Catch ‘em young: why early impressions of science matter

There is a gender gap in choosing science, with girls more likely to opt for non-STEM streams after class 10 — an idea shaped partly by wrong perception of one’s ability, lack of women role models and biased classroom interactions of teachers

By Yams Srikanth

| Posted on January 7, 2025

When was the last time you studied science in a classroom? Perhaps in university if you had pursued STEM, or in class 10. Regardless of when you did, teachers, curriculum and role models you interacted with when you were young have undoubtedly shaped your current feelings towards science.

For girls, this is doubly true. Attitudes, perceptions and self-confidence about capability to do science are shaped by their experiences in school. In textbooks of Punjab, Pakistan, researchers found that women were depicted in caregiving roles of teachers, nurses, etc. In contrast, depictions of men included engineers and scientists. India’s NCERT textbooks published as recently as 2022 present a similar disparity. Just 34% of gendered words (he or she) are female, with an overwhelming 66% being male.

There is a gender gap in choosing science, and this choice shapes the future of girls. An individual’s subsequent course of study and the nature of jobs available depend on the stream chosen at the school level. Female teachers often internalise ideas of capabilities surrounding spatial problem-solving and math, doubting both themselves and their female students.

Data demonstrates that women who choose STEM or commerce stream are more likely to participate in the labour force, secure salaried employment, gain higher earnings and choose a male-dominated occupation. Success in the labour market in turn leads to a household reduction in gender gaps and better treatment for women. The gender gap is also significantly reduced when there is a greater educational parity between parents. Hence, it is important to engage girls in STEM because it is the right thing to do. Adequate representation of marginalised groups is a moral imperative.

Science Gallery Bengaluru conducts many programmes for students and young adults and in their experience ‘girls love STEM, but rarely get opportunities to engage with it.’

Non-formal educational spaces

Although school is the most crucial driver in improving women’s participation in STEM, it is not the only one. Learning environments outside of schools and universities can often be powerful tools in shaping early interest in STEM. These could include community centres, libraries, museums or makers’ spaces. Research from Uzbekistan suggests even TV shows and documentaries as spaces where girls become engaged in STEM. When the work of a female scientist or researcher is featured, the content is particularly impactful.

Science Gallery Bengaluru is a not-for-profit public institution that aims at engaging young adults in the human and natural sciences, engineering, art and design. In addition to their public gallery space, they conduct workshops and long-term learning programmes.

Science Gallery often hosts schools, both co-ed and single gender. Although a roughly equal number of girls and boys visit, gallery’s programme and learning manager Vasudha Malani recounts her anecdotal experiences during school visits.

“The girls take up less space when we do walk-throughs with them. They tend to be around the sides of the exhibit, with the boys in front and centre engaging with the mediators. We do try to get girls to speak out and engage more, though,” Malani says.

This shows that even outside of school, girls are socialised out of engaging with STEM despite an innate interest. In learning programmes, however, the situation is quite different. These take place in smaller groups, with more intimate discussions and sharing. Science Gallery also conducts long-term engagements through their Mediator and Summer School programmes.

“There are more girls than boys who apply and sign up. I would say they are pretty involved in the activities. Lots of women outside of STEM also sign up for these workshops,” Malani comments.

In the absence of long-term data, the overall benefits are unclear. Nonetheless, their success in involving girls despite existing disparities in STEM participation highlights something that is apparent — girls love STEM, but rarely get opportunities to engage with it.

Spotlight on women in STEM

Our hopes, dreams, views and attitudes are inextricably linked to our experiences and contexts. Young girls who never see themselves represented in the fields of science and engineering rarely dream of it as a possibility. Research led by UNESCO in Asia demonstrates that the visibility of female STEM researchers positively impacts interest and confidence of girls across urban and rural contexts.

Role model exposure had a positive impact on the sense of belonging for undergraduate STEM students. Role models work even more effectively when they are similar to students in socioeconomic background and identity. When girls in primary and secondary schools interact with female mathematicians, they are even more likely to enjoy math, attach more importance to it, and have greater faith that they would succeed.

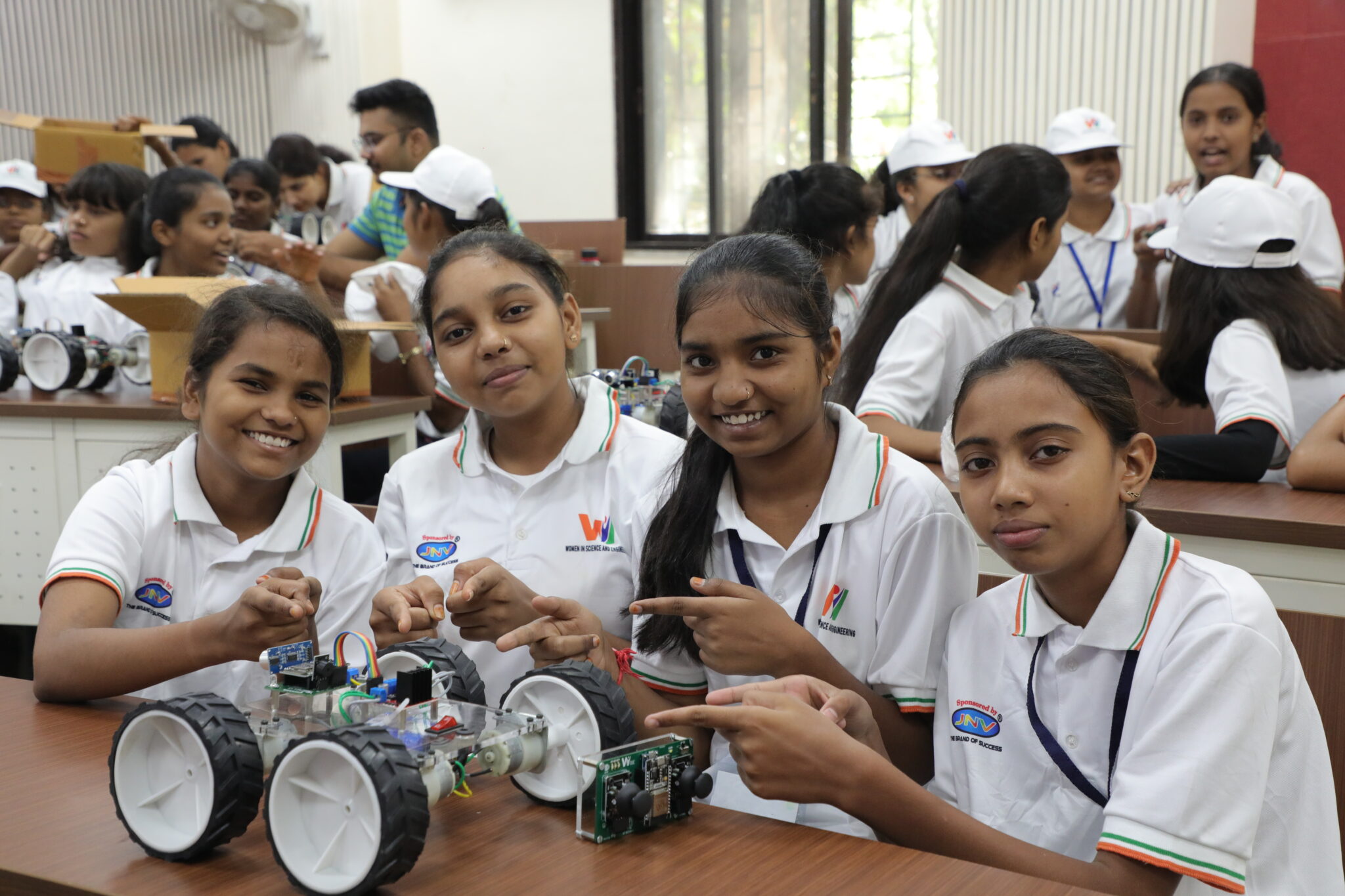

IIT Bombay’s Women in Science and Engineering (WiSE) programme, initiated by Professor Rajesh Zele and sponsored by IEEE CAS, is designed to provide role models for girls from rural parts of India and encourage their pursuit of STEM fields. Under Professor Zele’s leadership, the 2023 and 2024 editions of the programme welcomed 320 girls from rural backgrounds across Maharashtra, Odisha, Bihar, Gujarat, Goa, and Daman and Diu to spend a week at IIT Bombay.

Participants were specifically selected from schools in rural areas of India. The programme is strategically timed for students entering class 10, a crucial period when they choose their academic streams. During their time at IIT Bombay, these girls engaged with volunteers and mentors to explore potential career paths.

WiSE programme coordinator Arti Auti explains the need to ignite the curiosity of girl students. “They are eager to understand how things work. We aim to include elements from their everyday experiences, along with unique activities such as examining drones and submarine vehicles, radio-to-light bulb projects, and even building rovers. They particularly enjoy the hands-on activities.”

Mediators engage visitors in hands-on experiments at Science Gallery Bengaluru

Activities such as disassembling and reassembling a mobile phone offer familiar yet intriguing challenges. These hands-on activities effectively engage the girls and help them feel comfortable with technology-oriented fields.

“On the first day, they are shy, but they will soon start participating, talking and asking questions. Their confidence grows exponentially,” Auti notes.

The programme includes discussions and interactive sessions with “Winspirers” — women working in STEM and related fields. Past Winspirers have included doctors, farmers, fighter pilots, researchers and activists.

“These women are not celebrities; they often come from humble backgrounds, making it easier for the girls to relate to them. We hold Q&A sessions where the girls can learn about their struggles and how they overcame them,” Auti highlights.

Role models provide a beacon of hope. Learning about available support systems and ways to overcome challenges can be crucial in engaging girls in STEM. The programme also encourages spreading STEM awareness within their communities, with support from accompanying women teachers. Additionally, IIT Bombay students act as long-term mentors, guiding these girls as they progress in their education.

Gender-sensitive pedagogies

A good teacher can be instrumental in shaping an interest in science. This is true for boys and girls. A teacher who engages in discussions and conducts experiments is far more likely to foster a long-term engagement with STEM than one who reads out from a textbook.

Anagh Purandare, a teacher at Azim Premji School, highlights that innate interest in STEM has little to do with gender, but girls are more likely to be socialised out of it. One driving factor is teachers.

“I have not observed gender playing any significant role in the classes I have taught. These include class 7 to 12 students in a private school with most children coming from privileged backgrounds. Typically, in my experience, there are students who are interested in science and others who are not, but they are not divided based on their gender,” says Purandare, showing how based on the relative proportions of men and women in STEM, it is easy to assume that women may simply be less interested.

Though there is a dearth of India-specific data on urban-rural divide in science-related gender gap, there is data from countries with similar contexts like China and the Asia-Pacific region.

Teachers are people, and people in positions of power. That means they come with their own unique set of biases and prejudices that are rarely left at the classroom door.

Classrooms need to be gender responsive, creating a learning environment where all genders feel safe to express themselves and participate. All students need to feel valued and involved in the teaching and learning process.

A WiSE workshop for girl’s to build their own robotic car

IIT Bombay’s Women in Science and Engineering (WiSE) programme is designed to provide role models for girls from rural parts of India and encourage their pursuit of STEM fields

Purandare suggests that the subject’s content can also play a role. “For historical reasons, very few non-male scientists and their contributions are included in the textbooks. Teachers can be more aware of this and should try to include more gender diverse examples and/or draw attention of the students to this gender bias while teaching,” he adds.

Moreover, teachers need to reflect on their actions. They should be aware of how their own attitudes can affect their teaching, and take steps to prevent discrimination in their classrooms. Gender equality needs to be a core aspect of language in classrooms, planned activities, and interactions with students. We also need to address implicit biases, such as those regarding girls’ abilities.

Take for example a female teacher who struggles at math. A gender-responsive teacher might highlight the challenge, while asserting that this has nothing to do with gender. A biased one may attribute it to gender, creating the same fear and anxiety of math failure in her girl students. A very skilled teacher may even draw on the diversity of students’ backgrounds and experiences to communicate concepts.

If a teacher is not interested in gender equality, no amount of sensitive pedagogy can create an inclusive classroom. All teacher training comes with a crucial caveat — teachers need to value diversity in learners, and be committed to supporting all learners.

It is also important for young girls to see themselves reflected in STEM fields. The visibility of women in STEM and the opportunity to interact with them can be invaluable in fostering a sense of belonging. Lastly, it is important to note that school is not the only venue for STEM education. Although it can be vital, a love for STEM can come from anywhere.

About the author

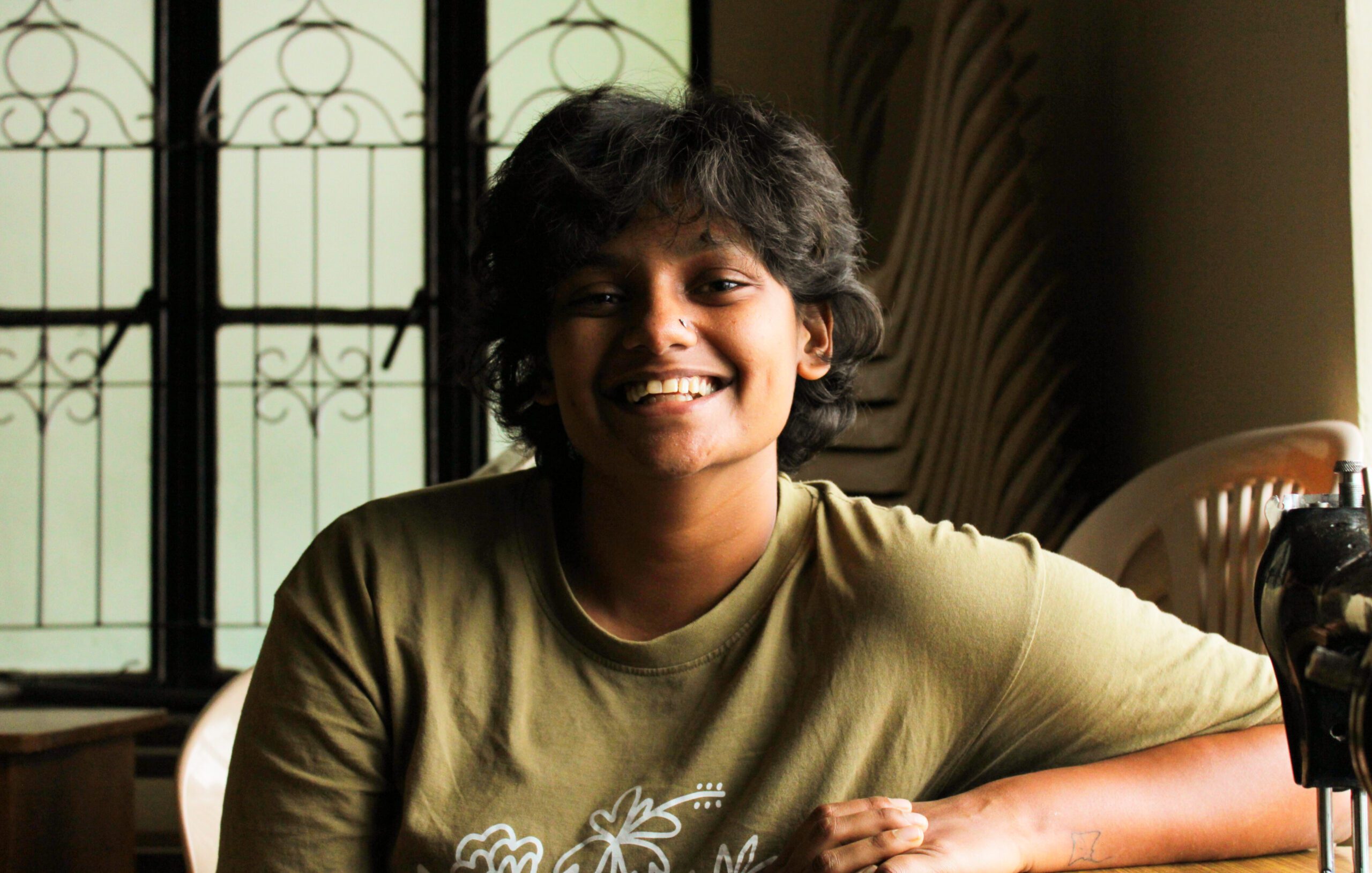

Yams Srikanth is an ecologist whose other interests include science communication, writing and trying to build a better world. When not languishing in front of their laptop, they can be found outside poking at any insect, bird or plant. Their undergraduate degree in Biology and Education, along with a Master’s in Wildlife Biology has given them skills and perspective to help readers appreciate and handle the environmental issues of the Anthropocene. They also write about queer and trans rights and their intersections with STEM and education.

Add a Comment