From urban slums to rural schools, this geneticist and teacher got kids curious about science

Sparking scientific temper using affordable tools and helping students learn by observing their surroundings make Sonali Kadam’s teaching style interesting and unique

By Aditi Subramaniam

| Posted on December 5, 2024

Sonali Kadam’s tryst with teaching began in late 2014 when a few class 10 students preparing for board exams asked her if she could teach them how the heart functioned. She had come to her native Dharavi, one of the largest bastis (slums) in the world, on vacation from Kolhapur, where she was studying biotechnology engineering at KITCoEK.

“They found my way of teaching biology helpful and from the next day onwards, I started taking one-on-one sessions,” Kadam recalled. The practice continued during the vacations next year as well when she taught short topics in one or two subjects by taking lectures.

During this period, she also started collaborating with Dharavi Diary, an NGO that provided free educational facilities for children living in the basti. All her students were attending government schools that did not have the right infrastructure or pedagogy. Kadam carefully curated a study plan to cover all essential topics to ensure that students who had fallen behind could bridge the gap.

Among her many experiments in teaching science was the use of foldscope in late 2015 as an experiential learning tool to teach biology and other disciplines such as physics, chemistry and maths. Foldscope is a paper microscope that combines low-cost materials with precision optics to visualize tiny microorganisms or larger samples such as insects, plants, fabrics, and tissues.

Meanwhile, her time in Kolhapur proved to be transformative. Born and raised in Dharavi, she had scant access to open green spaces and until she spent time in the forests, she couldn’t imagine the scale and variations of life that was living and breathing all around us.

She thought that if she couldn’t take the children from Dharavi to the forest, to experience what she did, then she will bring the forest to them. She collected a water sample from a stagnant puddle and showed them a whole other world that was thriving under their feet. “I wanted them to see that there is more to life than their struggle for survival,” she said.

Kusum Verma, one of Kadam’s earliest students who is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in nursing, fondly recalled how Kadam taught her concepts from scratch. “My family migrated from Uttar Pradesh, and I had joined a government school in Mumbai. At the time, my basics in biology were not clear. She patiently taught me concepts from scratch, and this helped me understand the subject. Her interactive sessions forced me to think about the things around me that I often took for granted.”

Kadam remembers how the experiments in chemistry and biology were always fun for the students

Kadam’s learnings and reflections from teaching biology to children like Kusum were particularly insightful since she had to simplify the concepts in a way that they could understand. She felt there was a need to increase their scientific temperament and spark their curiosity with the right kind of tools.

“In math and physics, I did not explore that much. However, we did many experiments in chemistry and biology. It was fun for students,” Kadam recalled. She remembered how students were fascinated to see a drop of water through a foldscope, with thousands of microorganisms present in it. “Almost every day, they would come to me with their questions and findings and we would have discussions around it.”

Kusum remembered the first time she used the foldscope. “Our teacher [Kadam] dissected a mosquito, and I could see even its minute parts. From this, I learnt how our skin, for instance, is made up of small skin cells.”

After completing her bachelor’s degree, Kadam worked full-time at Dharavi Diary for one-and-a-half years during the 2017-18 period. “I took more responsibilities at the NGO. Around the same time, I realised that I should pursue a genetic engineering course,” Kadam said.

The inspiration came from her rapidly evolving world view in which she could clearly see where she was on the caste-class ladder and how she was perceived both inside and outside her basti. The increasingly glaring everyday microaggressions had led her to question what was so different about her and fellow Dharavi residents, which behaviours were linked to deprivation and survival, and how much of this was hard-coded in the genes.

16 states, one mission

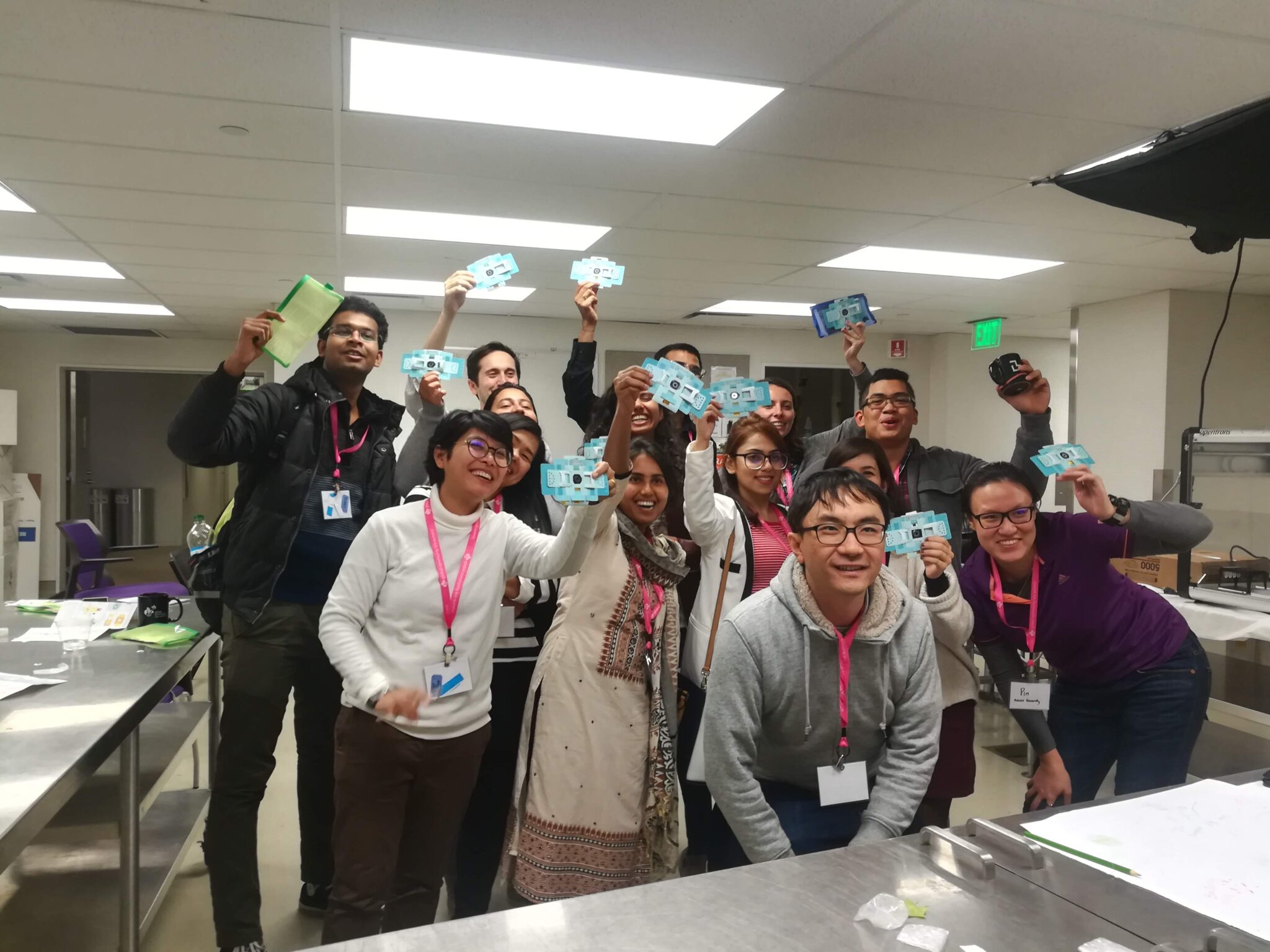

“All these experiences and experiments led me to a Foldscope Fellowship in 2018,” Kadam added. The fellowships are given to individuals who are passionate about teaching and training the next generation. She credits, Dr Shailaja Gupta from Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India (which was funding the fellowship) and Foldscope Instruments founder Dr Manu Prakash for the enriching opportunity.

During the two-year fellowship period, she travelled to 16 states to make science accessible to all. Her main goal was to do outreach in the most rural and tribal parts of India “to introduce science through foldscope by letting them experience the science themselves,” Kadam detailed.

In making science accessible and easy to understand at the grassroots level, Kadam ensured that her lesson plans were flexible and related to the topography of the place where she taught. Her classes were open to all, which meant students as young as 12 or as old as 60.

Her classes were not restricted to the confines of the classrooms and extended to the surrounding environment. Given that most sessions were held without the luxury of a laboratory, she taught her students to examine their surroundings. They would study the soil, trees and stones, including the beauty of microflora and fauna which are invisible to the eyes.

Kadam’s efforts introduced students to biodiversity, something that they were not consciously aware of before. “Our role was to introduce them to their surroundings through the lens of science… These areas are very rich in biodiversity. We took them for bio walks where we would introduce them to their surroundings — what kind of tree is this, why this tree is in a certain way, why it produces flowers and how to identify different trees just by observing their leaves or pollen. We would collect pollen and observe them through the foldscope. We would examine the structure of a flower, its petals and patterns in leaves. Similarly, we would observe different kinds of insects and ants.”

Aware and articulate, she was invited to deliver a talk on Slum and Science at the Global Community Bio-Summit 2018, organised by Dr David Kong, MIT Media Lab, Boston. She was also a part of the panel in a discussion on Nurturing Global Collaborations at the 2019 summit.

It was during a workshop at the National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bengaluru that Kadam met her future principal investigator. “I got to know about the real research happening in life sciences and was inspired to pursue it.” At the end of 2019, Kadam joined NCBS as a Research Assistant.

Batting for inclusivity

Eventually, she found her way back to what came naturally to her – teaching. Until recently, Kadam was a research associate at the Centre of Excellence in Teacher Education, TISS. “When I joined TISS, I was initially working on an Interactive Interactive Flat Panel project, which was part of a government initiative to install big screens in all government schools. Our task was to develop open educational resources or digital, open educational resources for this interactive panel. I have created a lot of interactive material on biology, and developed creative lesson plans to make the classroom more engaging.”

Later she started working on inclusive education. This was an action research project where the focus is on learning difficulties and other fiscal disabilities, while also considering social, economic and marginal backgrounds. “We assess the challenges that students face and check how we can improve their experiences of learning in mainstream schools. You must be aware that students with different abilities are put into special schools. We feel that all students deserve to be taught in one classroom, and the classroom should be inclusive,” she explained.

Kadam taught inclusive science pedagogy to second-year integrated B.Ed- M.Ed students and helped them make lesson plans more inclusive by observing their classes. She gave feedback on classes to make them more inclusive and wrote case studies of her experiences. “I am trying to understand how education can be more accessible and inclusive by helping aspiring teachers to make their teaching techniques more inclusive for a diverse group of students,” she said.

As part of the Foldoscope Fellowship, Kadam visited many rural schools like this one in Khalapur near Raigad, Maharashtra

Over ten years ago, Kadam started conducting regular classes on biology in Dharavi which continued through her graduate days

Back to the basics

She believed that her drive to do this came from her experiences in Dharavi. “A student from Dharavi doing well in exams is extensively reported on. While such an instance is definitely a matter of celebration, the narrative often implies that one can do anything if one puts one’s mind to it, which is in stark contrast to reality, wherein overcoming classist and casteist institutions is virtually impossible. Hence, there is a need today for a partial shift of focus to developing the educational infrastructure while addressing systemic means of discrimination that take form in several ways,” she cited.

As a teacher, she has noticed that education is not a priority for girls from socially and economically marginalised classes. They had to take care of the entire household as both parents would be working. These responsibilities increase with age. They always faced pressure to get married as well. However, for boys, it is different. They take up other jobs while at school itself to earn a living.

“The biggest challenge before us was to convince parents that their girls are doing good and they should continue their studies. That apart, parents are not aware of the career options in biology, other than MBBS, nursing and pharmacy. They think their children are not that prepared for competitive exams.”

Kadam felt that constant mentorship, coupled with continued support from parents, was necessary for such children to crack competitive exams. In addition, they still need to get their basics right. “Our NGO used to send students to private coaching classes by getting CSR funds, but they still need to work on the basics,” Kadam noted.

About the author

Aditi Subramaniam is a freelance writer based in Bangalore. She is currently pursuing her Master’s degree in Sociology at the Delhi School of Economics and has a background in Journalism. She is interested in questions of ecology, gender and development.

Add a Comment