March 13, 2024

Foraminifera is her favourite proxy to study oceanographic processes at different timescales

Panchang completed her BSc and MSc in Geology from Pune University and never thought of taking up paleontology, but she eventually did. At the beginning of her career, Panchang was the only woman along with three young men to get selected for a research PhD position for the ambitious BENFAN project at the National Institute of Oceanography (NIO), Goa.

Women in sciences have been sidelined historically, especially in India, where cultural reservations around women overpower their excellence. Hence, going after what you want often requires unparalleled grit and determination. In 2018-19, the Directory of Extramural Research and Development Projects released by the Government of India indicated a decrease in women principal investigators of extramural projects from 31% in 2017-18 to 28% in 2018-2019.

A shaky but defiant start

It was hardly surprising that the research PhD opportunity did not exactly fall into her lap. When Panchang went for the interview to pursue her PhD, her interviewer said, “I have 40 people interviewing tomorrow. If I find a boy and a girl of equal calibre, I will choose the boy because girls are not interested in research. They are seldom interested in careers. They look for good choices for marriage. And when they get married, they get distracted and leave.”

This ill-informed stereotype infuriated her, and she left the room feeling defeated. However, she topped the merit list and was offered the spot with the clause that she would not quit in the middle of it.

Twenty years ago, Dr Rajani Panchang (44) was working in the Irrawaddy Delta in Myanmar when she discovered an oddity. The type of foraminifera, commonly known as forams, she encountered suggested the presence of coral reefs in the delta. She immediately shared her findings with her all-male bastion in the lab and they dismissed it. She then turned to her research guide/supervisor, who encouraged her to tag the locations anyway.

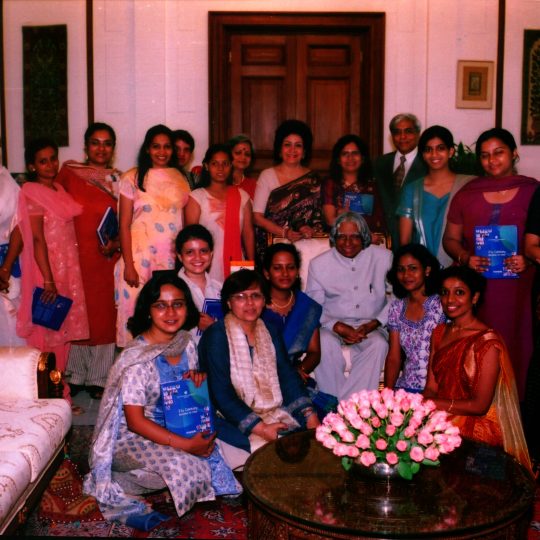

As Guest of Honor at a Lila Poonawalla Foundation event

“Corals cannot survive in areas with lots of sediment and riverine influx, turbid, and low salinity waters. I was able to mark some locations on the delta shelf with coral reef presence. Further examinations found that even in a delta with so much incoming freshwater, there was a submarine belt on the ocean floor, which was isolated from active sediment deposition. The local current systems were transporting the sediments along the coastline. That was why the coral reefs were getting protected. Many of these locations had fossil reefs, indicating that in the past, coral reefs flourished there in patches, and when sea levels all across the globe rose because the last glacial era ended, these reefs got submerged [Panchang et al, 2008],” she explains.

“Mangroves play a very big role in protecting coral reefs that occur deeper. Wherever there are mangroves, they will hold on to sediments, and not allow the sediments to smother and destroy the coral banks,” she adds.

If it were not for the forams that Panchang discovered, this biodiversity resource in the delta shelf of Myanmar would have stayed hidden away from plain sight.

Dr Panchang with her students at Savitribai Phule Pune University

Panchang, an oceanographer specialising as a micropaleontologist, is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Environmental Sciences, Savitribai Phule Pune University (SPPU). “If I have to introduce myself, I would say I am an oceanographer studying different kinds of oceanographic processes at different timescales using a proxy called foraminifera. And yes, my forte is taxonomy, though I do use different attributes of foraminifera such as its abundances, chemical and isotopic signatures to unveil past climates and predict the future.”

“So whatever research I do has important implications in the planning and management of ecosystems for the future. Many such published palaeoclimatic/palaeoenvironmental data from across the globe help the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to make predictions and make action plans to combat climate change.”

Foraminifera are single-celled organisms with enormous potential to trap the signatures of past climates. They also serve as indicators of change in marine environments ranging from brackish water, deltaic estuaries, and coastal ecosystems to the deep seas.

Forams are everywhere. Their omnipresence, ability to record climate change and map hidden resources make them more relevant than ever. These natural dossiers build an archive of the climates that have existed over a vast expanse of time and help manage the ecosystems of the future.

At the cutting edge

So what can we do after we predict the future? “You can decide where your resources go, into what aspect of ocean discovery and infrastructure development. Do we need to explore it? Do we need to exploit it? Or do we need to monitor it?”

She demonstrated one such execution at the Chilika Lagoon in Odisha. The lagoon in hindsight displayed no signs of trouble. However, when Panchang ventured into it, she could find only one species of foraminifera. “The lower the diversity of foraminifera, the more the stress,” she says.

She attributed metal pollution to heavy traffic of boats for tourism, aquaculture and the associated oil and fuel pollution.

A parallel investigation by an independent research group revealed metal pollution in the sediments of the lagoon, reinforcing her assessment. In ways like these, she connects the scientific tales of the past to the present to find what is often left out of the climate talks — the exploration of the root cause.

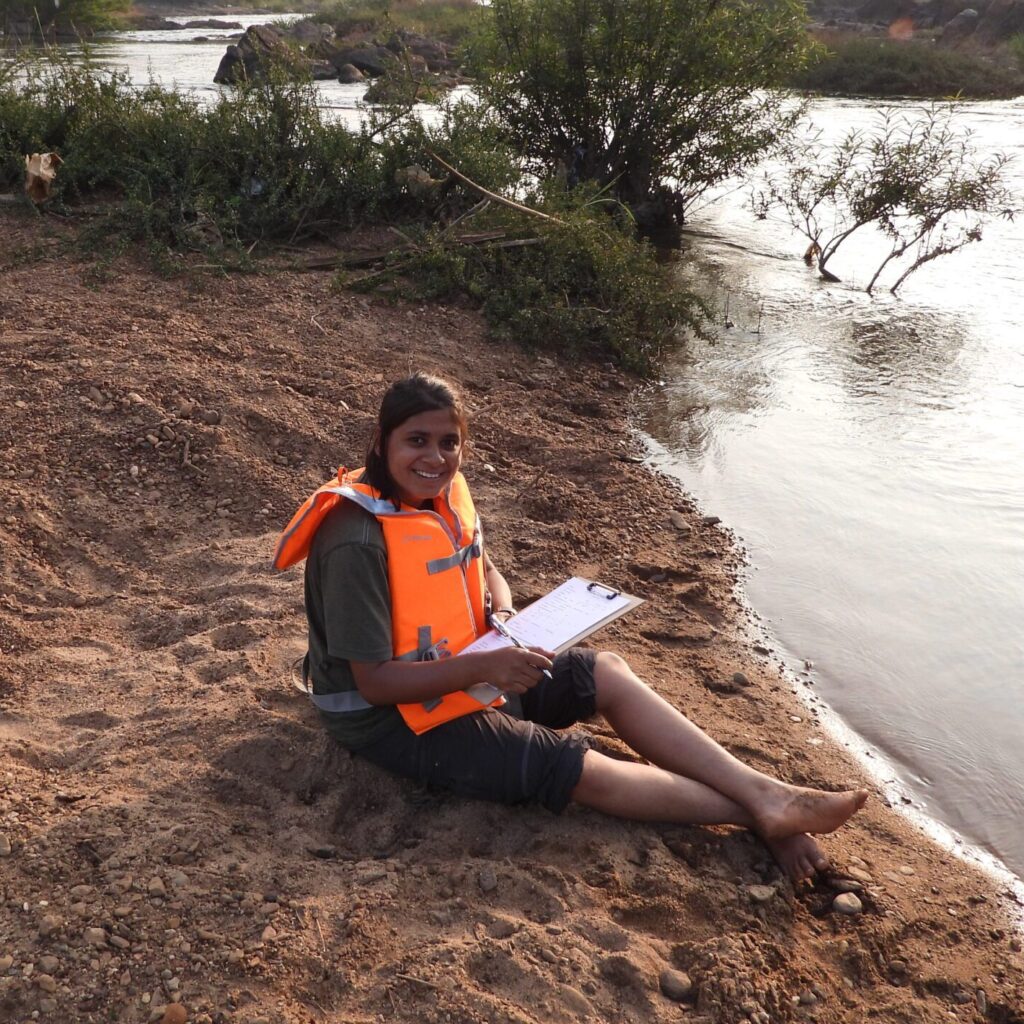

Preparing for the sub-sampling of a sediment core

Rajani came from a traditional South Indian family where men and their endeavours were given more precedence, her mother always fostered the ambitious trait in her. “My mother always told me that even if you choose to be a barber, be the best,” she says.

Panchang’s experiences shaped the path of her career. While pursuing her PhD, she noticed that all top jobs were served to men. Since the completion of her PhD from the micropalaeontology lab of NIO, only four more women have completed their PhDs under her research guide before he retired.

Following her PhD in 2008, she took a career break for two years to raise her daughter. She returned to her research endeavors as a Principal Investigator at the Agharkar Research Institute under the Women Scientist Scheme, where she investigated the possibilities of palaeoclimatic and environmental monitoring of estuaries along the west coast of Maharashtra using foraminifera.

A path of her own

Between 2014 and 2018, she was invited to teach courses in marine geology and oceanography, and sedimentology and sequence stratigraphy at Fergusson College, Pune. At the same time, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Pune, launched its Earth and Climate Science Department, where Panchang was invited to teach evolutionary palaeobiology as a visiting faculty.

In 2015, Panchang was awarded the DST Fast Track Scientist Start-Up Research Grant to work on human-climate interactions, which she pursued at IISER.

Meanwhile, a UGC Faculty Recharge Programme launched in 2011 inviting researchers to join teaching roles to bridge the gap between university-level education and research experience caught her attention. She joined it at SPPU in 2018 and established her own Marine Bio-geo Research Lab for Climate & Environment (MBReCE).

Since then, she has been expanding her research with the help of different grants from UGC, DST and Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES). “I know that if I am not self-sufficient, I will not be able to create opportunities for the future generation,” she adds.

Over the last five years, Panchang received two grants from MoES. One was to explore mechanisms and periodicity of ocean acidification in the Arabian Sea over the past 30,000 years, and the other to understand the sea level fluctuations over the past 14,000 to 10,000 years that shaped the formation of the Mahanadi Delta along the Odisha coast.

“While studying ocean acidification, I have been able to identify the first and most explicit record of the Holocene Climate Optima from the Arabian Sea [Ambokar et al, 2022, 2023]. Mugdha Ambokar and I have reported certain pteropod taxa for the first time from the off-Saurashtra region, and have validated that they have a biological sensitivity to changes in water temperatures rather than water depths [as considered before].”

She simultaneously mentors and prepares the future generations of women in science. “I do not know why I am a female magnet! I have three PhD students, all girls,” she quips. Following her path, one of her senior fellows, Mugdha Ambokar, will become the only trained pteropod taxonomist in the country after her. She is set to complete her PhD next year.

Ambokar started working with Panchang seven years ago. “I do not know many women scientists who have accomplished as much as she has. As a woman, I feel that you need that inspiration in your life. She is the push you need. Whenever you are tired and you do not know where you are going in life, Dr Rajani says, ‘Let’s aim for the moon so you can fall amongst the stars.’”

Constructing coring platform at sea

About the author

Kanishka Puri is a writer, photographer and up-and-coming documentary filmmaker. Her photo story titled ‘Reclamation by the Sea’, about the first women lifeguards of Goa, was awarded the Honourable Mention in MMEG’s second annual photo competition in 2022. She is committed to shaping narratives of intersectionality focused on gender.

Also By Kanishka Puri

Meet the turtle woman on the banks of Chandragiri

By Kanishka Puri

Ayushi Jain has developed a network of local conservationists of critically endangered Cantor’s giant softshell turtle in Kerala’s Kasaragod district