuring out what you are good at, and what you want to do, rarely happens early. It takes time, experimentation, and a willingness to let experience refine ambition.

Endurance as a scientific skill

Ambition, however, operates within limits. After getting married, Karishma moved to California in 2008, at the height of the global recession, and ran headlong into stalled progress. PhD rejections piled up. Visa restrictions tightened. Political rhetoric around “Buffalo, not Bangalore” hardened the landscape.

For nearly two years, she volunteered at a local research lab while trying to stay afloat. Eventually, she secured a PhD position in Texas. Looking back, she frames that period not as an aberration but as part of the scientific career itself. Endurance, she suggested, is an unspoken requirement: you have to stay in the system long enough for opportunity to reappear.

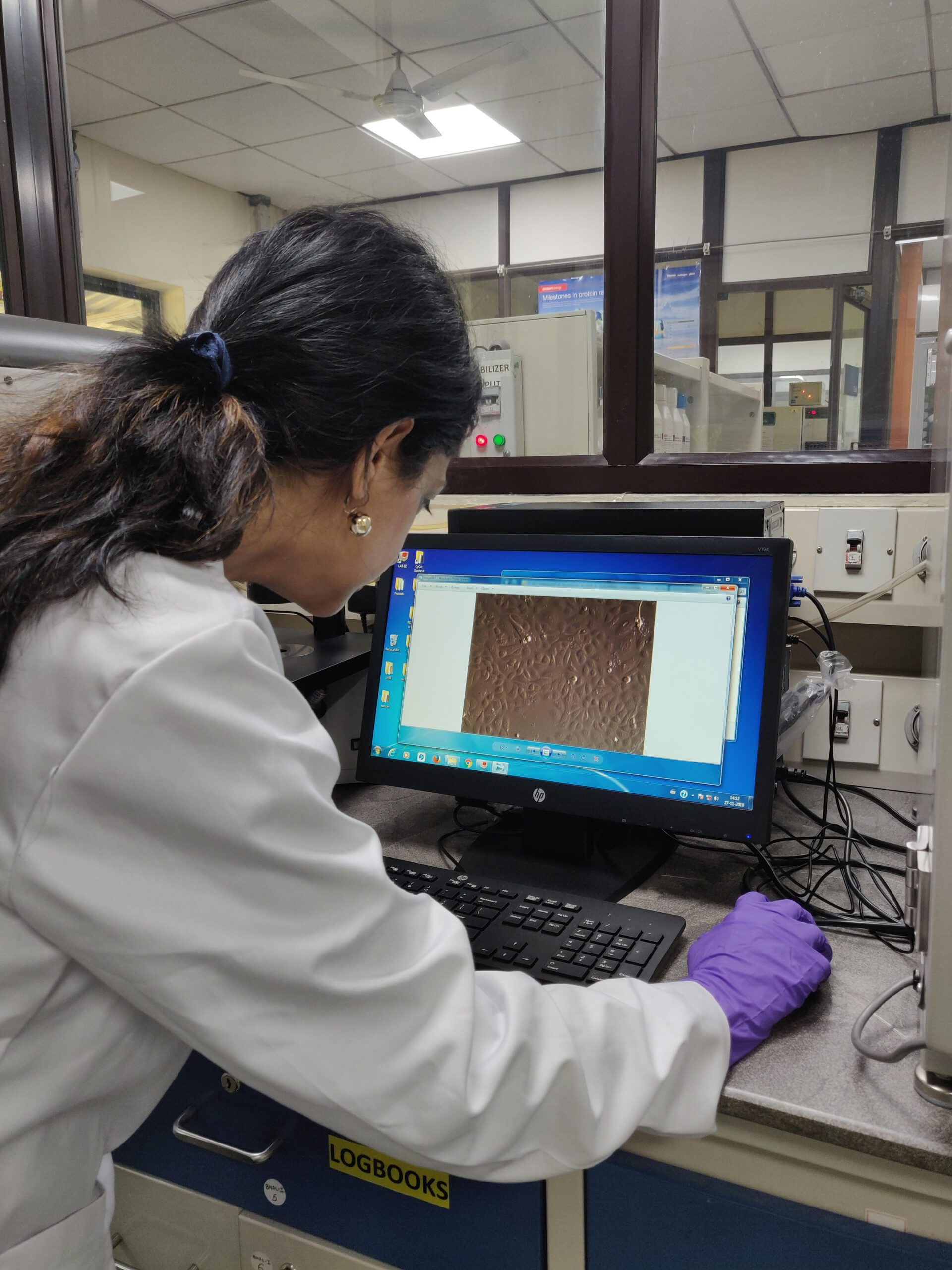

Karishma absorbed in her research

Support mattered. She speaks warmly of her husband, who relocated with her so she could pursue doctoral research. “A woman’s career doesn’t survive on encouragement alone,” she said. “It survives on proactive decisions.”

Little Karishma with a stethoscope; unbeknownst to her, she would end up a physician-researcher

Motherhood and the cost to science

Karishma had her son while she was pursuing her PhD. Her programme had no maternity leave policy for doctoral researchers. None.

“I was left to craft my own maternity leave,” she said. She paid a friend to cover her teaching duties, the work that funded her stipend, so she could take six weeks off.

It shows up elsewhere too: in hiring decisions, expectations of long hours, and assumptions of constant availability. “What starts as academia’s two-body problem becomes a three-body one,” she says, “because there’s a baby now.”

Research, she notes, shows that women scientists without children often track closely with male peers. The divergence begins sharply after motherhood. When women drop out or stall, it isn’t just personal loss, years of training and public investment exit the scientific system.

Nonetheless, Karishma studied biofilms (communities of bacteria that are a major reason why infections become hard to treat) as part of her PhD, and her work (a mix of microbiology and physics) revealed how small changes in the bacteria’s environment can affect how these communities form, and how resistant they become to antibiotics.

Returning to India, running into structure

Through the Ramalingaswami Re-entry Fellowship, Karishma returned to India to contribute to research. She initially set up an independent research group focusing on biofilms in chromic wounds (like those in diabetes or hypertension). Because bacterial biofilm made these infections resistant to treatment, the wounds’ delayed healing was becoming a major healthcare burden for patients and caregivers across India. Despite her well-meaning research topic, Karishma was thwarted into more systemic issues (like scouring for institutes that could host her fellowship) because of new governance changes that had shook things up.

Karishma at an event as a science communicator, a role she feels deep affinity towards

That’s when what she calls the “position gap” became apparent.

Permanent academic jobs were scarce, tied to retirements, and concentrated in specific cities. Because she was geographically anchored to Pune, due to her husband’s job and family responsibilities, options narrowed quickly. Unlike tech or IT, academic science offered little flexibility.

The result, she says, is that many women end up in temporary, unstable, and low-paying roles because those are the only ones compatible with their lives. Over time, this creates a cycle: women fill these jobs because they exist, and the jobs persist because women keep filling them.

It’s heartening to see that despite the obstacles, Karishma’s research (by then at a state university) stayed public-spirited: to support her belief in “open science”, she and her team created a publicly accessible database (called B-AMP) of anti-microbial peptides designed to target bacterial biofilms, publishing thousands of peptide structures to help researchers develop new treatments for infections that were drug-resistant.

Karishma in the US, pursuing her PhD while expecting her son

Leadership, power, and performance

Her most defining pivot came when she took up what had once been her dream role which was leading a national life-sciences programme. The position placed her in rooms where decisions about science, funding, and leadership were being made; it empowered her to facilitate science careers in India through networking, mentorship, and training.

It was there that she encountered the “woman card”.

“They want you to lead like a woman,” she says. “Soft, empathetic…but they don’t prioritise performance.” She recounts comments directed at her: “Okay, you’re done. You can leave now.” Or, “You should understand what it takes for a woman to earn respect in society.”

What disturbed her most was the assumption that women’s careers were optional. “No one would say this to a male leader,” she says plainly.

She is also self-critical. She admits she didn’t ask the right questions before taking on certain roles, about organisations without HR systems, unclear funding horizons, or expectations that extended far beyond her remit. It’s advice she now offers young women: ask hard questions early, and understand exactly what you are responsible for.

Holding science together with humour

Karishma’s voice, both in conversation and in her book, moves easily between data and lived experience. That duality is part of her strength as a science communicator.

She recounts a stint at the state university in Pune where, for nearly two weeks after campuses reopened post-COVID, her department had no functioning water supply. No usable restrooms. She used a nearby hotel’s facilities instead, buying coffee each time. “The most expensive public restroom arrangement of my life,” she says.

“At the time, I was anything but stoic,” she adds. Humour, she insists, is how dignity is salvaged when systems fail.

Despite the gap between expectation and reality, Karishma doesn’t sound jaded. Currently on a career hiatus, focusing on her health and her teenage son, she is exploring independent consulting and thinking about contributing to science in new ways — including the idea of becoming a science ambassador of sorts.

If The Real Deal leaves readers with anything, it is this: careers in science are rarely linear, and detours are not evidence of failure. They are part of how the system actually works. Life in STEM rarely follows a straight line. But as Karishma Kaushik’s story shows, it is often the detours that make the deal real.

About the author

Saishya Duggal is a public policy and impact consulting professional working at the intersection of tech, finance, and climate policy. She has undertaken projects with the UP Govt., the World Bank group, and Indian NBFCs. A graduate of Delhi University, her work emphasises the value of STEM in policy and its implementation. Her previous professional stints include those with Invest India and Ericsson.

Add a Comment