Empathetic ears on the ground: What it takes to do ethical research

Two scholars explain how fieldwork is not just about collecting data but about listening, representing, and giving back.

By Yams Srikanth

| Posted on September 23, 2025

“Studying ‘agri-cultures’… brought home to me the sharp variations in rural worlds as I was brought up in a coffee plantation which was vastly different from this agrarian world,” said Dr Aninhalli R Vasavi, describing her first experiences with prolonged, immersive fieldwork. She uses the term “agri-cultures” to describe the complex ways agrarian communities relate to land, nature, and livelihoods.

Vasavi began her career as a social anthropologist and has since researched sociology, agrarian studies, and education. She is also an awardee of the 2013 Infosys Prize. Her research spans geographies and disciplines, but one constant has been her emphasis on fieldwork. Between 1990 and mid-1991, she lived in Madbhavi, a village in Karnataka’s Bijapur district, where she studied how people responded to drought and cultivated resilience. More than three decades later, she continues to visit Madbhavi to document new trends. Today, she also works with agrarian communities through PUNARCHITH (“re-think”), a collective based in Chamarajanagar district that develops alternative ideas for rural India.

Dr Tamma and Meren conducting a bird count

“This was a particularly formative experience for me as it highlighted the need to develop a deeply empathetic and culturally nuanced approach to fieldwork,” she explains. Prolonged engagement, she adds, revealed the community’s rich knowledge systems and skills, insights that would have been invisible to a short-term observer.

“Fieldwork, and fieldwork over long periods of time, is absolutely essential,” Vasavi stresses.

Rethinking ‘field’

At first glance, the “field” seems simple: somewhere beyond home, where a researcher collects data. But Vasavi challenges this view. “A ‘field’ is a context which researchers have to relate to, understand, study, learn from, and represent. It is also a site for reflexivity, to re-think and consider what one may have read or studied in the abstract… The ‘field’ is a key site where not only life-worlds are studied and represented but where ideas, voices, and agencies of the people from those ‘field sites’ are to be represented by us as researchers.”

This responsibility, how researchers choose to engage with and represent the communities they study, is central to her work. Between 1999 and 2001, Vasavi led a study across five Indian states: Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttarakhand to understand exclusion in elementary schools. Her team wanted to capture the “cultures of institutions” like education departments.

“In our study of school teachers, we had to make a special effort to get Dalit teachers to be interviewed and to be part of the study. This could be done not only in the school (where they were mostly intimidated) but we had to visit them at their homes and get them to speak to us in conditions of anonymity and assure them confidentiality,” Vasavi shared.

Making research inclusive, she argued, is not optional. “Every researcher bears an onus to make the field or site of study more inclusive. In a hierarchical and extremely unequal and gendered society such as ours, many are often invisibilised. Attempting to ensure that the voice, agency, and presence of all are included is a must for any field research to be authentic.”

Dr Tamma and her team explore a coffee plantation

Insider versus outsider

Vasavi added that “the field starts at home,” but both she and Dr Krishnapriya Tamma, an ecologist and associate professor at Azim Premji University, have often studied communities they are not directly part of. For Priya, who grew up in Bengaluru but works in Northeast India, the question of insider versus outsider is inescapable.

“The turning point for me came during my PhD fieldwork,” she said. “I was working in Arunachal with someone my age, but he was helping me with my work. It struck me with great violence that the only reason we were in our respective positions was education. I had access to resources that he didn’t. The one difference between us was the difference in opportunity… And yet, if we were both asked to explain our stand in conservation, mine would perhaps be taken more seriously.”

This recognition shaped how she approached her research on shifting cultivation, or jhum. “For someone unfamiliar, it can look terrible…the cutting and burning of forests to grow crops. When I first came, I thought jhum was not ecologically sound. But as a system that developed in hilly regions, it is adapted to the conditions and is deeply tied to cultural and religious systems across the Northeast. If managed well, it can also provide important biodiversity conservation services.”

Her perspective evolved only through long-term engagement. Without that sensitivity, she warns, research and policies could easily misrepresent jhum as destructive, sidelining the communities who practice it. “Who gets to make rules about how people can access lands they depend on? Where do the ‘lines of stakeholder-ness’ extend? Why should my ideas of conservation be more important than those of a resident of these landscapes? These are very blurred lines.”

Recognising hierarchies is equally vital. “It’s vital to recognise that communities are not homogeneous,” Priya stresses.

Vasavi has seen this firsthand through PUNARCHITH. In Chamarajanagar, wealthier farmers who profit from hybrid seeds, chemical inputs, and tube-wells often set the model of “success.” Smaller farmers, in trying to emulate them, fall into debt. Promoting sustainable agriculture has been difficult, she admits, because of these entrenched inequalities and aspirations. “The hegemony and internalisation of the dominant model pose challenges for us to make alternative models possible,” she says.

“Ethics requires prolonged engagement,” Dr Vasavi stresses

The model of ethics

Both scholars insist that ethical fieldwork cannot be rushed. “The quality of research from long-term studies is just unbelievable,” Vasavi says. But institutional pressures, from funders demanding deliverables to universities pushing quick publications, rarely allow that depth. “Ethics requires prolonged engagement,” she stresses. “Understanding how you relate to your field, and your own place within it, is vital.”

Ethical research also requires giving back. Both Vasavi and Priya emphasise the importance of sharing findings with communities, not just peers.

Dr Vasavi at a meeting on farm women’s rights in 2023

“Scientific papers are meant for peer-sharing, so they do not work as a means of sharing information with communities we work with,” Priya notes. Her team submits reports to village councils, holds discussions, and has even created a bird field guide in the local dialect.

“At PUNARCHITH, we attempt to share all the information and knowledge we have gathered from the community with the members themselves. We conduct discussion sessions, street plays, interaction sessions, and awareness drives. More recently, we’ve used WhatsApp to share updates,” says Vasavi.

Both also highlight capacity building: from PUNARCHITH’s Panch Payana program for rural women, to CREST in Kozhikode, which trains students from disadvantaged caste groups. For Priya, it is about mentorship. “A person from the community I work in in Nagaland might not do the work as quickly, at first, as someone from an urban background. That’s not because they’re less capable, but because of a lack of opportunity and training.”

Letting go

Rarely are those most affected by conservation or agrarian decisions the ones making them. While grassroots grants are emerging, barriers like language remain. Until institutions shift, the imbalance persists.

“In a country like India, research can’t keep pace with how fast things are changing on the ground. You need to have your ear to the ground, and you can’t do that without fieldwork,” Vasavi says.

At its heart, fieldwork is about relationships between researchers and communities, institutions and funders, insiders and outsiders, and even within communities themselves. Ethical fieldwork demands patience, reciprocity, and humility.

Perhaps, as Vasavi and Priya suggest in different ways, it also demands letting go of the idea that knowledge and power can belong to a select few.

Dr Tamma and her team in Nagaland

About the author

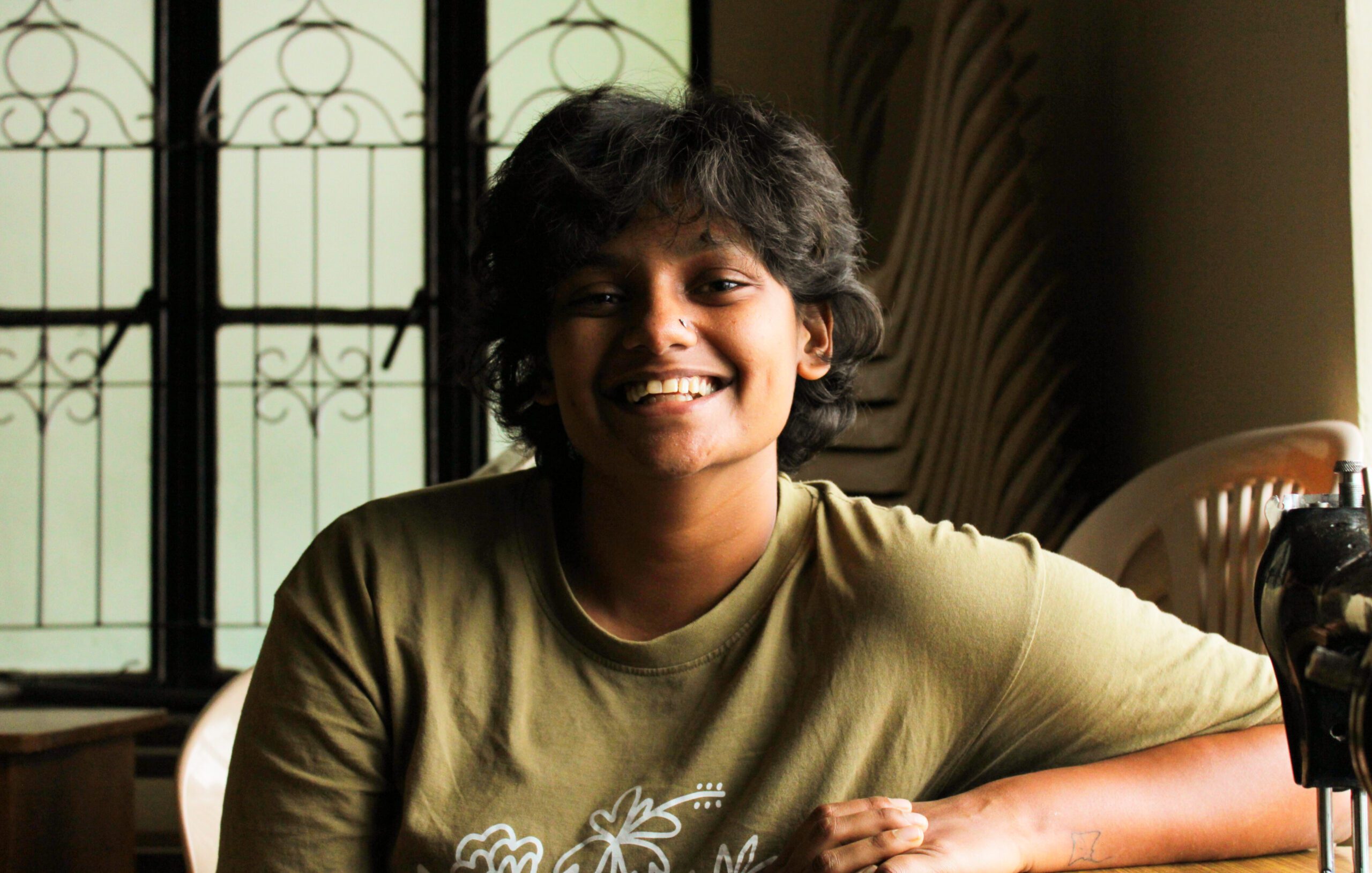

Yams Srikanth is an ecologist whose other interests include science communication, writing and trying to build a better world. When not languishing in front of their laptop, they can be found outside poking at any insect, bird or plant. Their undergraduate degree in Biology and Education, along with a Master’s in Wildlife Biology has given them skills and perspective to help readers appreciate and handle the environmental issues of the Anthropocene. They also write about queer and trans rights and their intersections with STEM and education.

Add a Comment