A portrait of a scientist, as an administrator

Dr Jyotsna Dhawan’s career spanning close to three decades is not just about tackling scientific questions related to stem cells. It is also about dealing with institutional structures, working for institution’s sustenance, and going about with the routine management tasks.

By Bharti Dharapuram

| Posted on March 6, 2025

Being a scientist starts with finding interesting questions to answer, planning and executing research, and teaching and mentoring students. But it does not end there. A scientific institution is a microcosm shaped by a community of people interacting with each other to identify a common vision and chalking out ways to realise it. However, the institution, being embedded within the larger fabric of society, is not immune to societal issues. Tackling them requires significant time and effort from the academic community, but this aspect of a scientist’s work is often hidden in the shadows.

Dr Jyotsna Dhawan (65) has straddled the worlds of a scientist and an administrator in a career spanning close to three decades. She is on her way to retirement after leading her research group at the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), Hyderabad, where her career began. Along with her students, she studied how muscle stem cells are maintained in a quiet state in our body to be called into action during repair and regeneration, which has important implications for disease and therapy. Beyond research, she has also been into various administrative and leadership roles.

Dhawan was among the scientists who envisioned the Institute of Stem Cell Science and Regenerative Medicine (inStem) in Bengaluru. She also helmed it for several years. She has served as a member of several grant and scientific committees and advisory boards, besides heading scientific societies.

Jyotsna studies how muscle stem cells in our body are maintained in a quiet state to be called into action during repair and regeneration. She is “happiest when dancing with cells” in the lab

Jyotsna’s first set of colleagues at CCMB Hyderabad in 2000

If you want something done, ask a busy person

“When you are looking for a faculty position, you are really looking at it as a scientist,” Dhawan says. Arriving with an eagerness to dive into science and in the absence of any formal administrative training, it takes time to appreciate aspects of institutional sustenance and regeneration. “In effect, well-thought out and inclusive institutional structures should support and enable scientific work, but sadly, that is often not the case,” she adds.

Administrative duties of researchers include planning and decision-making related to student admissions, new faculty search efforts, staff appointments and promotions, scheduling coursework, maintaining institutional facilities, making purchases and allocation of resources. All of these need to be done, tailoring the institute’s perspective to the larger expectations of funding agencies, while also maintaining a culture of openness and competitiveness in the field. These responsibilities are a huge burden, especially for young faculty beginning their research career, admits Dhawan.

Jyotsna lab group in 2007

“Some aspects are particularly onerous because they require sitting in judgement of your colleagues,” she says. It can be very distasteful when they fall in the realm of sexual or workplace misconduct. “But one cannot shy away from them, you have to participate sincerely because it strengthens the institutional mechanisms for dealing with a complex, and sometimes demoralising, work environment.”

Young faculty often have a visceral negative reaction to these demands on time, but it is important to take that energy and convert it into something that addresses the issue. Time plays an important role in teaching the ropes of the job. “Efficiency comes simply by the practice of doing things with as much engagement as you can muster. It does not mean that you will always do the best job, but you do a number of different tasks and do them in a timely manner… If you find yourself putting the best effort on everything you do, you burn out pretty quickly,” she says.

“There is a saying that if you want something done, ask a busy person,” says Dhawan. And it could not be more true for a scientist. “If you ask a working scientist what they did this morning, they will tell you they signed off on documents, dealt with a committee, edited a research abstract, got funding for a student to attend a conference, met with a colleague, responded to email, listened to complaints, multiple different things. All these, while trying to keep your research front and centre. Each of these, even if some of them sound trivial at first, requires a conscious thought process and engagement,” she emphasises.

Jyotsna Dhawan at the foundation of inStem in 2009 with Prithivraj Chavan, Minister of Science & Technology

Jyotsna’s lab group in 2011

All of these happen in the background of academic research and its many demands. Thinking about research needs space and enough room for creativity. “A cluttered mind cannot focus on research questions. Ideas come incrementally, in bursts, and it requires an openness of the mind,” she says.

Gender sensitivity is not just about women

“As a scientist, the difficulties of getting a lab off the ground are so enormous that you are not specifically thinking about encountering issues related to gender,” Dhawan says. “When I joined CCMB, there were several academically-accomplished women faculty members, but still a small minority compared to what one might want. That number, unfortunately, has not changed dramatically over the years,” she points out. “In any academic committee or meeting, you are very often the only woman and you get used to it.”

“We live in a social milieu and some of these issues are much larger, and not just limited to women in science,” Dhawan explains. “It is about how we ensure equitable access, opportunity, and working experience for people with differences — gender being the largest one of them,” she says. “As solutions, I feel there is a greater deal of complexity than we have focused on. There is also a substantial resistance to having open conversations about a supporting environment for inclusiveness as that is always interpreted as somehow lowering the bar, reducing competitiveness and merit.”

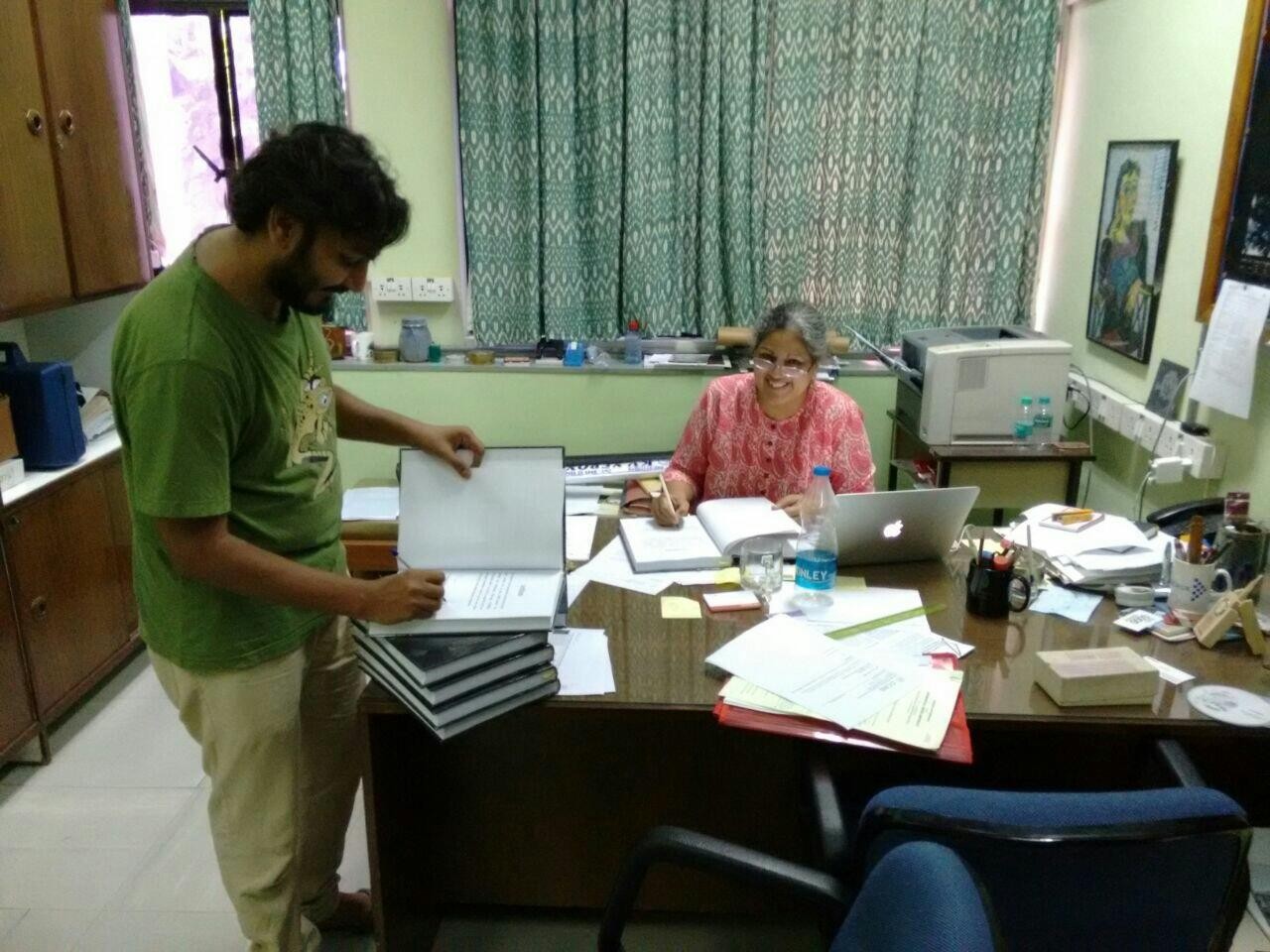

The long road to PhD thesis; Jyotsna signing her student’s thesis in her CCMB office in 2015

Nevertheless, she has seen some positive changes in the course of her career. “There is now better formalism for understanding the role of gender.” These formal structures, such as Vishaka guidelines, to deal with workplace sexual harassment have allowed women to openly raise issues that otherwise would have been difficult. But apart from focusing on a breach of women’s rights, she also feels “we need structures that do not see people through the lens of gender and promote broader inclusion of historically marginalised groups”.

“Most of the programmes associated with gender issues tend to be focused on female audiences,. But women already know this,” Dhawan says, while advocating for a more open discussion. She feels gender sensitivity programmes are one way to do this at academic institutions. “We need to have these programmes done by professionals where there is a space for conversations about women’s self-determination,” she says, adding that she would love to see her male colleagues actively participate in conversations about women in science.

The new set of colleagues at Jyotsna’s lab in 2018

Jyotsna Dhawan presenting her group’s research at a scientific conference in 2019

“Every March 8, we have these programmes where a prominent woman scientist is invited to speak to a group of women scientists — a real case of preaching to the choir. Women in science have already experienced these challenges.” Instead, Dhawan suggests that she would like to see male colleagues as speakers, and more importantly as the audience, taking an active lead in engaging with the challenges.

Pointing out how regulatory guidelines for research are adhered to, but are not mandated for gender sensitivity, she remarks, “If all institutes can enforce regulatory procedures to perform certain [science] experiments, it is definitely possible to mandate everyone to attend a simple yearly awareness programme and engage in a conversation about gender.”

There is a lack of interest in fostering such programmes from being strapped for time, and “a feeling that addressing them distracts us from doing science”. “But we do it to our peril, and it leads to a build-up of issues,” she notes.

Scientific institutions are a part of a complex sociological system and the solutions are not going to be simple or straightforward. “Everyone feels we know the path because we can all see quite clearly the unremedied problems that we face. But I think it requires acknowledgement and engagement with a larger set of things.”

“That larger context is an appreciation of institutional culture: what are the things that you as a scientist find enabling in your environment and what are the things needing change we need to collectively work on. These are not things that can come from administrative fiat — they require honesty, openness and nonpartisan discussions and the ability to see colleagues as fellow travellers and not as competitors for institutional resources.”

About the author

Bharti Dharapuram is an ecologist with a PhD from the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore where she studied how ocean currents and environment shape coastal biodiversity. Following this, she studied arthropod diversity in the forests of the Western Ghats for her postdoctoral research at the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad. She has been drawn to language and writing since childhood, which led her to the annual Science Journalism course offered by the National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bangalore. During the challenging phases of her PhD research, she found solace and fulfilment in writing about scientific discoveries and the people behind them.

Add a Comment