The chemist fighting India’s invisible pollutants

How Prerna Sonthalia Goradia is building molecular filtration systems that target the toxic air and water contaminants that are not always visible

By Saishya Duggal

| Posted on January 13, 2025

Prerna Sonthalia Goradia talks about Mumbai with the easy familiarity of someone who has breathed its air, both the smog-choked and the wild. Growing up amid cramped lanes, chronic water shortages, and the steady haze of pollution, she learned early what environmental neglect feels like. Even on our video call, the painted skyline behind her, smokestacks, high-rises, echoes the city she knows too well. Yet she also remembers Borivali National Park, that improbable 100-square-kilometre lung in the middle of Mumbai, where she first understood what nature should look like. The collision between those two worlds has shaped her ever since.

Today, she’s the founder and CEO of Exposome, a materials chemistry provider that innovates in the molecular filter segment to transform industrial emissions and effluent treatments. But the path to this point was no smooth sailing. “Women in our family typically didn’t have careers,” she recalls, though that was never going to stop her. At just 21, she left home (after some hard-won persuasion) to pursue a PhD in materials chemistry at Michigan State University, building on a BSc, MSc, and a simultaneous diploma in environmental engineering in Mumbai. With a half-knowing smile, she dubs her younger self “overambitious.” It’s easy to see why. Even back then, she was certain that engineering and chemistry needed to intersect to drive real environmental innovation. “People don’t deliberately set out to pollute,” she offers. “But gaps in technology leave them without alternatives.”

Prerna being recognised for Exposome’s efforts at CII’s Startup Summit

For over four years during her Ph.D., Prerna was immersed in water chemistry, focusing on a particularly stubborn class of pollutants: metallic impurities. Though not always visible, these traces of metal in water affect everything—from drinking supplies to industrial discharge. Her research led to the development of a cost-effective, portable device capable of detecting these impurities with precision; this technique, along with a specialised material that responds to metallic contaminants when an electrical bias is applied, accounted for the breakthrough.

Despite some of her work being used on the International Space Station to detect silver in onboard water systems, Prerna insists she was nowhere near prepared for the rigours of a Ph.D. “I really wasn’t!” she admits sheepishly, instead crediting much of her success to her advisor, whom she calls “quite literally one of the best in the world at this” (advanced materials). “He wanted most of his students to go from the first principle,” she remembers appreciatively, noting that his emphasis on practical solutions over pure theory likely shaped her approach to materials chemistry for the rest of her career.

After graduating, she joined the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as an NRC postdoctoral fellow. She then joined a startup, NanoSelect, Inc., as their first chemist hire. Both roles, as she puts it, “tied up nicely” with her Ph.D. work in water chemistry. She later moved to ATMI, a supplier of materials, equipment, and services in semiconductor device manufacturing—here, she worked on absorbents, materials that can selectively remove pollutants.

Prerna presenting at the Women in Tech Leaders Luncheon hosted by the Consulate General of the Netherlands

Glass Ceilings, Patent Walls

Her next role brought her back to India to join Applied Materials, a global provider of materials engineering solutions. Naturally, I asked how her experience as a woman in STEM differed between the US and India. She paused before answering. “Engineering has always been male-dominated. You see more women in chemistry and biology, but leadership roles still tend to be held by men.”

At university, she hadn’t faced overt barriers, but the higher up one looked, the fewer women there were—a glass ceiling that was hard to ignore. In Michigan, she had simply noticed the imbalance; at Applied Materials, as part of the management, she could no longer look past it. As a Deputy Director, the scale hit her fully: “Sometimes,” she muses, “it felt like 95% of the people around me were men.”

What, then, bridges this gap? Within these realities, some spaces were trying to tip the scales. Applied Materials supported the development of an inclusive workforce through its Women’s Professional Development Network (WPDN), of which she became a part. Similarly, during her time in the U.S., organisations like the American Chemical Society’s Women Chemists Committee (WCC) underscored an ongoing recognition that women needed more encouragement in the field.

Another tangible way for women in STEM to claim space, especially where recognition is slow to arrive, is through patents. Prerna’s first patent came from her time at Michigan, and since then, she has amassed more than 30 across various roles. She attributes her prolific patenting record to the environment at Applied Materials, which “had a deep-rooted culture of innovation. The company understood patenting as a way to protect its work. My manager, Robert Visser, especially encouraged our team to tackle a wide range of problem statements, semiconductor processes, evolving node sizes, emerging materials.” With the industry moving at breakneck speed (and being housed in the CTO’s office), much of her team’s work was seminal.

But if patents were a way to secure her contributions, Prerna was about to make a move that threw security out the window. After nearly 13 years in the industry, she decided to pivot to something most people told her was “crazy”: entrepreneurship. “People told me it was a mad decision,” she says wryly. “I was walking away from a stable job, great pay, and a team I had personally hired and trained—for uncharted territory.”

And as if the leap itself wasn’t bold enough, she launched her venture, Exposome, right in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic.

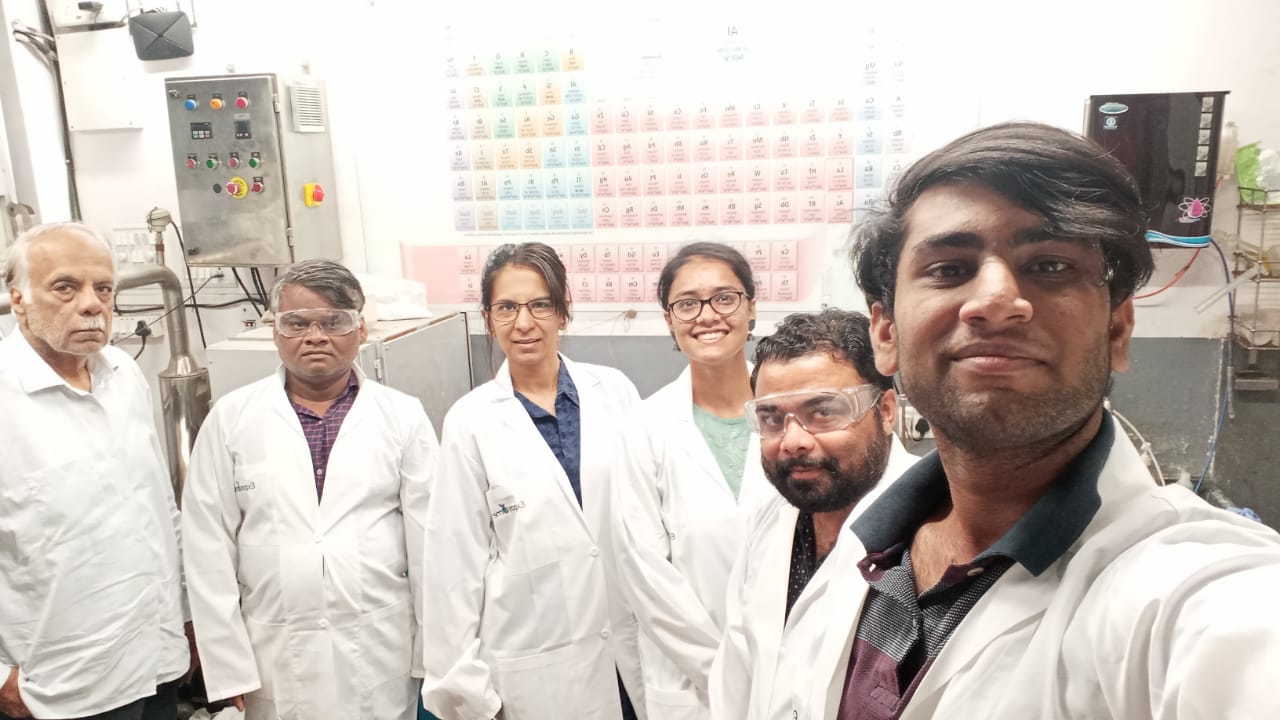

The Exposome team in the lab, where they undertake extensive R&D to develop molecular filtration solutions

Filters and faith

Exposome was born out of a critical gap in tertiary treatment solutions for air and water. At the time, cost-effective molecular filtration for water was virtually nonexistent, and regenerable air filters had yet to be developed. In its first year, during the pandemic, the team focused on antimicrobial filters before gradually pivoting to molecular filtration technologies for both air and water.

Prerna describes this phase as one of the most challenging yet. “In our industry, refining technology and scaling production is grueling because validation is slow, customer trust takes time, and infrastructure demands are high.” She sounds weary, and rightfully so. Research shows that early-stage climate tech typically demands five to six times more capital than high-growth sectors such as fintech or quantum computing, making funding a steep uphill climb. Scaling is inherently slower for Exposome, as with most climate-tech companies, because building physical assets takes time—on average, nearly seven years for such businesses to reach Series D.

At Exposome’s showcase of its offerings for optimising industrial pollution treatments

And yet, what surprised me most is this: if climate-tech entrepreneurship is such a tedious marathon, it’s women who seem to be lacing up for the long haul. Nearly 40% of cleantech startups in India are now led by women. “Women are used to doing hard things quietly, I guess,” she says when I ask why. “We don’t expect quick rewards; we keep our heads down and follow through. And maybe that’s exactly what this sector needs.” She pauses, then adds, “And maybe we care more because we feel the stakes differently.” It lands. For Prerna, the future isn’t abstract; it’s what’s on the dinner table, it’s the air her children breathe.

Now, with their own manufacturing facility and backing from investors like the Colossa WomenFirst Fund, Exposome has developed a portfolio of 30 specialised filters and addresses air and water contamination across industries such as oil and gas, electroplating, food and beverages, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and semiconductors. “We live and breathe innovation,” she says. “It’s deeply gratifying when you’re solving high-priority problem statements like removing corrosive gases and eliminating carcinogenic pollutants from water.”

And the impact is real: removing lead, volatile organic compounds, and microbial contamination addresses major public health challenges in India. As a pilot project, Exposome installed a filtration system at the 2025 Prayag Maha Kumbh Mela, the world’s biggest crowd gathering yet. Over two months, the system purified nearly one lakh litres of water daily, demonstrating both its large-scale potential and the urgent need for sustainable public water solutions.

“I suppose you could call me a late bloomer,” she chuckles, the self-deprecation obvious. “Most entrepreneurs kick off in their twenties, but I took my time.” Yet that hardly tells the whole story. Long before climate tech became a buzzword, Prerna understood the power of bringing engineering and the environment together. She knew where she wanted to be, knew, too, that technology could address some of the industry’s biggest challenges. She learned the fundamentals before setting out on her own, and chose to raise her children before fully committing to Exposome.

She is, for what it’s worth, an early, early bird.

About the author

Saishya Duggal is a public policy and impact consulting professional working at the intersection of tech, finance, and climate policy. She has undertaken projects with the UP Govt., the World Bank group, and Indian NBFCs. A graduate of Delhi University, her work emphasises the value of STEM in policy and its implementation. Her previous professional stints include those with Invest India and Ericsson.

Add a Comment