“For me, it’s all been about the love of science.”

“I have multiple types of days. No two days are alike,” she laughed, eyes sparkling. Mondays are for planning the week and the month, Tuesdays and Thursdays for meetings and developing new business ideas, Wednesdays for long term activities (strictly no meetings), Fridays for projects, Saturdays for relationship-building. Sundays are Jugnu Jain’s own, leisurely and carefree, filled with books, music, good food and yoga.

The first time you hear it, you are taken aback by the structured execution of her week. Then you realise with a jolt that she organises her work week the way she would draw up a laboratory calendar, cutting through overlaps and disruptions, with the precision of a scientist’s mind. For after all, she is a scientist by training and an entrepreneur by choice.

She empowers India

“Jugnu Jain has been changing the landscape of biobanking in India. Sapien Biosciences has emerged as India’s first central biobank predominantly upcycling medical waste for R&D of new diagnostics, drugs, and reagents. #SheEmpowersIndia.” When 50-something Jain received the “Women Transforming India” award from Government of India’s premier think-tank, NITIAayog, in 2020, it felt like homecoming.

The molecular geneticist, cell biologist, inventor with three patents to her name had come back home to India after 26 years.

The more she became a global citizen, the more her identity as an Indian evolved. “The Nehru Trust scholarship for a PhD at Cambridge was a career-defining award,” she said. “It allowed me to do genetics, a field not advanced in India at that time, but it made me more of an ‘Indian’. “I became more conscious that I was representing my country.” The appeal of biobanking also lay there. Currently, apart from the US and western countries, China has strong biobanks and genomics. “I thought, if China can, why can’t we?”

Receiving the NITI Aayog Women Transforming India award from Union minister Rajnath Singh

“I realised that India did not have a proper biobank,” she said, “but I did not know if I would be accepted here.” She teamed up with like-minded scientist-entrepreneur, Sreevatsa Natarajan, to set up Hyderabad-based Sapien Biosciences in 2012 — the country’s first pan-India and commercial biobank.

Jain belongs to the rare breed of scientists founding startups. Here, too, women are a minuscule minority worldwide. In biotech, however, the numbers are growing compared to other industries in India, with 33 per cent women entrepreneurs (about 1,000). Although the proportion of female co-founded companies has doubled in the last 10 years, only three per cent of investment goes to them globally. “We have received zero funding from the government even after eight years in business,” she pointed out.

“For me, it has all been about the love of science,” she said, recounting a journey full of exploration and discovery, obstacles and challenges, surprises and chance. It’s also been about a dream pursued ferociously and flying in the face of fear, opposition and conventional wisdom.

It’s the thrill of understanding life at the most elemental level of cells, genes and molecules that made Jain defy her father’s wish that she become a teacher, disregard the resistance at GB Pant University of Agriculture to have her as the only woman student in her batch in Plant Breeding and Genetics, and pursue PhD far away in a foreign country.

Long before the Human Genome Project took off in 1991, the joy of unlocking the secrets of genes saw her make a play for global science at institutes of excellence – University of Cambridge, UK, and Harvard Medical School, US — where you can catch Nobel-winning professors ride their bicycles to work and share a coffee with students.

As biology became the frontier science of the 21st century, the excitement of discovering genetic defects in the blueprint of one’s body and taking proactive measures to stem the consequences, made her join the top US biotech firm, Vertex Pharmaceuticals — a startup that became a billion dollar global biotech business, known for its transformative medicines for life-threatening diseases.

At the cutting edge

Jain specialises in non-infectious diseases, especially cancer and immunology. Globally, scientists are looking at a patient’s own genes and immune system as alternative treatment modalities. At the cutting-edge of research are human biobanks, a repository of patient samples — tissues, blood, urine or other body parts and fluids — from which they can gather data and insight into diseases.

With Biocon chief Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw

“Leftover tissues from surgery or diagnostic procedures, say, cancer tissue, blood or urine, are highly sought after worldwide by researchers, diagnostics, biotech and pharma companies,” she explained. They help validate drugs and targets, identify risk factors, help in early diagnosis and customise treatments. “Results from human tissue samples can help determine which drugs are worth developing,” she said.

India doesn’t have this kind of data bank for native tissues to help us understand what are the risk factors for diseases we suffer from, at what age and what treatments are effective. “Without this kind of large-scale population knowledge, government policies cannot be driven by science and evidence,” she explained. “Whenever you are writing a paper, say on cancer, you start citing global statistics. And the available stats from India are typically several years old.”

A path of her own

As she carves out a path, Jain reflects on the coronavirus pandemic of 2020. “Covid has not been too bad for us, we were somewhat prepared for it,” she said. In the last one year, she has reorganised the business model of her startup, cross-trained her staff, encouraged them to work from home (largely) and enabled them to build and mine the constantly growing deep, real-world data sets in cancer. “Unlike many others, we did not give anyone the pink slip, slash salaries or increments,” she pointed out. What she earned was worth much more – good will, loyalty and a streamlined workflow.

She did not forget to reserve some time-out for herself, too. Away from cell phones and virtual meetings, she would dig online to learn, network, reach out for business development and grow. She participated in accelerator programmes for women entrepreneurs, virtual world conferences for science and tech women, and she applied for challenges and competitions, to build the brand equity of her company. In August 2020, Jain walked away with the winning prize at the TiE Women Finals in Hyderabad for her pitch about the future of her company.

Jugnu Jain has cracked the problem: In science, as in enterprise, the road ahead lies in finding opportunities where others see dead ends.

At a contest in Delhi University, as a student of Miranda House

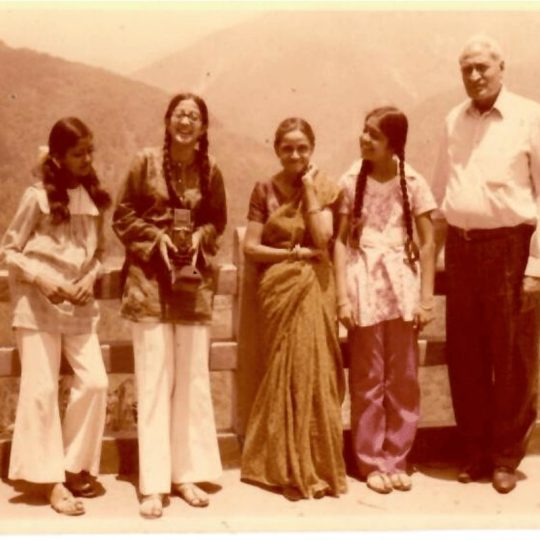

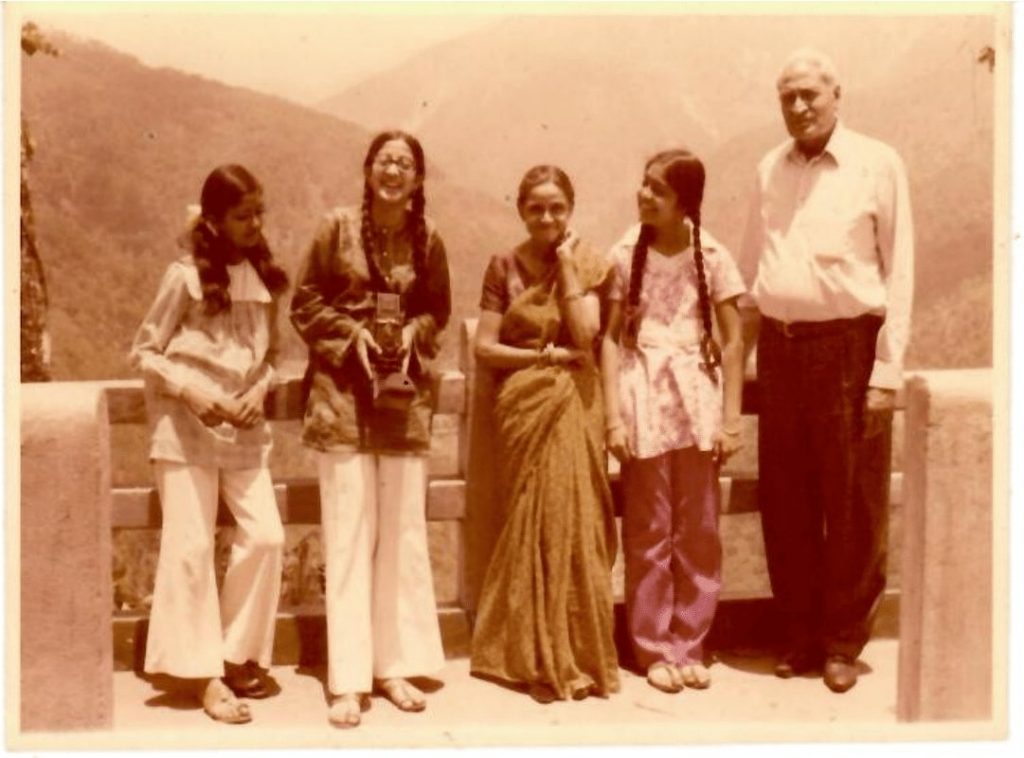

From the family album, with her parents and two sisters

An adventure junkie

Meeting then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi as a Nehru Cambridge scholar (Jain next to Sonia Gandhi)

Also By Damayanti datta

“If you are the only woman in the room, so what?”

By Damayanti Datta

Technologist, inventor, innovator, entrepreneur, Geetha Manjunath, harnesses the power of artificial intelligence to detect lurking disorders—from breast cancer to COVID-19.