Posted on August 21, 2023

Fighting in the dark: How ASHAs in Bihar strive to keep kala-azar at bay

By Saumya Kalia

Overworked and underpaid, grassroots health workers continue to go door to door, persist in screening of people with symptoms, and constantly monitor them for years together in their bid to eliminate the disease

ASHA workers of Dariyapur village (Photo courtesy of DNDi)

Mumbai, Maharashtra: Ashima Kumari* has run away. The rumour reached Richa* as she stepped into Salha, around 40 km from Bihar’s capital Patna. Wearing her custom uniform — a pink and purple saree with letters ‘ASHA’ stitched on the border — Richa had started out from her home in Ward 15 by foot at 7 am to make her rounds of the area with over 1,000 people in 248 houses.

Ashima’s (17) home was the last stop on her route before lunch. An Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) for 18 years now, Richa has been looking after Ashima for the last 14 years (since 2009) after the district hospital diagnosed her with Visceral leishmaniasis, also known as kala-azar. Though Ashima recovered, she contracted Post Kala-azar Dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) in 2016, which relapsed twice later. The girl now has brown and red patches on her face, a sign of PKDL relapse.

The PKDL patients are reservoirs for the leishmaniasis parasite, which enters the body through the bite of minute sand flies and causes kala-azar. India accounts for over 80% of kala-azar cases globally, with Bihar reporting about 90% of them. It can be fatal in 95% of cases if left untreated, and is the second deadliest parasitic disease, next only to malaria.

India accounts for over 80% of kala-azar cases globally, with Bihar reporting about 90% of them. ASHAs are the first line of defence against the disease (Photo courtesy of DNDi)

About five to 10% of kala-azar cases develop PKDL, although some do not have such prior history. The lesions develop anywhere between six months and five years. However, lesions were reported within two months in Chapra in Saran district and some villages, local healthworkers said.

Despite strong surveillance, early diagnosis, and new treatment regimes, India failed to meet the deadline thrice before — in 2015, 2017 and 2020. If untreated, even one PKDL case can trigger a kala-azar outbreak — a tripwire India wants to avoid by adopting best practices to eliminate the disease by this year. Even people successfully treated for kala-azar can infect others if they develop PKDL, a 2019 study found, implying that even when kala-azar is controlled, the transmission of PKDL continues unchecked.

ASHAs are charged with the task of solving a central piece of the puzzle: rigorously screening and managing PKDL cases. In fact, Kala-azar presents a unique challenge as illness lingers even after recuperation. The ASHAs’ ‘cure’ is then disguised as care, as they straddle the limits of medicine.

The first line of defence

The first PKDL case that Richa saw was within her family, when her nephew developed skin lesions. The endemic districts in Bihar are warm and sticky; vegetation and poor housing create the perfect environment for sandflies to breed. Kala-azar is termed as the disease of the poor, who have no clothes and shelter.

Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal also witnessed a high Kala-azar caseload until 2017, when India ramped up screening and vector-control initiatives. The PKDL cases have hovered in the range of 600-800 since 2020 (across the four states where it’s prevalent and cases are notified). Healthcare workers, however, hint at an unfavourable trend: old cases relapsing and new ones rising.

The ASHAs have internalised the gold standard of defence: door-to-door screening and surveillance. First comes fever, often accompanied by loss of weight and appetite, anaemia, and enlargement of the spleen and liver. They are told to watch out for extended stomachs. Skin lesions develop months or even years later.

If the fever persists for more than 15 days, the ASHA concerned will persuade the patient to visit the nearest Primary Health Centre (PHC). Once tested and confirmed, the ASHA will pay fortnightly/monthly visits to check the patient’s symptoms and to take him/her to the PHC if needed. Follow-up check-ups are held in one, three, six, nine, 12, 15 and 18 months.

A 2014 study showed that training ASHAs on managing kala-azar increased the referral rate from less than 10% to over 27%. If not for them, the symptoms are missed or ignored.

Meena Devi (48) of Anandpur Kharauni in Muzaffarpur district has scaly patches on her upper arm, an early sign of PKDL. She visited Paro PHC, some 10 km away, when kala-azar manifested with a fever. She did not visit the PHC immediately during the second bout thinking that farm labour caused fever. Now, focusing on relatively painless marks from PKDL feels like a luxury for her.

“Rural access to medical care and general awareness are different from that in urban areas. Commuting is a challenge. Health workers play an important role in ensuring that the patients reach the health centre,” said Dr Kavita Singh, Director-South Asia, Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi).

ASHA workers in Dariyapur village, Bihar (Photo courtesy of DNDi)

Meena Devi sits on her charpai, pointing at the mosquito net above (Photo – Saumya Kalia)

Fending off trust deficit, stigma

ASHAs create awareness on kala-azar, its symptoms, the need to maintain cleanliness and use mosquito nets at baithaks (small gatherings) organised every month. “People did not understand hygiene or cleanliness earlier, but now they do. Everyone has become samajhdaar [sensible],” said Richa.

The PKDL scars are non-fatal, but they evoke shame. Could that be the reason for Ashima’s disappearance? “Her face is the colour of sindoor and her body has black spots,” Richa murmured.

Gender norms further exacerbate the situation. Families understand that daag (scar) and dhabba (patch on skin) may obstruct the marriage prospects of girls and augur abandonment of married women. Some families thus chose not to engage with ASHAs or report symptoms.

Kala-azar can overlap with other conditions. For instance, HIV patients are at risk of developing it. Sometimes, PKDL scars are mistaken for leprosy in rural areas. Stigma takes on a life of its own, sustained by misinformation floated by local quacks who claim to offer ‘quick fixes.’

ASHAs respond to such cultural anxieties and help people understand all aspects of PKDL, including disability and violence. Their role extends far beyond case detection and management as both diseases morph into social malaises.

However, social support for women who face abandonment and violence remains a gap still. A 2018 study published in PLOS attributed the delay in PKDL treatments to a lack of knowledge and perceived stigma, which “interferes with the therapeutic outcome of the disease through its effects on treatment-seeking behaviour and drug compliance”.

“ASHAs are the messengers. People will not know if ASHAs do not carry information to them,” said Shishu Kumari (38), an ASHA coordinator in Dariapur, from where kala-azar was eliminated in 2017.

Neeta Kumari (32) joined the ASHA workforce in Gaighat block of Muzaffarpur district last year. “Darr lagta hai. Bahut darr lagta hai [It is scary, very scary]… My husband encourages me to work safely, but kaam toh karna hi hain [I have to do the work],” she said about her initial days at the job.

In Baniapur of Saran district, an ASHA facilitator was diagnosed with kala-azar in 2018. But ASHAs like Kumari have overcome their fear, armed with the knowledge that kala-azar is not a communicable disease. Looking on the bright side, she added, “These are our people. I like to work with them and walk around my ward.”

No incentives

The nearest PHC for Richa is at least five km away and takes about Rs 100 both ways via auto. People often refuse to travel citing cash shortage. “We make sure we take them on the same day… Sometimes we pay from our pockets,” Richa said. The state government gives each house is an incentive of Rs 7,000 to report cases, and buy medicines and mosquito nets.

ASHAs are volunteers with a fixed monthly wage (Rs 2,000 to 4,000 depending on the state) and receive incentives for case-specific tasks, including organising family planning meetings, advising on immunisation drives for newborns and taking pregnant women to hospitals.

For every kala-azar or PKDL patient they bring to the hospital, they get only a one-time incentive of Rs 300-500 by the state, though they follow-up with patients for months, if not years. In some cases, these payments are delayed.

Shishu has been awaiting her kala-azar incentive since 2017. Richa has not received the incentive for Ashima’s case yet. “We have tried raising the issue in meetings, but no one hears us,” said Richa, who earns only Rs 3,000 per month.

The custom saree of an ASHA worker in Dariyapur (Photo courtesy of DNDi)

An ASHA worker cycling to work in Dariyapur (Photo courtesy of DNDi)

The lack of incentives is not an invisible deficit. Meena Devi says no ASHA visited her. “There is very little incentive for kala-azar and PKDL. ASHAs already look after a lot of people, and maternal and child care take priority,” says Prakash, who works at Chapra PHC. Public health is a leaking pipe, and ASHAs can plug only a few holes.

Expensive drugs with side effects

Government-mandated VL drug regimes — Miltefosine and AmBisome (single liposomal Amphotericin B) — are administered for PKDL as a 12-week oral regimen. The national guidelines for treating PKDL recommend Miltefosine as a “preferred” first-line drug, and Amphotericin B for patients who have liver or kidney complications, or if they don’t respond to Miltefosine. The cost of the drugs (Miltefosine is Rs 2,500 to 5,000 depending on dosage and AmBisome costs Rs 75,000 to Rs one lakh per treatment with people usually needing 3-4 depending on weight profile) is a barrier to mass treatment. There are also concerns about efficacy and side effects — fever, nausea, eye complications and stomach pain. Stomach pain has forced PKDL patient Chanani Kumar* (17) of Anandpur in Bihta block of Patna district to skip medicine for the last six months, besides check-ups.

Clinical trials by different organisations, including the DNDi, are progressing to develop a safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable treatment regime. But even as kala-azar demands tight surveillance, along the lines of COVID-19 drive, ASHAs operate from a blind spot. They go about their work much like the way stones are laid one on one, on a long road that may never be finished.

Rita Mishra, an ASHA worker in Salha village (Photo courtesy of DNDi)

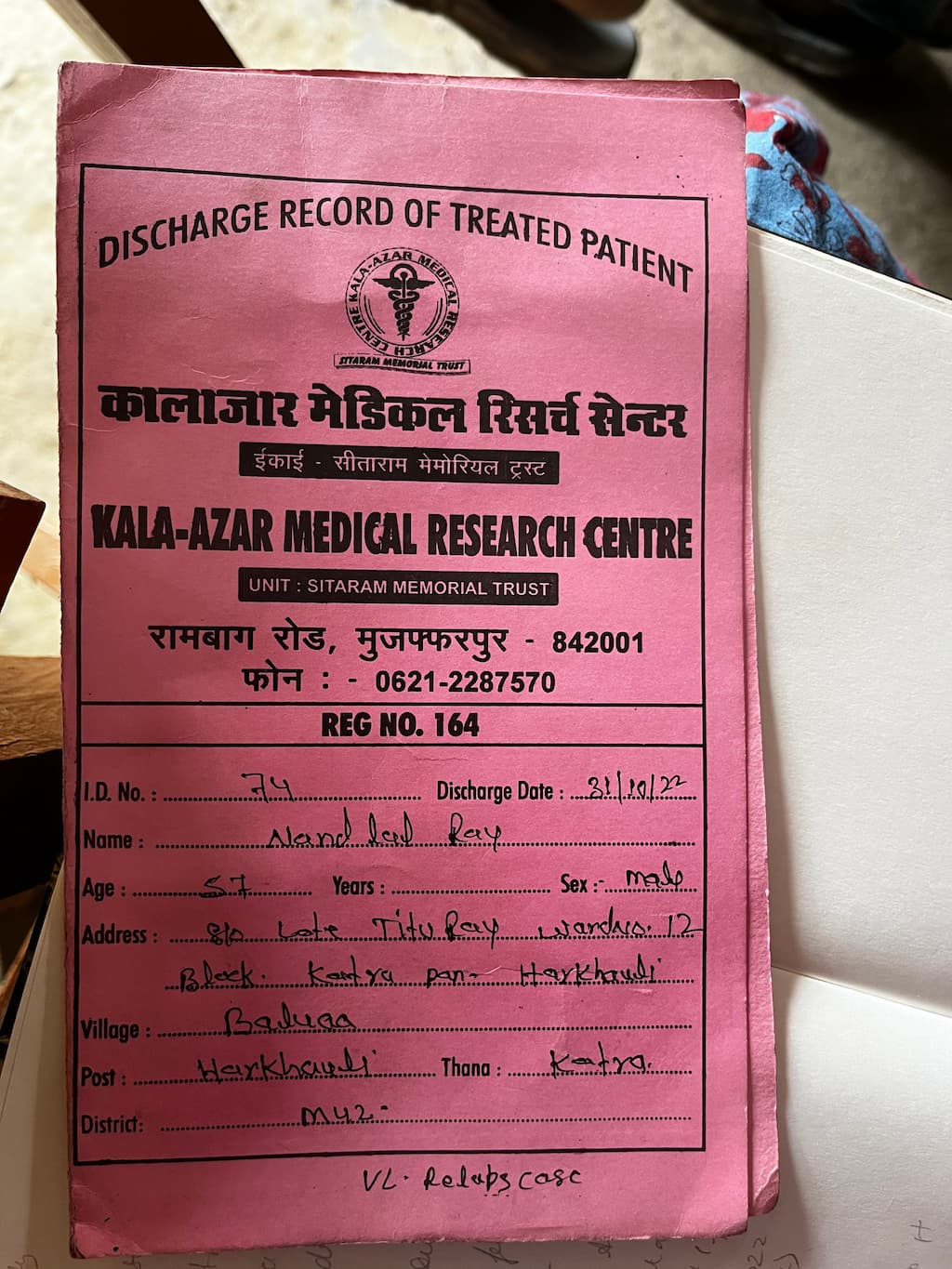

The health card of Nandlal in Paro district (Photo – Saumya Kalia)

The home of Meena Devi (Photo – Saumya Kalia)

Meena Devi has already relapsed twice (Photo – Saumya Kalia)

About the author

Saumya Kalia is a journalist based in Mumbai. She writes about health, gender, cities, and equity.

Add a Comment