Posted on August 15, 2023

She reposed trust in plants to tide over tough days in foreign lab

By Gowthami Subramaniam

Battling bias and returning home without a published research made Jaishree Subrahmaniam so resilient that she managed to beat 12,000 applicants to emerge as the recipient of prestigious Marie Curie Fellowship

“I chose an independent path for myself — a continuous mind marathon in the form of academic research, where one must constantly prove worth to secure a grant. I wanted my contributions to be a testament of my capabilities”

Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu: A plant biologist, Dr Jaishree Subrahmaniam (30) has been a fighter all her life. She resisted in her own unique style when forced into an engineering course, notwithstanding her interest in botany.

“I purposely failed an exam and my father was left with no option but to enrol me for BSc Botany in Miranda House in New Delhi. It was there that my passion for plants bloomed fully. The teachers were immensely passionate about science, and together we nurtured a genuine curiosity for the intricate world of plants. It laid a solid foundation for my future in scientific research,” says Jaishree.

As expected, Jaishree topped in the university exams and automatically gained admission to MSc Botany at the University of Delhi. She was confident about pursuing research abroad, though it took three years during the course of her studies to convince her father to allow it without getting married.

“I chose an independent path for myself — a continuous mind marathon in the form of academic research, where one must constantly prove worth to secure a grant. I wanted my contributions to be a testament of my capabilities,” she affirms.

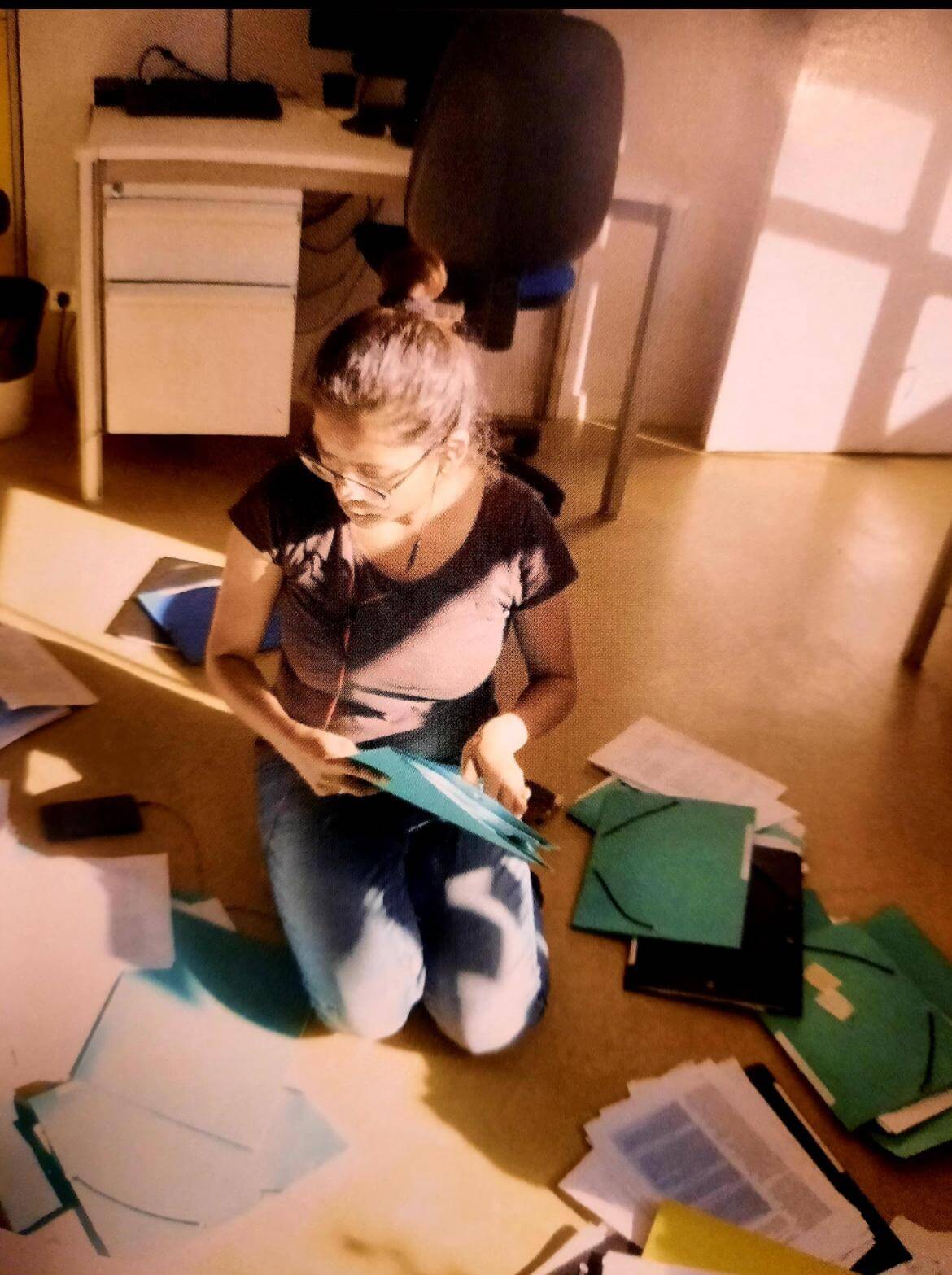

Jaishree in the midst of her PhD work

The quest begins

‘How do plants talk to each other and are they actually smart?’ This was the research question that Jaishree explored. She sought a fusion of ecology and sociology in her research. By chance, she met in Bengaluru Dr Megha Agarwala, who was doing postdoc at Columbia University. Her work on forest and community rights was inspiring, and Jaishree soon joined her as a research assistant.

“I spent the next one year working in the forests of Uttarakhand, aiding different projects on human-forest relationship,” says Jaishree, who also was at Columbia University during her assistantship. Within that short stint in 2016, Jaishree was selected as one of the top 20 students globally for the ‘Young Scientist of the Future’ programme at the TULIP Summer School in France.

"During the internship, I presented my project to scientists from various universities. I was thrilled when my project was chosen, receiving the required funding with a principal investigator (PI). I was among the four students who got selected for this fellowship in France."

Envisioning a vibrant academic world of cultural exchange, Jaishree joyfully started her PhD in Université Toulouse III – Paul Sabatier, during early 2017. However, the reality disappointed her. “As the first and only non-French woman in the lab, I faced constant bullying. Once my PI found it amusing to push me off a mountain. I was in tears, pleading with him not to. My colleagues photographed and called that funny,” she alleges.

“My university failed to support me even as my colleagues morphed a photo of a naked woman kissing an old man with my face. They circulated the image via emails and even pasted the photo outside my office,” she recalls. “However, I stood up to him against the authorities once I graduated, but yes, they are still there enjoying academic life with no repercussions”

Under mounting pressure, Jaishree spent two-and-a-half years researching plant behaviour. “I demonstrated the systemic flaws in a colleague’s experiment. Unfortunately, I did not receive credit due to the PI’s bias against an Indian woman disproving a French man.”

Jaishree completed her PhD, but the hardships did not end there. “During my graduation, my PI deliberately kept my parents outside in the rain, refusing their entry into the ceremony hall. It left me shattered without being able to do anything,” she alleges.

Women in ecology research spend extended periods in the forests and outdoors. Recalling a specific incident, she says, “When I hesitated to climb a cliff, my PI insinuated that all women were incapable of pursuing ecology unless I succeeded. Feeling guilt-trapped but also forced, I reluctantly took on the challenge.”

“Despite highly positive comments like ‘going beyond the scope of a typical thesis’ and ‘a new direction to biology’, my PI denied publication of my thesis and left me at his mercy. He did not pay for the last three months of my PhD either. My unemployment phase coincided with the COVID-19 period. I am unsure if my thesis would ever see the light of the day,” she rues.

A university staff member, on condition of anonymity, reveals, “I have personally witnessed cheerful Jaishree becoming very sad… I have tried my best to comfort her during those difficult times. The sexist jokes made by her team were so hurtful that even French women…. would be deeply offended. I really don’t know how she managed to handle all of that.”

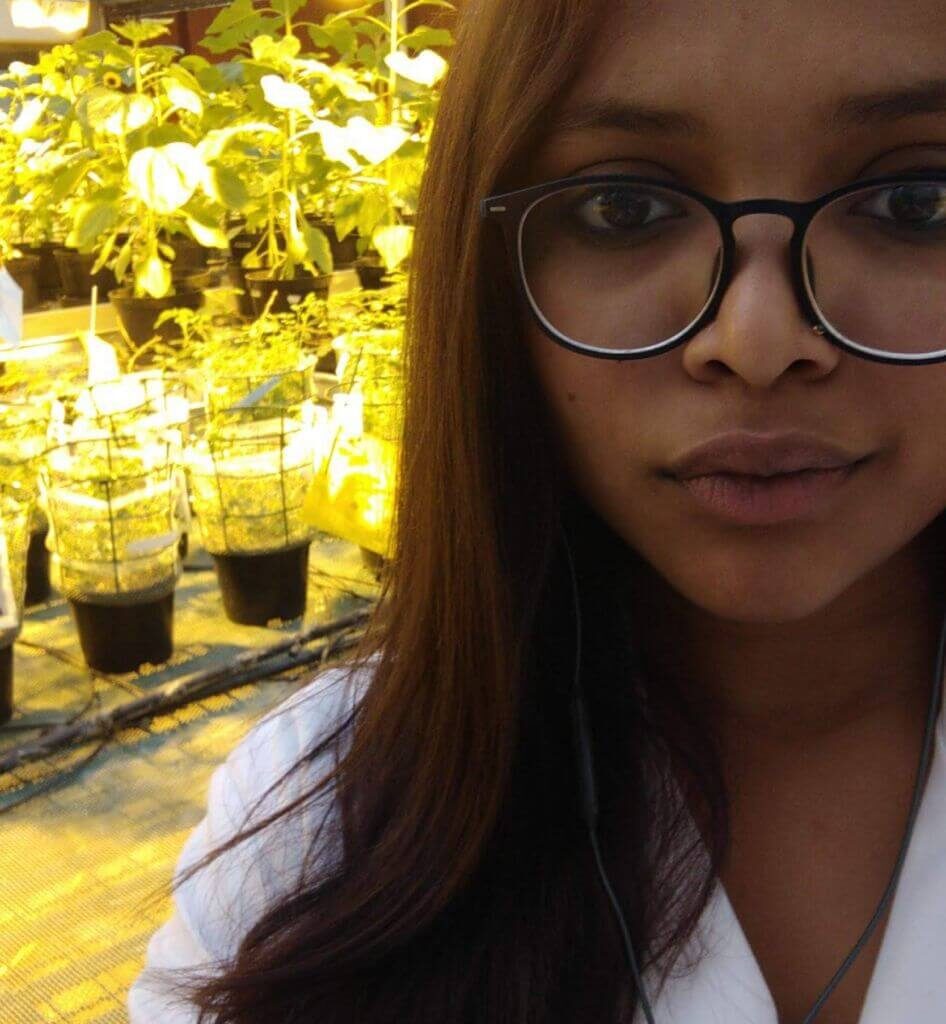

Jaishree conducting research in the lab

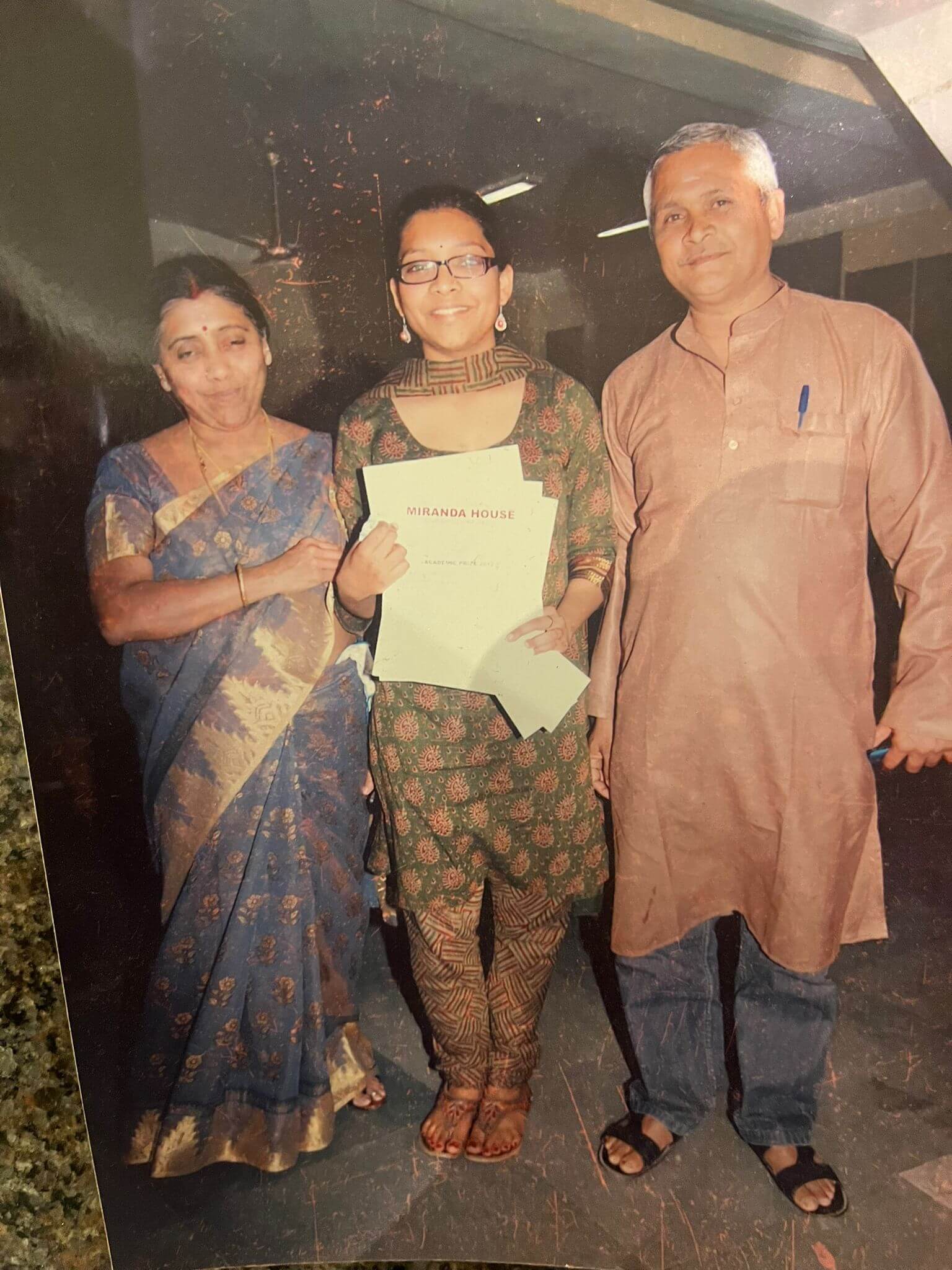

Jaishree receiving her PhD

“Despite battling depression, she would spend a lot of time in the green lab, engaging with plants and conducting research. Plants seemed to be her only source of comfort. If I were in her place, I do not think I would have pursued a PhD... There are many others, who have also had problems with the PI and have filed complaints. However, the PI is still employed by the university," the staff member says.

After completing her PhD, she returned to India in 2020, but without any published research. It was disheartening, but Jaishree continued to apply for grants. She claims bad recommendations from her PI failed her applications. So, when she applied for the prestigious Marie Curie Fellowship without any recommendation letter or published thesis, she had little hope.

Then came the twist in the tale. “From 12,000 applicants across the globe, I was chosen for the fellowship based solely on my proposal. Though I did not have all the traditional metrics like high impact publications or an extensive postdoc career, my proposal involved bringing together many aspects of science, including molecular biology, evolutionary ecology, population genomics and analytical chemistry. I was able to form collaborations with people who are experts in these fields for my work. It helped my application stand out,” shares Jaishree, who pursued her fellowship at Aarhus University in Denmark.

According to Jaishree’s friend Dr Rikke Reisner Hansen, a postdoc at the Department of Ecoscience, Aarhus University, her main motivation lies in the pursuit of breakthroughs in her lab. “The only time she breaks down is when things do not succeed in her lab,” Hansen recollects.

“As a Marie Curie Fellow, my current work integrates population ecology, evolution, chemistry and genomics to understand how plants communicate with each other below the soil surface. It has been a ‘black box’ in our understanding so far, but I developed a method recently to study the chemicals that plant roots secrete, using many disciplines of science (ecology, evolutionary biology, genomics, molecular biology and chemistry,” shares Jaishree.

“Think of them as a kind of ‘whisper’ between plants beneath the soil,” Jaishree says. By understanding these signals, she aims to uncover the secret language plants use to cooperate with one another. It’s not just about plant-to-plant communication though. The applications of this work have broader implications. “By tapping into this natural cooperation, we can potentially design more resilient and efficient agricultural systems, where plants work together to enhance nutrient uptake, ward off pests, and adapt to changing environmental conditions,” she enthused.

Providing key insights into Jaishree’s research, Hansen says it has wide-ranging applications in agriculture, medicine and biodiversity. “While funding and the basic nature of her research pose challenges, I envision Jaishree leading a thriving lab with numerous students and colleagues in the next 10 years.”

Foray into mental health

Despite her resilience, Jaishree learnt that academia’s structure made women and international communities, particularly when combined, vulnerable to bullying.

“At one point, I felt a complete loss of self-respect. I sought therapies to find closure, but I am still processing everything.

Jaishree in her lab among the various plants under test conditions

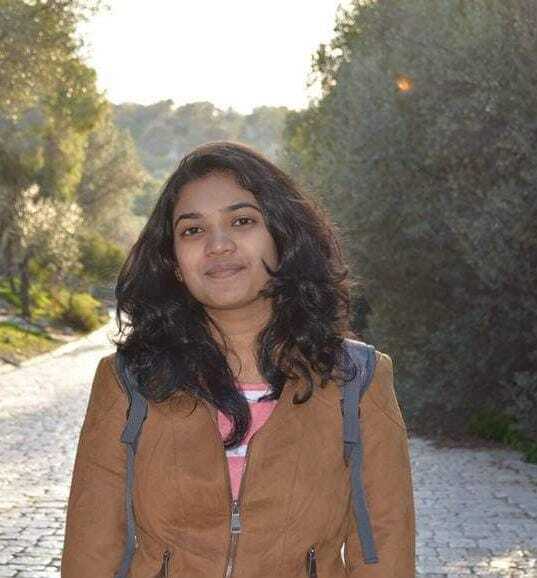

Jaishree with her friend Dr Rikke Reisner Hansen in the Department of

Ecoscience, Aarhus University

When she observed that many of her friends had the same issue, she wanted to establish a mental health support network for early career researchers in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM). “Although I received private support, public endorsements were hard to come by. The lab’s head did not consider it worth people’s time and resources,” Jaishree says.

Upon meeting Dr Roopali Chaudhary, Chief Executive Officer, Lotus STEM, an NGO supporting South Asian women in STEM, she readily embraced the concept of establishing a non-judgmental secure environment and launched a programme titled Paksh. “Despite Paksh being initially designed for international students, we decided to open it to all early career researchers in STEM.”

“Paksh provides a secure platform to come together and share their experiences and challenges in navigating academia. It is an exclusive programme that admits members through a selective application process. The four-month programme holds bi-weekly online meetings, where we encourage participants to discuss their journeys and struggles in academia openly,” says Jaishree.

“We recognise some may require additional support from mental health professionals. In such cases, we direct them to the appropriate resources.

Dr Zille Anam, a participant in the Paksh programme during her PhD, shares, “Academia being very competitive in nature, mental health is neglected and it can get really difficult without appropriate support systems.”

Jaishree serves as the Chair of the Science Policy Working Group in the Marie Curie Alumni Association, and a guest adviser for the Plant Ecology collection in Open Research Europe. She had also acted as an External Policy Adviser and Board Member of the Initiative for Science in Europe.

I never want her to leave academia for family. Botany completes her, and I believe it strengthens our relationship. As someone equally passionate about science, I enjoy listening to her research. Our conversations are always interesting and thought provoking. If she were a housewife, what would we talk about?" wondered Jaishree’s husband Kartikeyan Rajadurai, adding “her first definition is of herself, not as someone's daughter or wife.”

Her husband, Kartikeyan Rajadurai: “Botany completes her, and I believe it strengthens our relationship. As someone passionate about science, I enjoy listening to her research”

With her parents on the day she received her BSc degree in Botany from Miranda House in New Delhi

Jaishree is on a mission to decode the subterranean conversations between plants, and revolutionise the way we approach sustainable agriculture

When she observed that many of her friends faced similar issues, Jaishree thought to establish a mental health support network for early career researchers in STEM

About the author

Gowthami Subramaniam is an independent journalist and documentary filmmaker. Her work highlights stories around women, energy, environment and climate change. Her work can be found on 101Reporters, CarbonCopy, Mongabay, The News Minute and more. She is an Earth Journalism Network grantee, and a Thomson Reuters Foundation and Global Centre on Adaptation fellow for Locally Led Adaptation. She was recognised as ‘Journalist of the Month’ in March 2022 by International Journalists’ Network and also as one of the ‘Emerging Producers of 2021’ by the World Congress of Science and Factual Producers.

Add a Comment