Posted on 03rd October 2022

The small town girl behind the scenes of Pfizer’s vaccine rollout

By Saloni Mehta

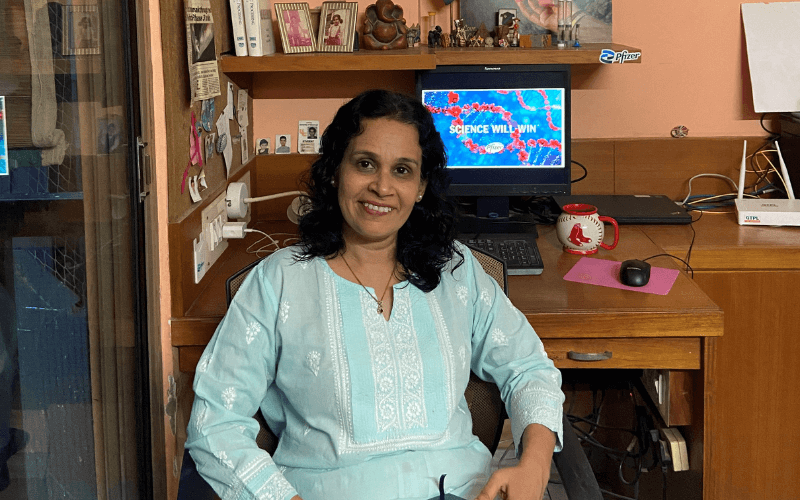

The Director of External Supply at biotech giant Pfizer, Poonam Mulherkar’s focus is unshakeable and her training in the production of high-standard pharmaceutical processes permeates her articulations and her actions alike.

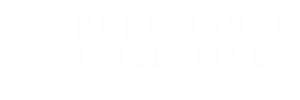

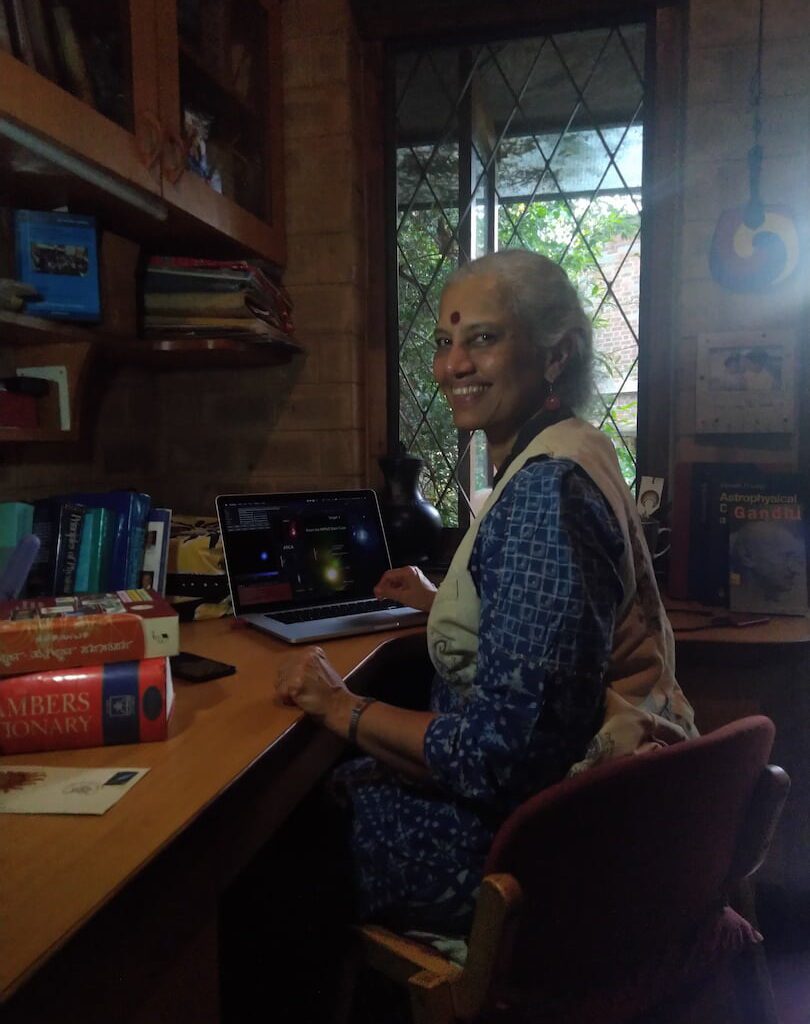

At her home office in Gandhinagar

Growing up in Bhopal, Poonam Mulherkar was always fascinated by the applied aspects of science in daily life. “All throughout my bachelor’s and master’s, I really wanted to get out and go into the industry,” she says.

So right after her master’s degree from the University of Cincinnati, she joined Genentech, a ground-breaking biotechnology research company, now part of the Roche group in the US. She worked in the lab as a process development scientist for about five years, followed by another seven years in facility design—an experience that she calls her “practical education”. The hands-on training she underwent at Genentech in those early years not only satisfied her innate desire to apply her knowledge to processes but helped shape her for bigger things to come.

Early days in Bhopal

Watching her father, who was a technical entrepreneur, tinker with cutting-edge technology inspired Mulherkar to follow in his footsteps. She was also deeply impacted by her mother’s work ethic.

My mother learnt finance and accounting from scratch, subjects that she had no training in, to help with my father’s business and in a few years, she had a strong grip on company finances. My mother taught me that if you have a ‘why’ you can figure out the ‘how’ if you are ready to put in the hard work”.

Her supportive parents encouraged her to dream big and follow her dreams and provided her with the opportunity to realise her true potential. When she was preparing for her engineering entrance exams, she was forced to either choose between appearing for the Madhya Pradesh state exams or the national-level Joint Entrance Exams (JEE). Although her mother realised that the JEE was far more competitive, all she had asked her was, “Which do you enjoy more?” This was especially unusual for girls to hear in a small town like Bhopal.

Recounting her experience at an all-girls school where she had no one to look up to, with even her school principal being sceptical about her wanting to clear the JEE, Mulherkar never let anything deter her in any way. Instead, she viewed her small-town background as an advantage.

Growing up in a small town meant I sometimes did not know what was happening in the outside world. This made it easier for me to just focus on the task at hand.”

Her absolute focus led her to IIT-Delhi for an integrated MTech degree in biochemical engineering, where she found comfort in a tight-knit group of friends. Being one of only 14 women in her batch of about 350 students was never a hindrance.

Adapting to change

Mulherkar has, indeed, adapted to shifts in her life with incredible patience and perseverance. The switch from working in the lab as an individual contributor to a managerial position was no mean feat.

Growing up in Bhopal, with her parents and siblings

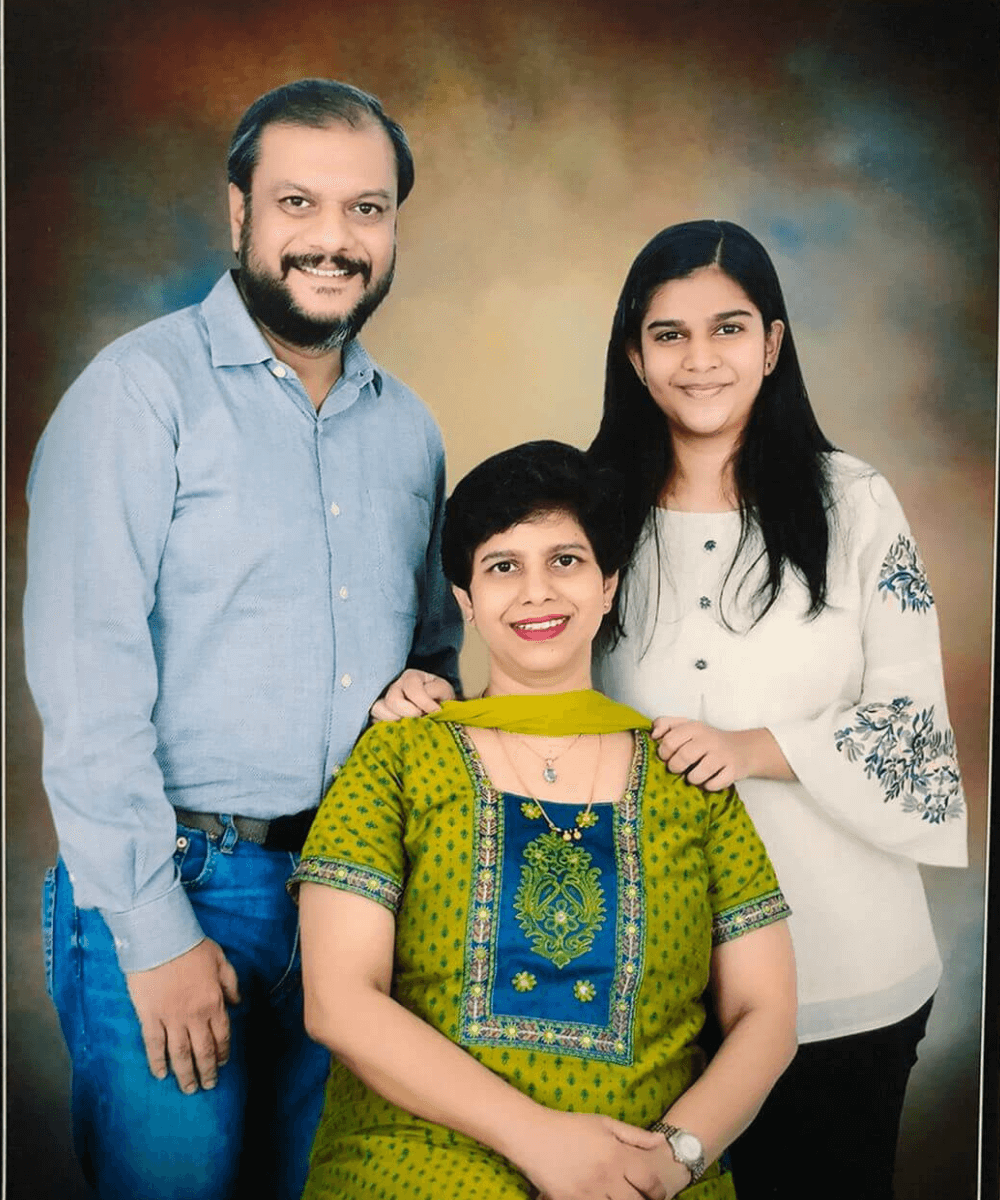

With her husband and sons

“It did not come naturally to me. As an individual contributor, everything is under one’s control. But as a manager working with commercial scale systems, your scope of influence is much bigger,” she says.

However, her seniors persuaded her to take the leap.

Sometimes, we just need a small nudge from someone who believes in us,” she reflects.

When she relocated with her husband and two sons to India in 2009, she decided to take a break from work and bounce back from burnout. During those 18 months, she wrote a book, Back to Pavilion: The First Years Back in India: Observations, Anecdotes & Insights of a Confused Desi, while working as an independent biotech consultant. It was during one of the consulting assignments that she looked at a technical design and realised how much she missed being an engineer. This led to her accepting the position of technical manager at Pfizer.

However, the shift from an American workplace to an Indian one was fraught with cultural challenges.

“As Indians, we do not want to show our messy side to our superiors. It is only our fair notebooks that must be on display, never our rough ones. But sometimes, science — especially applied science — is messy, and in the mess lies the truth. You have to be ready to accept and understand that not all experimental points will fall neatly on a straight line, if you want to make a difference in the real world of science,” she remarks.

Nature of work & Covid impact

Mulherkar is presently Director of External Supply at the biotech giant, where she leads teams involved in technology transfer. It’s the process wherein technological know-how from a manufacturing site is transferred to another to manufacture a product. Usually, most view technology transfer as a hardware-related process, wherein one needs to keep in mind the capabilities and constraints of the factories and their equipment. However, Mulherkar knows not to ignore “the other half of the puzzle: people”.

The capabilities, bandwidth, experience and constraints of the different people involved have to be kept in mind too,” she points out.

With her experience and expertise in biochemical engineering and pharmaceutical manufacturing, she has been instrumental in guiding her team in implementing intricate scientific processes. Mulherkar regularly works with CMOs (Contract Manufacturing Organisations) to help scale Pfizer’s product rollouts while ensuring quality.

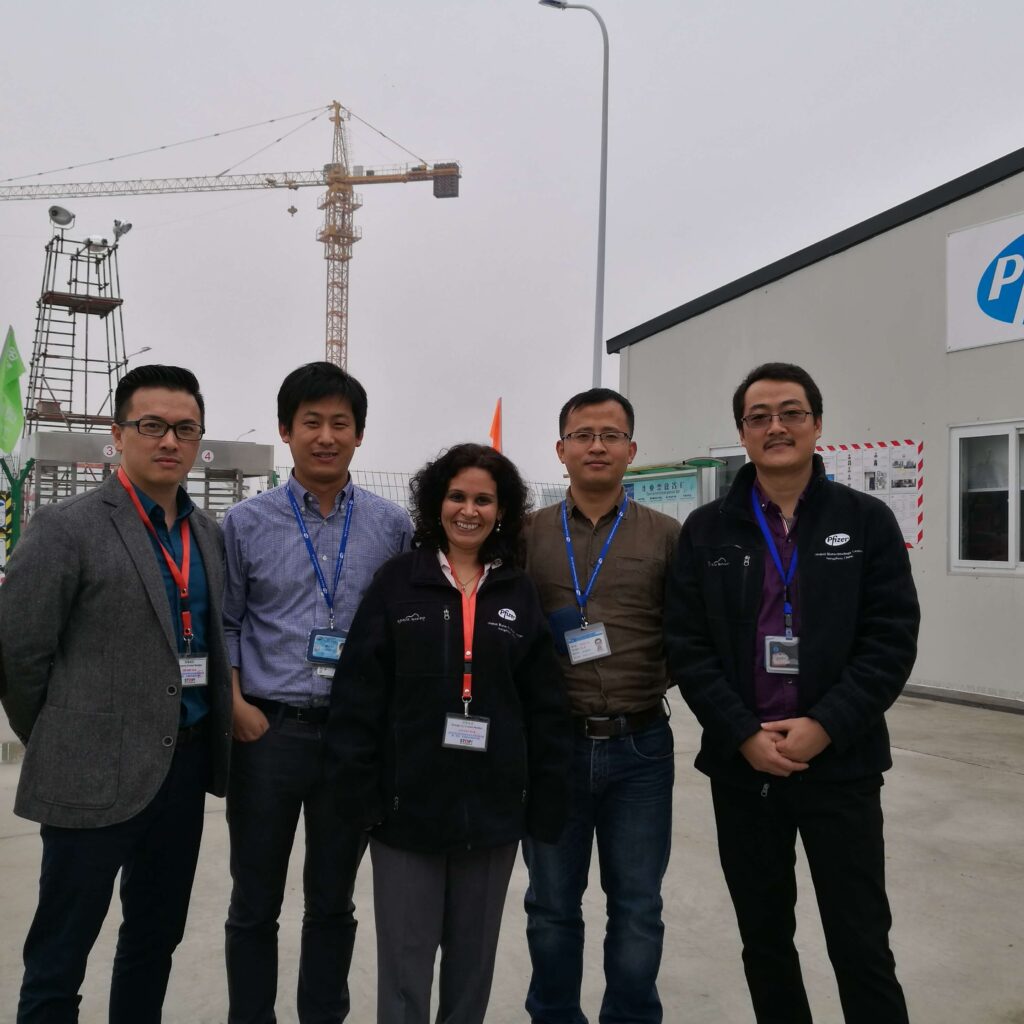

At a China facility under construction in 2016

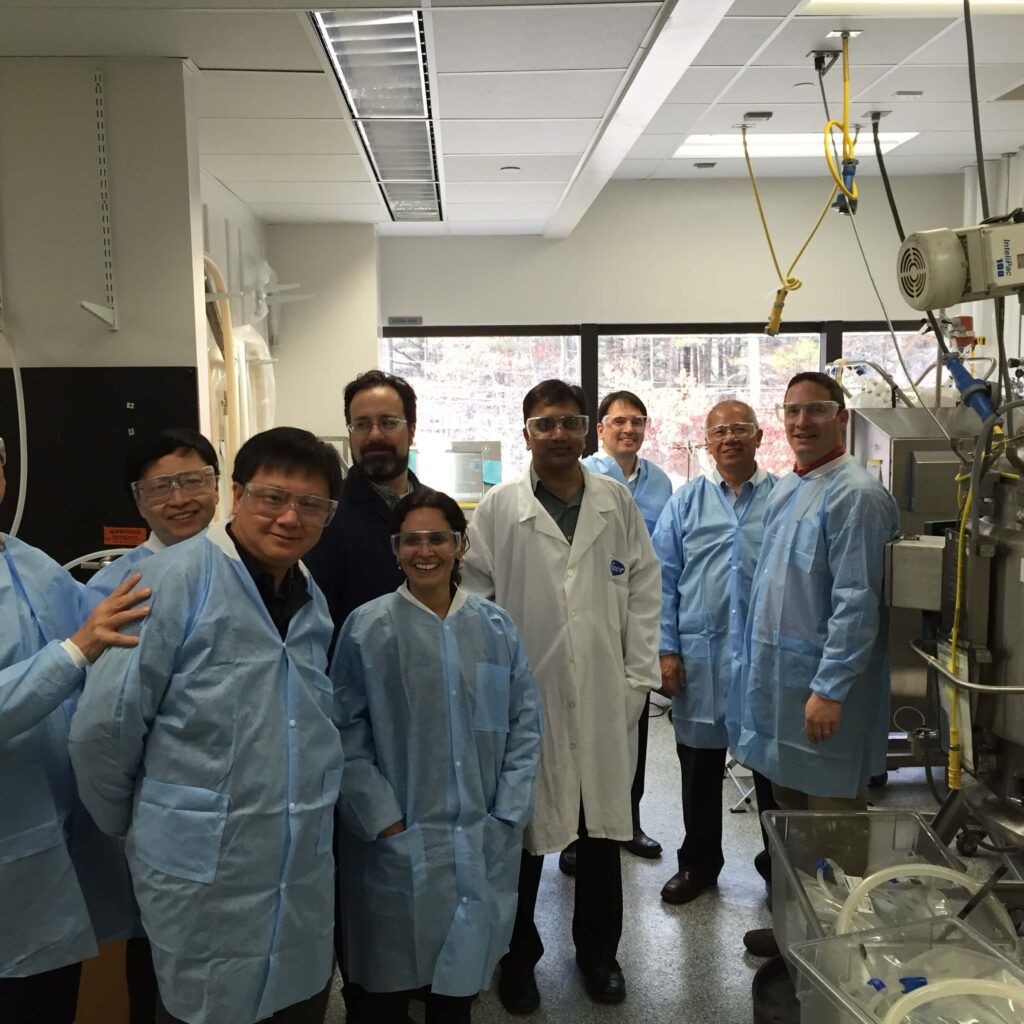

Celebrating Chinese New Year 2019 at work

In recent times, her work has included the rollout of the Pfizer-BioNTech Covid vaccine. She and her team were responsible for enabling the chosen external facilities for the production of the vaccine and ensuring rigour of the processes involved. This also involved training CMO teams on the various complexities of the manufacturing process. Transferring the know-how for every single step can easily take up to 2-3 years, but Mulherkar and her team ensured everything was completed within 9 to 18 months.

Even as she operates from her home office in Gandhinagar, she actively collaborates with teammates across the globe, including colleagues in Russia, Belgium, the UK, Italy and China. Interacting with a plethora of diverse people has also made her more empathetic.

“There are so many similarities at the core of who we are,” she says, explaining how she connects with her international colleagues. “I really feel like a global citizen. “

Whether it is imbibing people’s work ethic by observing them or figuring things out with her mentees, she is always ready to listen, understand, and collaborate. She also narrates how not being able to totally overcome her fear of deep water, even after multiple attempts, has made her more humble. “It has made me more empathetic towards people’s struggles. I realise that sometimes, like in the case of mental health disorders, circumstances are just beyond the individual’s control,” she elaborates.

As she enters the last 10-15 years of an active career, Poonam is looking forward to turning 50, travelling more often, and figuring out how to use her experience and expertise on a bigger landscape. She is excited about the technological evolutions in the pharmaceutical industry and wants to keep learning. And on the personal front, she hopes to finally learn how to swim in the deep without fear!

Future of women in science

Having witnessed several incredible women take charge during the Pfizer-BioNTech Covid vaccine rollout from across the world, Mulherkar is beyond optimistic about the future of women in science — now more than ever.

“Even my current group at work is mostly women and from different countries!”

And her first and foremost advice for all young women who want to pursue science is: “If you are someone who has the opportunity to study or work and have a support system, just go after your dreams. What limits you is only your fears and insecurities, nothing else.”

Find people who will support you; introspect and check if your conditioning is limiting you, and remember, hard work never fails and there's always room to grow," she concludes.

Edited by Rina Mukerji