Sticks and stones may break my bones but...

Bhopal: Debjani Raychaudhuri (37) survived a hostage-like situation in the forests along the Bihar-Jharkhand border in 2014 after an encounter with Naxals. Though she is scholar and not a soldier, the incident is typical of the many adventures she has had while Mapping landforms and studying meteorites for the Geological Survey of India (GSI).

A senior geologist in GSI’s Meteorite & Planetary Science Division, Raychaudhuri could have opted for a cushy office job after she cracked the UPSC Geologists’ exam in 2008 and got a posting in Bharat Petroleum, but she chose to be in the field and got herself transferred to GSI. Along the way, she has broken many stereotypes around women in geology.

Being a woman in STEM, she said it is only in the professional world that she has become conscious of being a “lady geologist”.

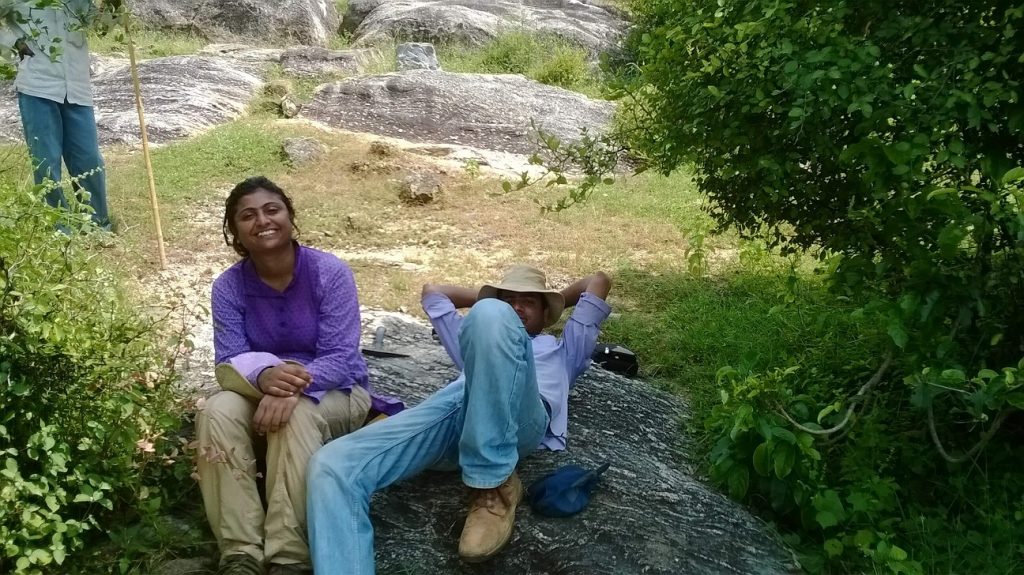

The job has taken the graduate from Jogamaya Devi College, Kolkata, to the remotest corners of the country. While many women shy from fieldwork because of physical exertion and unfavourable circumstances, Raychaudhuri said if women want, they can move mountains, or even better, map them.

It is true though that during her encounter with Naxals, she feared for her safety and dignity. “My field partner Aditya and I were traversing through one of the jungles near the Bihar-Jharkhand border when we ran into them. There were many of them, armed with guns. As a woman, I was worried about them misbehaving with me. We were made to sit till it was dark,” she recalled.

She did not tell her family about the incident until her field visit was over, so they would not get worried. But when she eventually told them, they couldn’t help but marvel at her bravery and her ability to deal with such a challenging situation,” said Debasree Raychowdhuri, her elder sister, a banker.

Even today, their parents’ blood sugar shoots up during field visit seasons, according to Raychaudhuri.

Raychaudhuri said the Naxals checked their maps, GPS and compasses, and even their vehicle to see if they were from the administration. “But once they got the assurance that we were not from the government, they left us at the same spot from where they took us. They said: ‘Lijiye, madam, jaha se legaye thay vahi chhod kay jaa rahe hain; bahar ja ke badnaam mat keejiyega (We are dropping you at the same place from where we picked you. Don’t defame us once you leave),” she said.

She said they did not face any problems from the Naxals thereafter. “Had they objected, we would not have been able to complete the assignment. They allowed us into the remotest parts of the forest. For the next many days, we knew exactly where we would find them, but we also knew they wouldn’t stop us,” added Raychaudhuri.

Jumping across foxholes

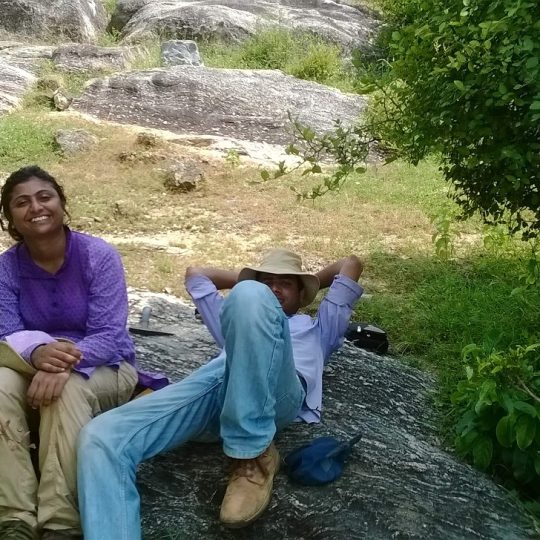

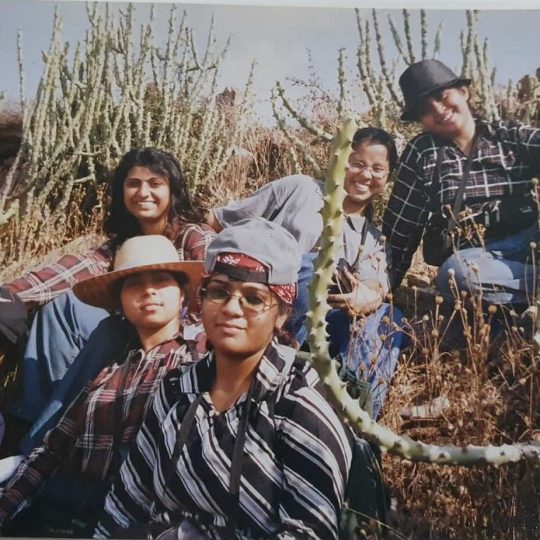

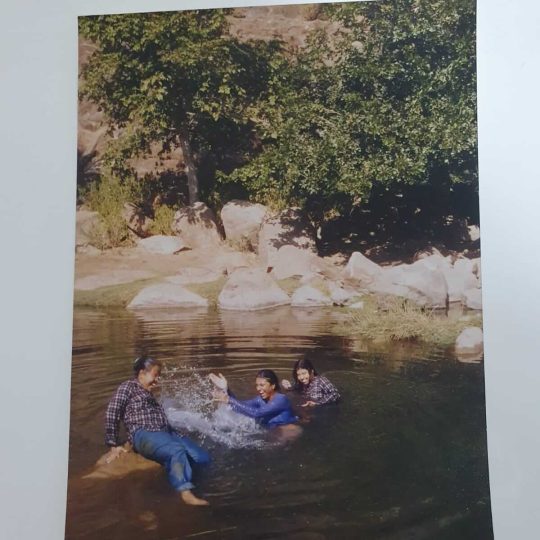

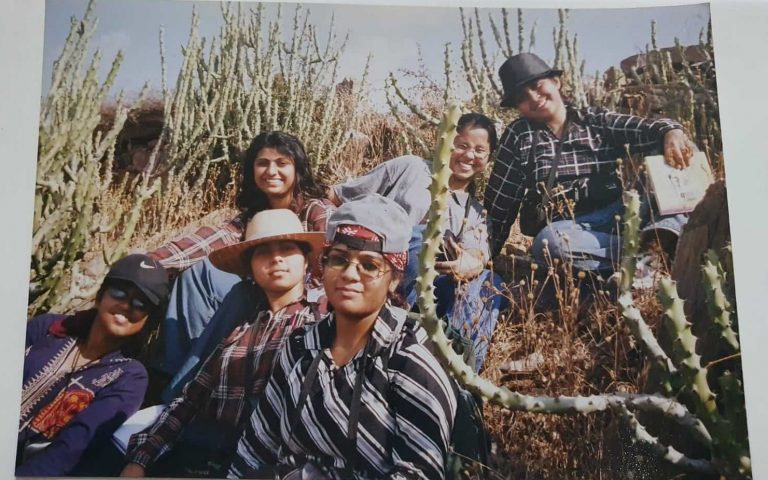

Debjani Raychaudhury and her friends on a field trip while in Jogamaya Devi College

Debjani said she realised that it was a little unusual to be a woman geologist on the field, but she had not been so conscious about her gender at home or in college.

I studied in an all-girls college and grew up in Kolkata. I had actually never had the feeling that there were fields that were male-dominated or female-dominated,” she said

From early on, she was thinking on her feet and taking risks. The GSI officer’s classmate from college, Diya Arora, recalled an incident from when they were young. “In our second year of college, I lost a clinometer (an instrument used for measuring angles of a slope) during a field visit to Rajasthan. Debjani and I went looking for it after dark. We got lost and struggled through rough brambles and bushes. We finally saw our campsite across the highway. To get to the other side of the barricaded highway, we jumped into a foxhole and climbed out on the other side. It was risky, but it is a memory for life,” said Arora, a petrologist with US-headquartered multinational company Emerson Automation Solution.

Raychaudhuri’s father gave that gentle nudge his daughter needed to quit the desk job for fieldwork. Durgadas Raychaudhuri, an 80-year-old retired mechanical engineer, said he asked Debjani to work in GSI because she did not study geology to sit in an AC chamber. “I do not think there is anything that girls cannot do. As she is a sportsperson, runs marathons and is good at handling tough situations, I had complete faith in her: if she is on the field, she will do wonders,” he said.

Love for science

Raychaudhuri’s first love continues to be science as she feels every meteorite is unique. At present, she is studying an iron meteorite, which forms the core of an asteroid, retrieved from Jalore in Rajasthan. “Meteorites hold secrets to the universe. Chondrites are the most commonly found meteorites and hold information about the elements of the universe. Carbonaceous meteorites are said to have brought life on earth. They have minerals and hold proof of there being water in space,” she said.

Her parents worry, but they stand by her decisions. “When she would go on field visits in college, we used to talk to her twice a day to ensure she had reached camp safely. Even today, our parents worry about her. For them, she will never be a ‘senior geologist’ ; she will always be their younger daughter,” said Debashree.

Raychaudhuri said fieldwork has removed the atypical image she earlier attached with the life of a government officer.

Need for persistent education and inclusion

You are out of your comfort zone and there is no luxury,” she said. She has had a brush with casteism too. “At the places where we take up field assignments, we rent houses for six months and so on. The first question most homeowners ask is: ‘Kaun jati ke hai aap (which caste do you belong to)?’ This is the case even if you show them a government-issued ID card,” she said.

As a lot of the work involves travelling to remote corners of the country, the job is unpredictable. “On the field, you suddenly see yourself walking kilometres after kilometres, across bushy and thorny paths, in semi-jungles and hillocks, paddy fields and shallow streams. Your vehicle gets stuck and you end up pushing it with your teammates. In worse cases, you walk again to look for a tractor that could tow your vehicle,” she laughed.

Being a woman in the field

For a woman, the challenges are tougher. As there are no toilets on the field, women researchers have to wait to get back to the camp if they have to relieve themselves. She said it is a major factor that deters women from opting for fieldwork. “You can imagine how difficult things can get when you are working and have no place to relieve yourself. The most common solution is to answer nature’s call in nature, but it is not convenient for me and most women. It is also not healthy to hold it back for 8-10 hours,” said Raychaudhuri.

She feels field vehicles should be equipped with portable toilets to ease the life of woman geologists. “Temporary portable toilets could make a big difference. Since every field party is associated with a vehicle, we need a solution like this,” she said.

Initially, there were many projects that were considered too tough for Raychaudhuri as she is a woman. “These challenges were there, are there and will be there,” she said. “But then, you also have some great male colleagues who fight for you and your case, and who trust you with difficult projects. So, it depends upon your past performance and experience. I can safely say hard work pays.”

She feels fieldwork keeps many women away from geology. “Geology encompasses different streams. The ones that are field-centric perhaps deter women because it involves hard work, long periods away from home, and hardships on the field. Given a chance, not only women, but also men would prefer a life of comfort. Perhaps, this is why you do not hear many people opting for geology as a profession,” she said.

Debjani feels the job goes beyond science.

“If your health and family permit, go for assignments even if they are in rough terrain. You will learn geology, but also how to live more.”