'For me, it was never an issue of what to do. Everything was fascinating'

Dr Renee Borges draws from chemistry, behaviour and ecology to interrogate how organisms perceive the world and make their decisions

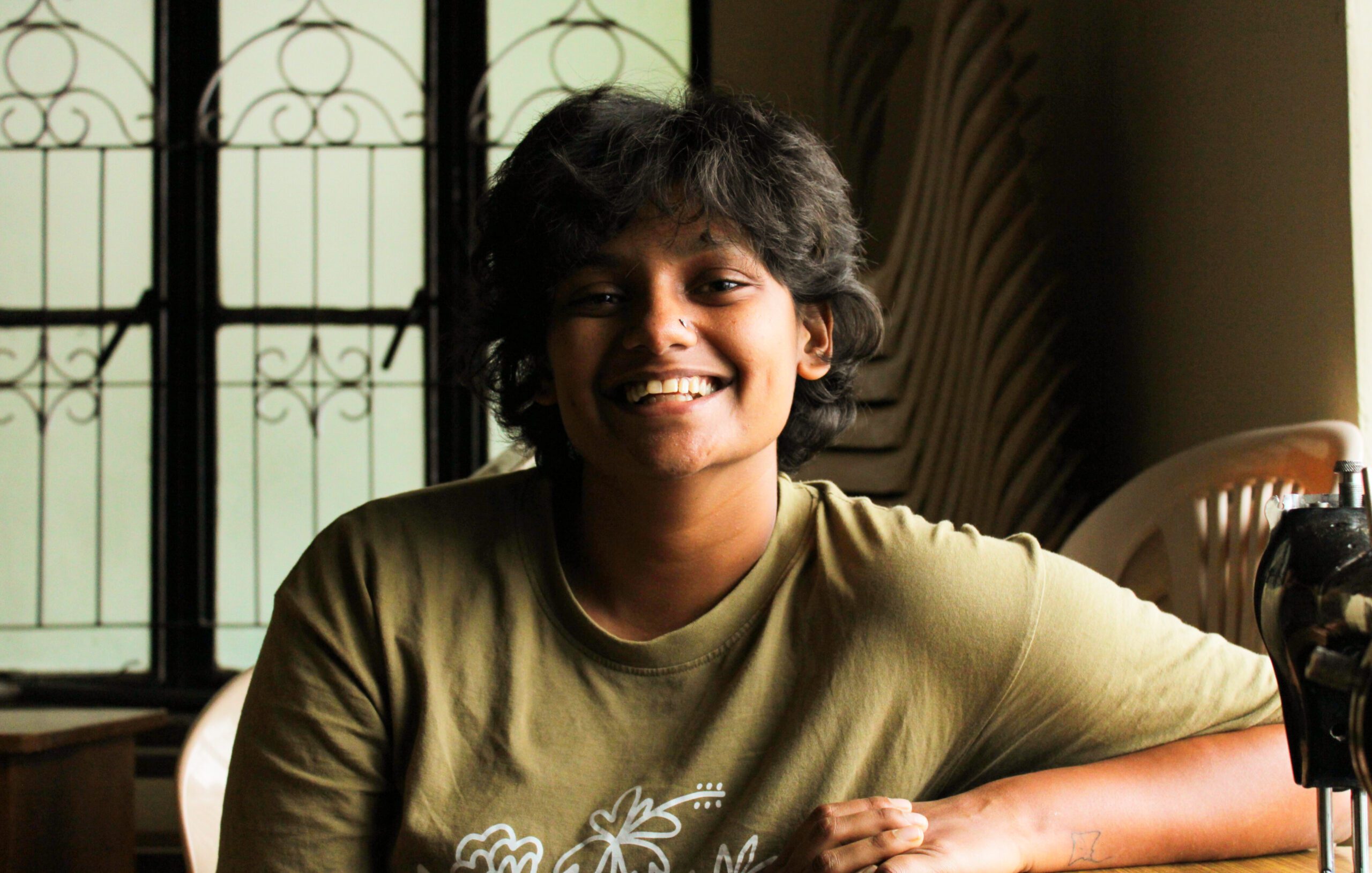

By Yams Srikanth

| Posted on February 27, 2025

The decades-long research of Dr Renee Borges (65) spans all creatures big and small — but mostly the small ones. Her study organisms range from the ancient Ficuses of the Western Ghats to termite hills on the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) campus, where she works as a Professor. Her research is all about understanding how organisms perceive and negotiate the world, and with whom they interact. She draws on chemistry, physics and even structural engineering to answer these questions.

Driven by a curiosity about nature’s interconnectedness, Borges made significant strides in understanding how species interactions evolve and adapt. Although she now answers fascinating evolutionary questions, she began with an innate desire to understand natural history. “For me, it was never an issue of what to do. Everything was fascinating,” she noted.

Much of her childhood and education in Mumbai was spent outside. She studied BSc Zoology and Microbiology at St Xavier’s College. She recounts exploring the Sanjay Gandhi National Park with classmates every Sunday, botanising and looking for birds. She also worked every evening at the Bombay Natural History Society with Dr Humayun Abdul Ali, curating the collections. She even had varied pets — scorpions to snakes — until her mother made her give them away.

She did MSc in Animal Physiology from the Institute of Science, University of Bombay. For her PhD at the University of Miami, she worked on the Malabar Giant Squirrel.

“Natural history is at the core of everything,” Borges stated. “Without that knowledge, none of the work I do would be possible… and I could not ever study just one thing for the rest of my life.”

A bird ringed by Srinivasans team in the Eastern Himalayas

Seeing through another’s eyes

“It was difficult working with the fungus-growing termites because it was a difficult study system to open up,” Borges noted.

Although termite mounds may seem like a simple pile of mud to the untrained eye, there is more to the mound than meets the eye. Termites are busy at work, gardening varieties of fungus. Contrary to popular opinion, termites do not eat wood themselves. They grow fungus that eats wood for them. Termites have to defend this fungus against other fungi that seek to parasitise the colony. With so many minute parts, it is no wonder that Borges’ team had trouble working the system.

“In order for the system to tell you what it is responding to, you need to do experiments,” Borges emphasised. “Smaller systems are more amenable to experimentation. And many of my systems are even around me on the campus. So we can use all the sophisticated tools we have.”

“To get a system to talk to you, you need to crack it. And that means thinking like an earthworm or an ant — getting down to that scale that is relevant. We have all the hardware and software to throw at a system, but we need that opening first,” Borges explained.

It is a powerful idea. So often, we centre the human experience in our work. When trying to understand termites, ants or fig wasps, the human experience is irrelevant. Borges’ team recently uncovered that male fig wasps do not have a sense of smell. Their entire life from birth to death takes place within one fig, meaning that taste is likely far more useful than smell. It feels like an alien concept. Navigate the world with tongue? That is why a fig wasp researcher needs to think like a fig wasp, and not a researcher.

In India, her most popular work has been about uncovering the relationship between figs and fig wasps. A very interesting paper of hers focuses on demonstrating the differences between very closely related bee species, one being nocturnal and the other being diurnal. Another compelling work focuses on how nocturnal bees are able to learn by starlight. She has also worked on how habitat loss can affect interactions between closely associated trees and insects.

Exploring interdisciplinarity

Borges’ skill of drawing from parallel disciplines began as early as her PhD. She studied the Malabar Giant Squirrel, trying to understand their food choices and behaviours. These furry creatures are herbivores nesting in treetops of the Western Ghats. The squirrels chose various fruits, stems, seeds and leaves. Borges analysed their food to figure out its chemical makeup and to learn whether that might be driving their choices. It is a field known as phytochemistry.

“I was always fascinated by chemistry… The more we look at biology through the lens of chemistry, the more insights we get,” Borges recalled.

Studying the root bridges in Meghalaya and the Fig Wasps that pollinate them

“My current fascination is potter wasps,” Borges adds. Potter wasps, also known as mud dauber wasps, are minute insects that create beautiful pot-like structures out of mud. They raise their larvae within these pots.

“I am working with an engineer to understand the structure and stability of their nests and to compare these to how termites build their mounds… I have learned quite a bit of physics and chemistry doing these things.”

Science is all about identifying your question, then using every tool and discipline you know to tackle that question. “In the campus, people are used to getting very strange phone calls from me,” Borges quipped, recalling a set of force-based experiments she did. “I think we should welcome barging into each other’s labs.”

For Borges, working alongside other scientists to tackle a problem is a regular occurrence. IISc also lends itself well to this practice, housing dozens of different disciplines between its Gulmohar trees.

Species relationships in a changing world

Survival of the fittest is such a common adage that one rarely imagines how widespread cooperation is in the natural world. Mutualism is an interaction between two species where both organisms rely on each other for some advantage. The work of Borges has uncovered many elegant mutualistic relationships. These relationships are often inseparable — one organism cannot survive without another.

Figs and fig wasps are an example of a beautiful mutualism. Female fig wasps enter the fig to lay eggs inside the fig’s flowers, pollinating the flowers in the process. The larvae develop inside the safe space of the fig, feeding on the flower tissue.

Pollination is an extremely common mutualism, but will also be profoundly affected by climate change. As seasons change, trees fruit and flower haphazardly, trying their best to keep pace. Insects that depend on these flowers for nectar may not have hatched yet, or may have already died. In turn, the tree suffers the next year.

“I am most concerned about temperature.” Borges observed, frowning. “Insects are ectotherms [cold blooded]. Fig wasps do get less active as temperatures rise. Wasps have to come from long distances, and the question of how they survive these flights under high temperatures is concerning.”

However, it is not that animals cannot adapt. Umesh Srinivasan, Assistant Professor, the Centre for Ecological Sciences, highlighted that animals can physically move, shifting to cooler areas, change behaviours, or even change physiologically. “These have implications for species interactions. For example, if migration timings are changing, you have two species suddenly competing for things like nest resources.”

Heat waves are also a significant concern, as those lasting just two to three days can even decimate insect populations. “Going forward, we really need more information on temperature, wind speed, soil temperatures… everything at a much finer level,” Borges commented.

Besides microclimate data, baseline information is also missing right now. Although species interactions shape the world around us, there are so many fundamental gaps in information. It prevents predicting the world of the future.

Whether one looks at global patterns of climate, bridging disciplines through work or embodying the art of experimentation, Borges highlights the importance of natural history knowledge. “Being grounded in natural history is what informs data. Even large-scale datasets and huge networks need a background of natural history…. If you are interested in ecology, go outside. Better yet, go outside with someone who knows more than you.”

About the author

Yams Srikanth is an ecologist whose other interests include science communication, writing and trying to build a better world. When not languishing in front of their laptop, they can be found outside poking at any insect, bird or plant. Their undergraduate degree in Biology and Education, along with a Master’s in Wildlife Biology has given them skills and perspective to help readers appreciate and handle the environmental issues of the Anthropocene. They also write about queer and trans rights and their intersections with STEM and education.

Add a Comment