Posted on 24th October 2022

An inclusive DIY guide to diagnosing developmental delays in children

By Priyamvada Kowshik

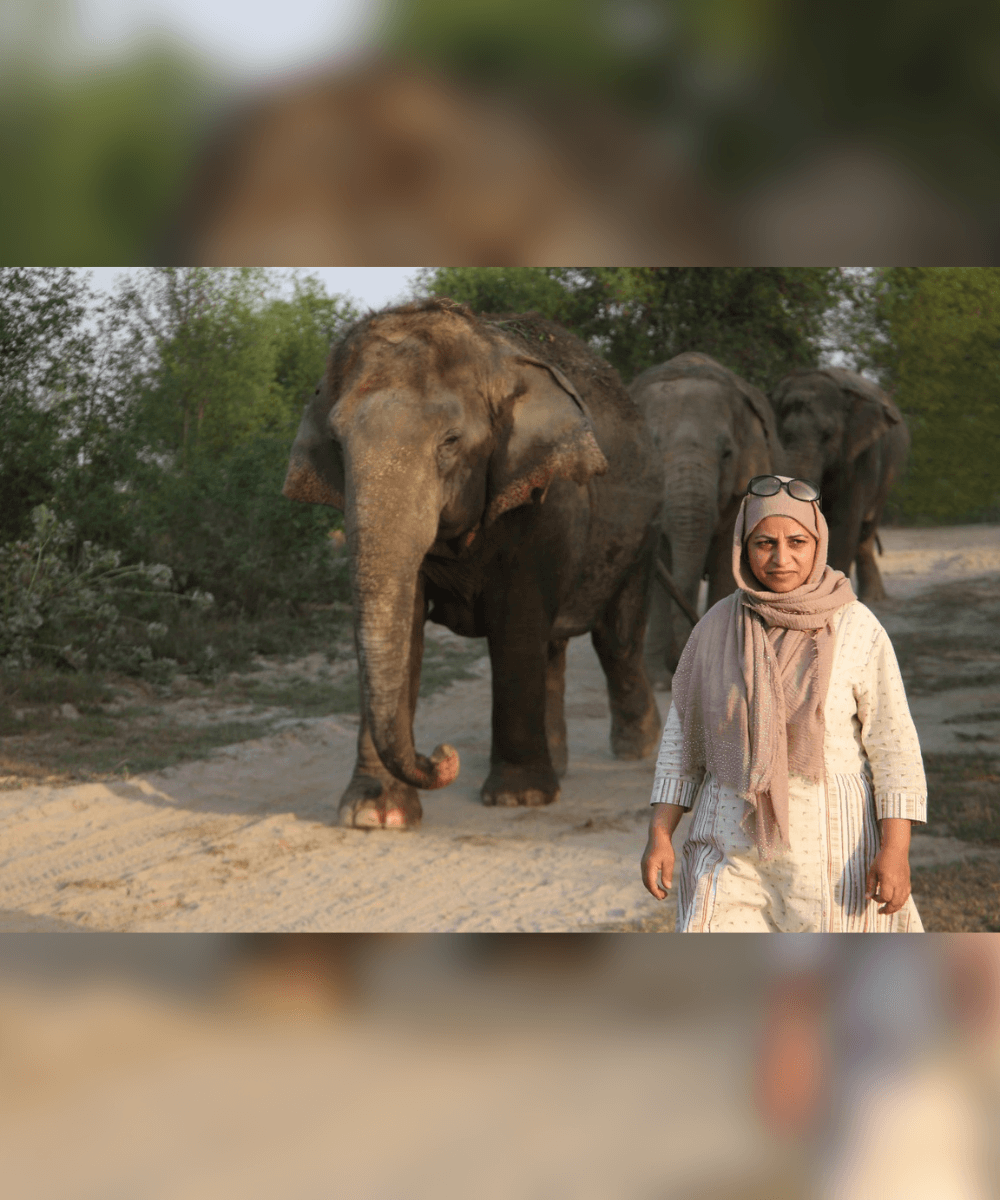

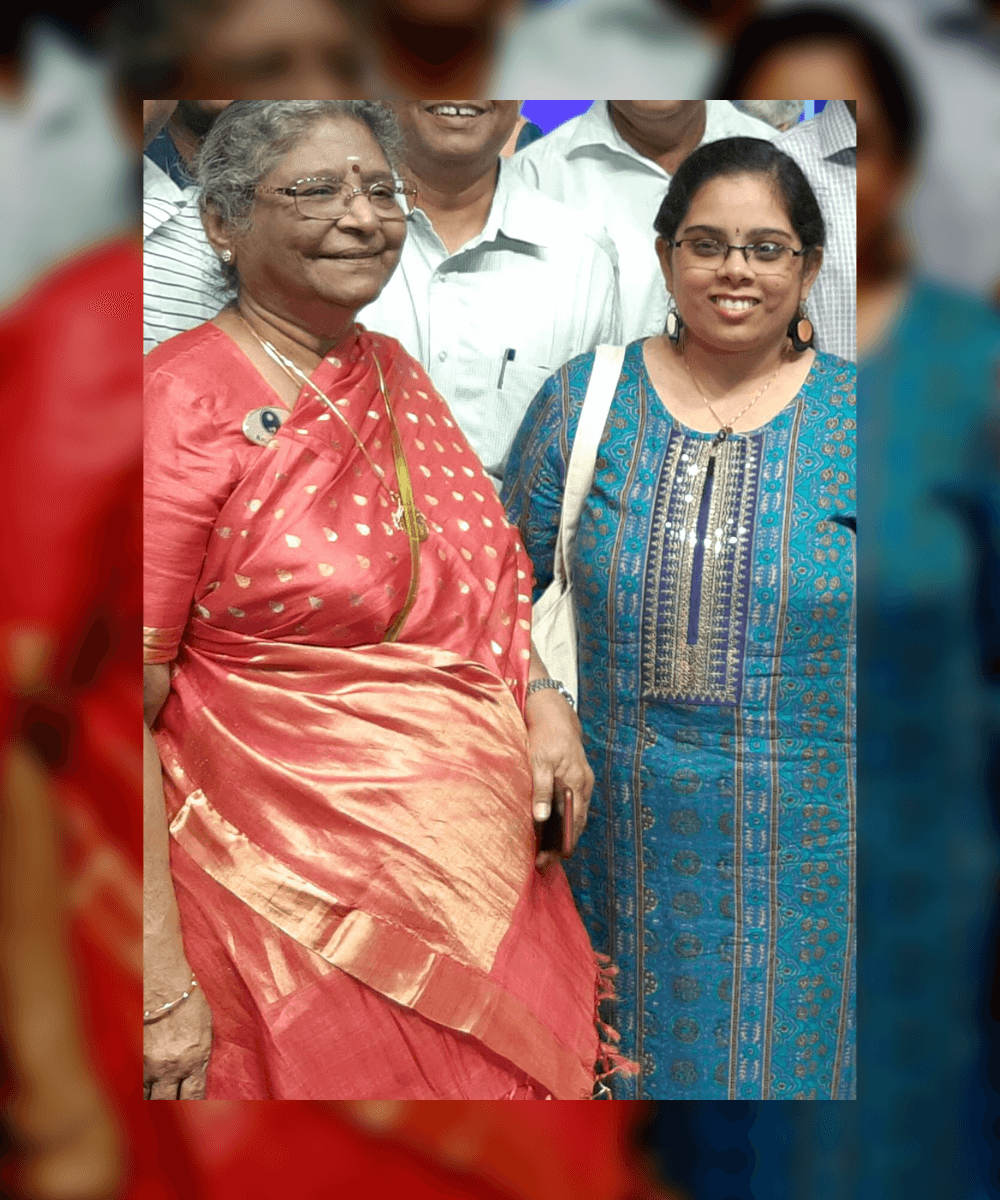

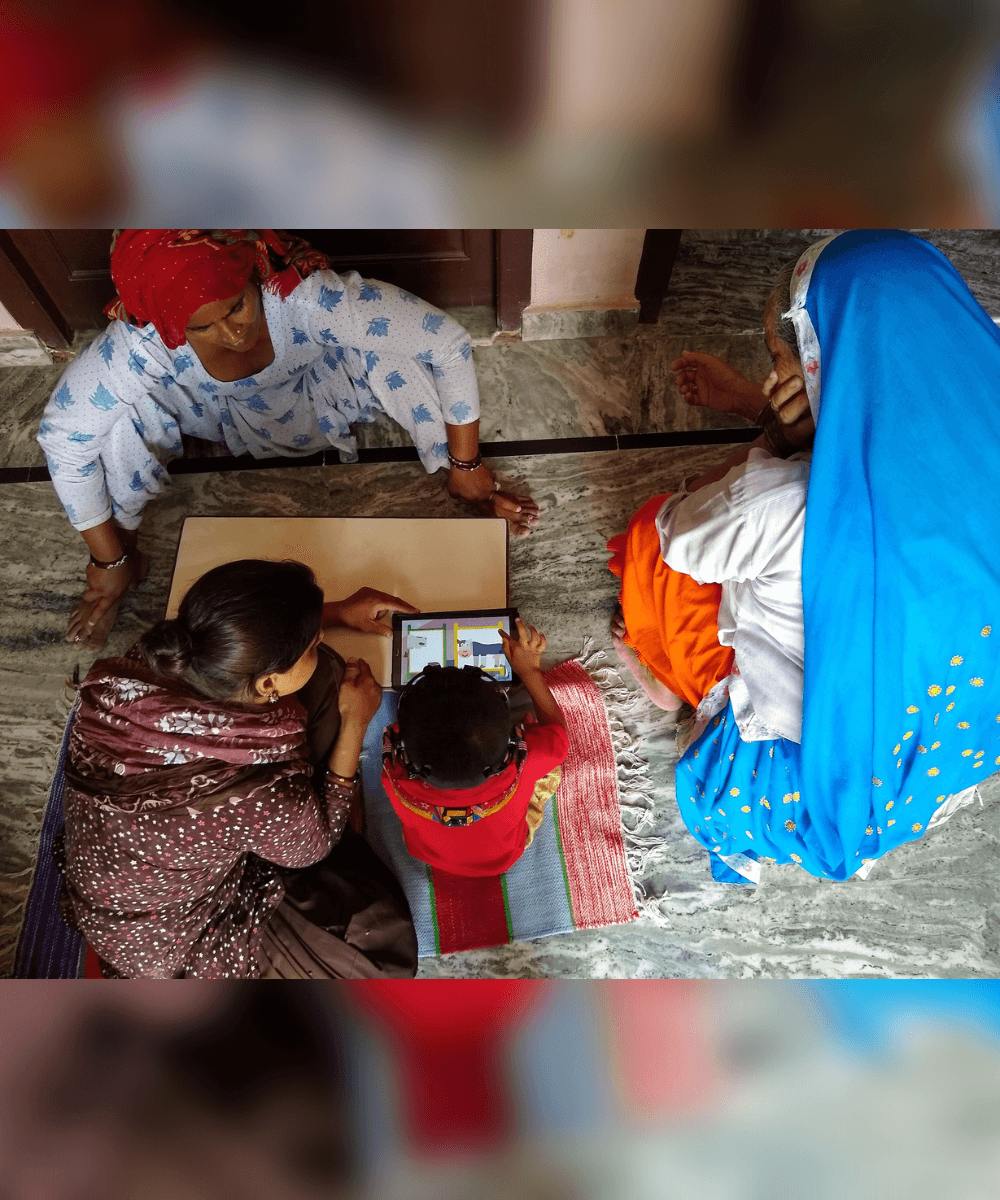

Dr Supriya Bhavnani’s research attempts to empower non-specialist community health workers to detect neurodevelopmental delays in young children

Dr Bhavnani’s team aims at creating simple tablet-based neurophysiological assessment tools that children as young as two years old can work with

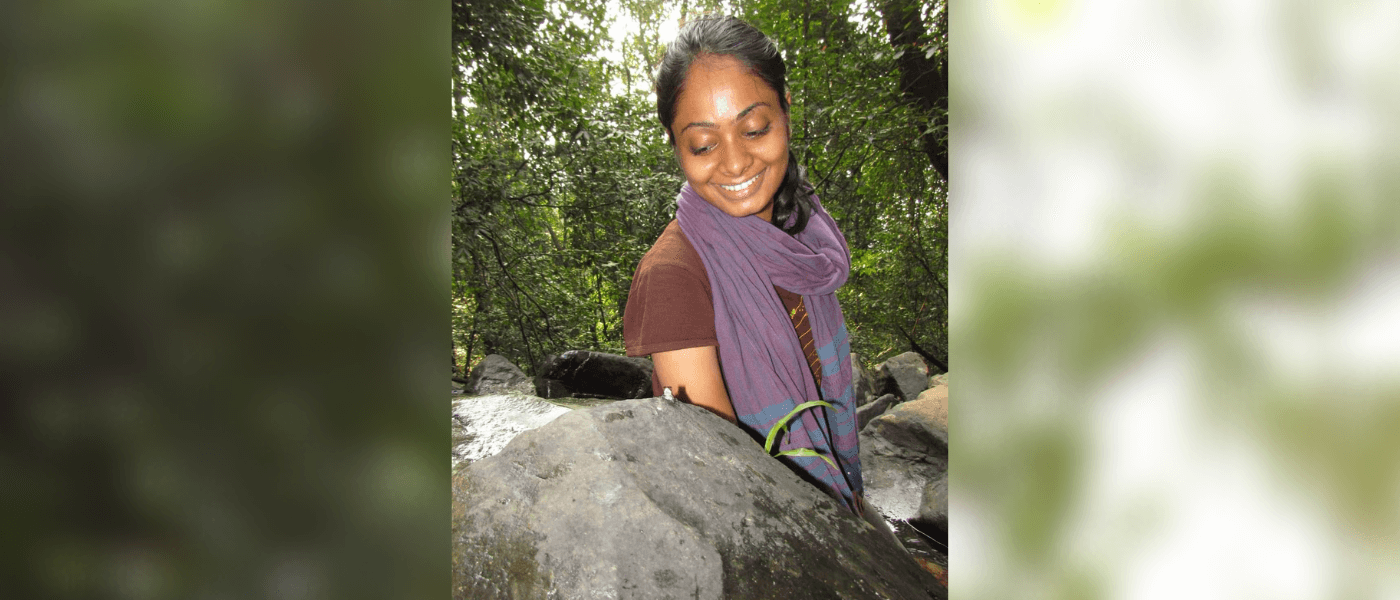

Dr Supriya Bhavnani was on maternity leave when we first connected. Speaking passionately about her research and the multidisciplinary nature of the project she handles, she took breaks to attend to her infant each time he stirred awake and sought his mother’s attention. In those moments of seamlessly moving from discussing her research into translational neuroscience and soothing her infant son shone the irrepressible and cohesive spirit of women’s work.

The objective is to create tools validated by evidence, that can be taken out of controlled, expensive and specialist settings of urban clinics, into low-resource settings…

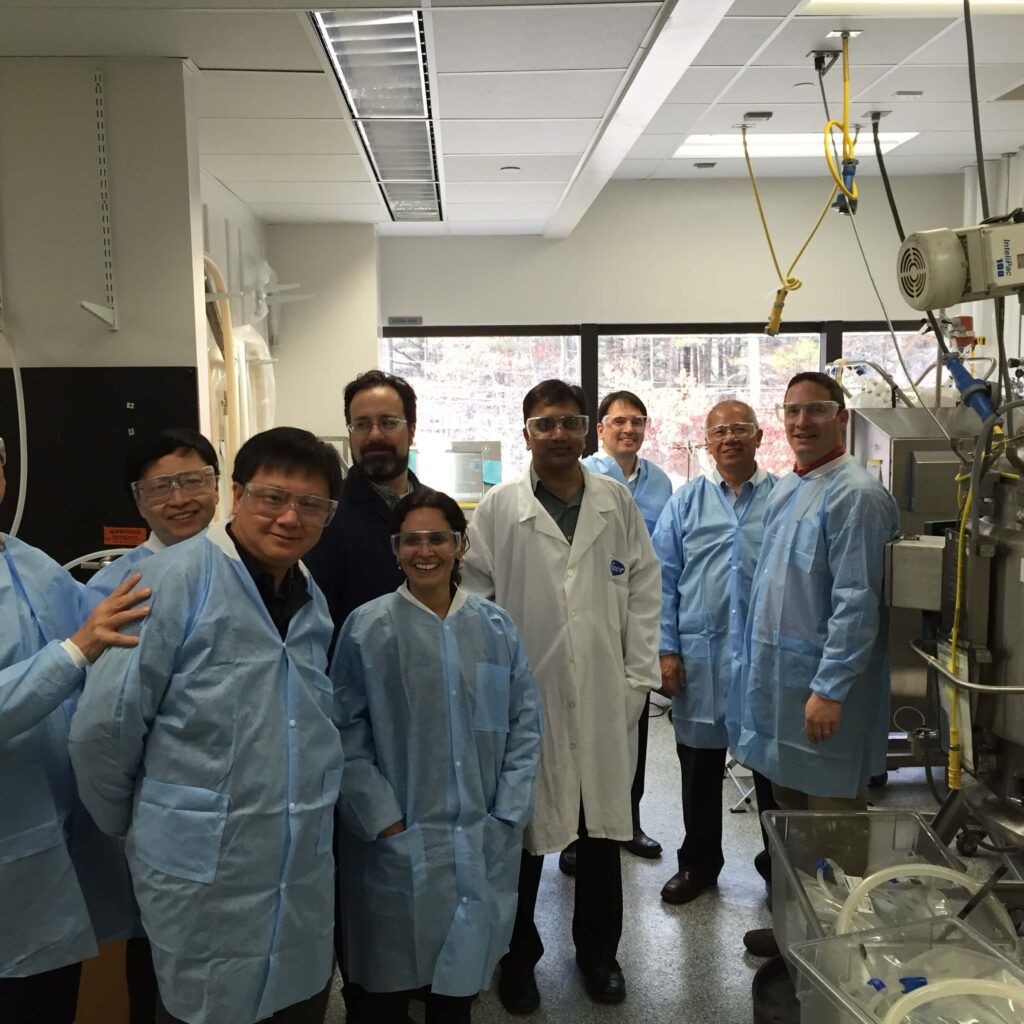

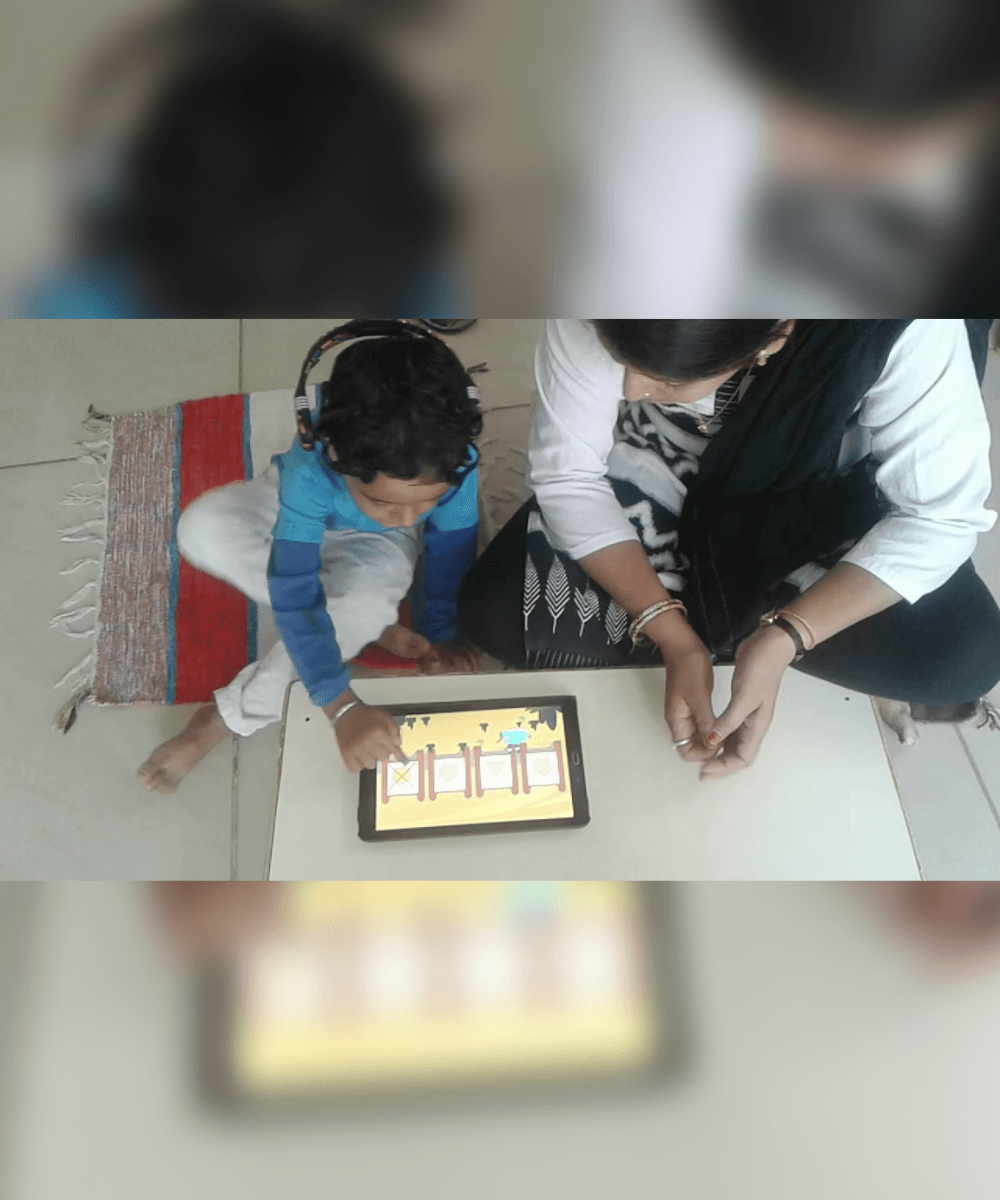

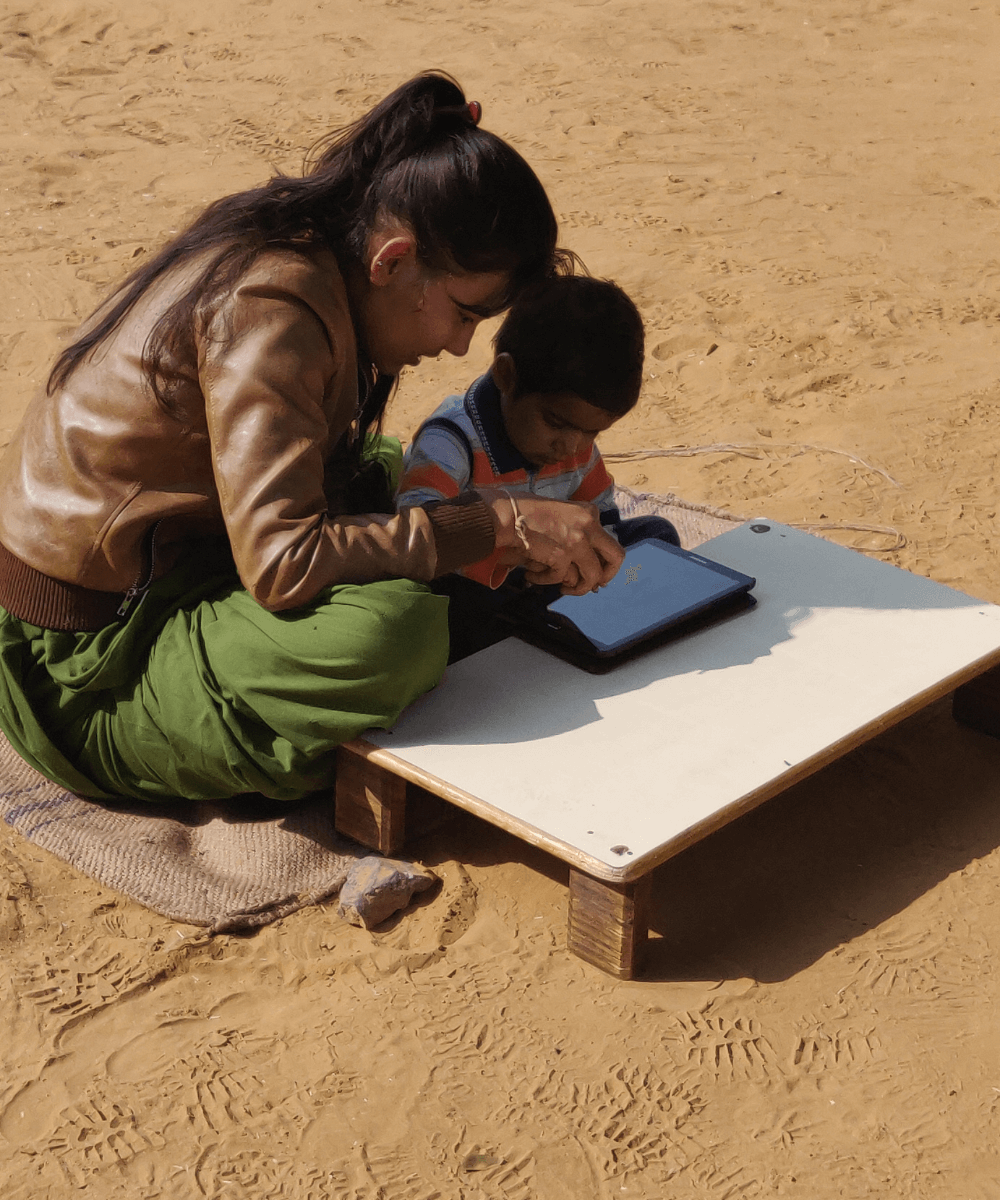

Bhavnani (38) is a neuroscientist at Sangath, a mental health organisation headquartered in Goa. Her primary area of research is neurodevelopment in young children. She is the co-principal investigator of multiple multidisciplinary and global projects involving neuroscience, cognitive psychology and developmental paediatrics, as well as engineers and app developers. The team aims at creating simple tablet-based neurophysiological assessment tools, including games that children above two-and-a-half years can play.

The objective is to create tools validated by evidence, that can be taken out of controlled, expensive and specialist settings of urban clinics, into low-resource settings where they can be of help to all children — a rural PHC, an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) or anganwadi centre. The tools will measure development in cognitive, social and fine motor domains of children.

They also use Electroencephalography (EEG) devices, along with an eye tracker for a project titled Brain Tools. They have tested the EEG in the community in Delhi and Haryana through two different projects — Brain Tools and REACH. The collected data help index cognitive function and social development, and can serve as an important tool to detect autism.

Driven by Sangath’s guiding principle to make mental health services accessible and affordable by empowering the community, the team is evaluating the acceptability and validity of the EEG results, so it can be scaled up and administered through non-specialist community health workers.

Bhavnani’s research has shown that about 1.5 years are lost before the parents recognise delays and start looking for help. “If children are assessed regularly, we can identify those who may need help early,” she says. But expensive tools are not easily accessible to low-income households; fear of social stigma and lack of awareness among parents and the medical fraternity are the other barriers.

“We have to move away from a psychiatrist or child development specialist and think of a non-specialist. What can they do? From a single-child in a clinic to a universal approach — to reach all children.”

From that perspective, we realised we need the help of engineers who can replace something as sophisticated and expensive as an eye tracker with a webcam video that can be taken of the child. We also needed specialists in computer vision and machine learning to develop algorithms to extract data from these videos. So we collaborated with IIT Bombay,” she says.

Before the project pilots began, they got people from different disciplines together in 2016, “most of them speaking [scientific] languages the other could not understand. But there was a general enthusiasm about the work,” says Bhavnani, about the multidisciplinary effort with domestic and global partners such as the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), the UK.

… like a rural PHC, an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) or anganwadi centre, where it can be of help to all children

The tools will measure development in cognitive, social and fine motor domains of children.

The American Psychiatric Association describes Autism Spectrum Disorder as a complex neurodevelopmental condition that manifests early in childhood and is characterised by social communication and interaction impairments, restricted interests and increased repetitive behaviours. The global prevalence of autism is estimated to be 1 in 132 (Baxter et al., 2015). A recent study conducted in India found similar prevalence rates; that of 1% in the age group of two to six and 1.4% in six to nine (Arora et al., 2018).

Global mental health expert and Sangath co-founder Prof Vikram Patel explains “brain development in the early years of life is the single most important predictor of lifelong success in education and beyond. However, most often, it is identified in school, where the children are categorised as having learning difficulties. By this time, the golden window of opportunity to intervene early has long passed. This is the challenge which the work Supriya Bhavnani is leading is trying to address.”

Bringing neuroscience into the public health system

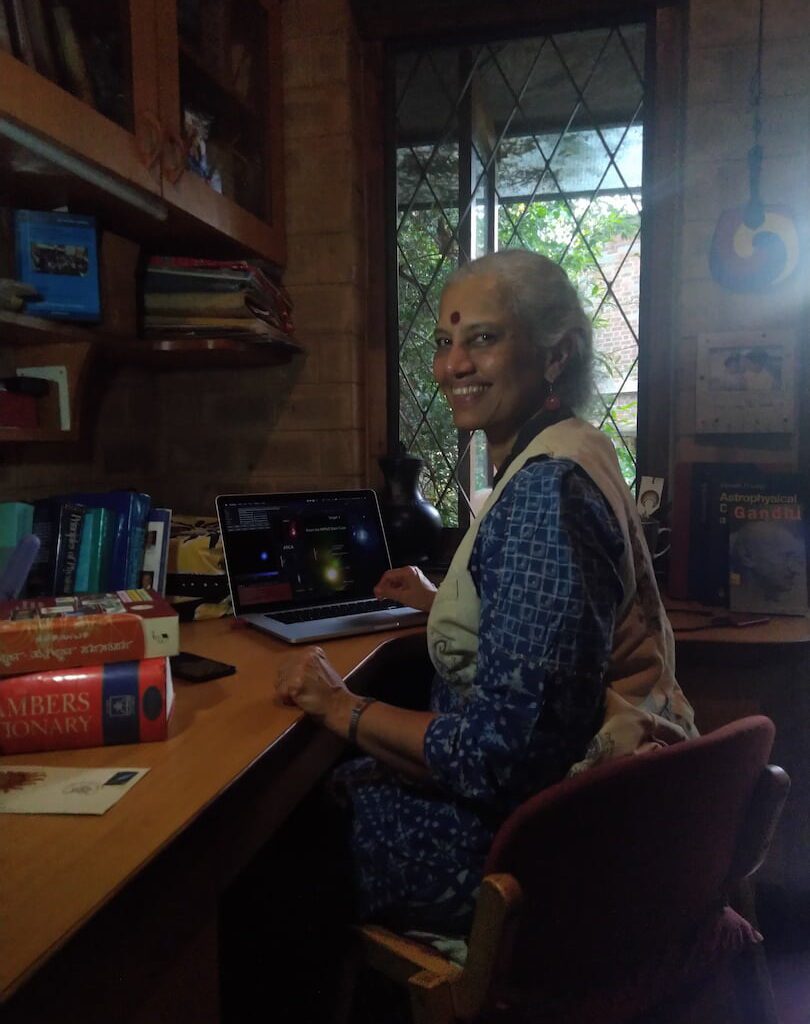

“I always loved the biological sciences and wanted to pursue research. After a Zoology major from Delhi University, I went to the University of Leicester for a Masters in Genetics,” says Bhavnani, who also pursued her PhD in the UK in genetics on the circadian rhythms of Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly).

“The European Union was putting together research on circadian rhythms. We studied the genetic architecture of these rhythms and behaviours when the insect was in its natural environment. We let it see sunrise and sunset and experience temperature variations,” she explains. That was 2010. “It was an out-of-the-box PhD. We struggled quite a lot to publish it,” she recollects.

Eventually, it was published in the respected scientific journal Nature, when Bhavnani was doing her postdoctoral research at the National Brain Research Centre (NBRC), Manesar. “That publication propelled my career,” she says.

During her NBRC stint, she felt a calling to work on the development of the brain and degeneration, autism and dementia. She set up the Drosophila research infrastructure at the organisation. Around this time, she won the INSPIRE fellowship of the Department of Science and Technology, which she credits for her growth as a scientist. INSPIRE gave her the flexibility to shift focus from pure sciences to “translational work”.

“I kept thinking about what comes after the fellowship. Having a student migrate into an organisation as a faculty is not easy in India. I faced roadblocks,” she says. In addition, it was difficult to do “out of the box” research in pure biological sciences in India.

Bhavnani reached out to Prof Patel to foray into mental health research. On his advice, she moved her INSPIRE grant to work under his mentorship at the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI). “Patel was keen to put a team together that worked in neuroscience, translating the knowledge of neuroscience into diagnostics and intervention the community can benefit from,” she says.

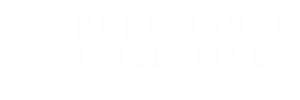

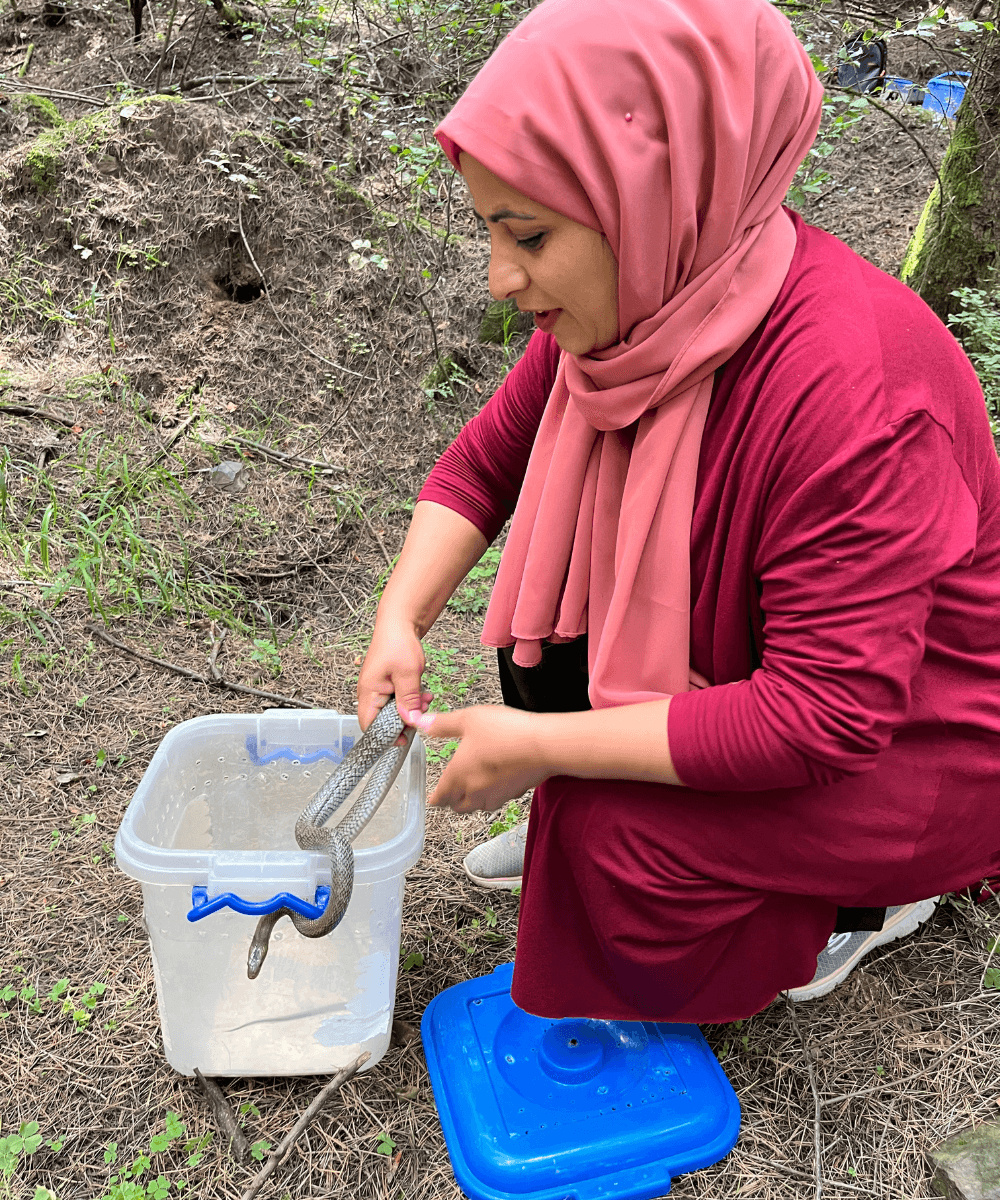

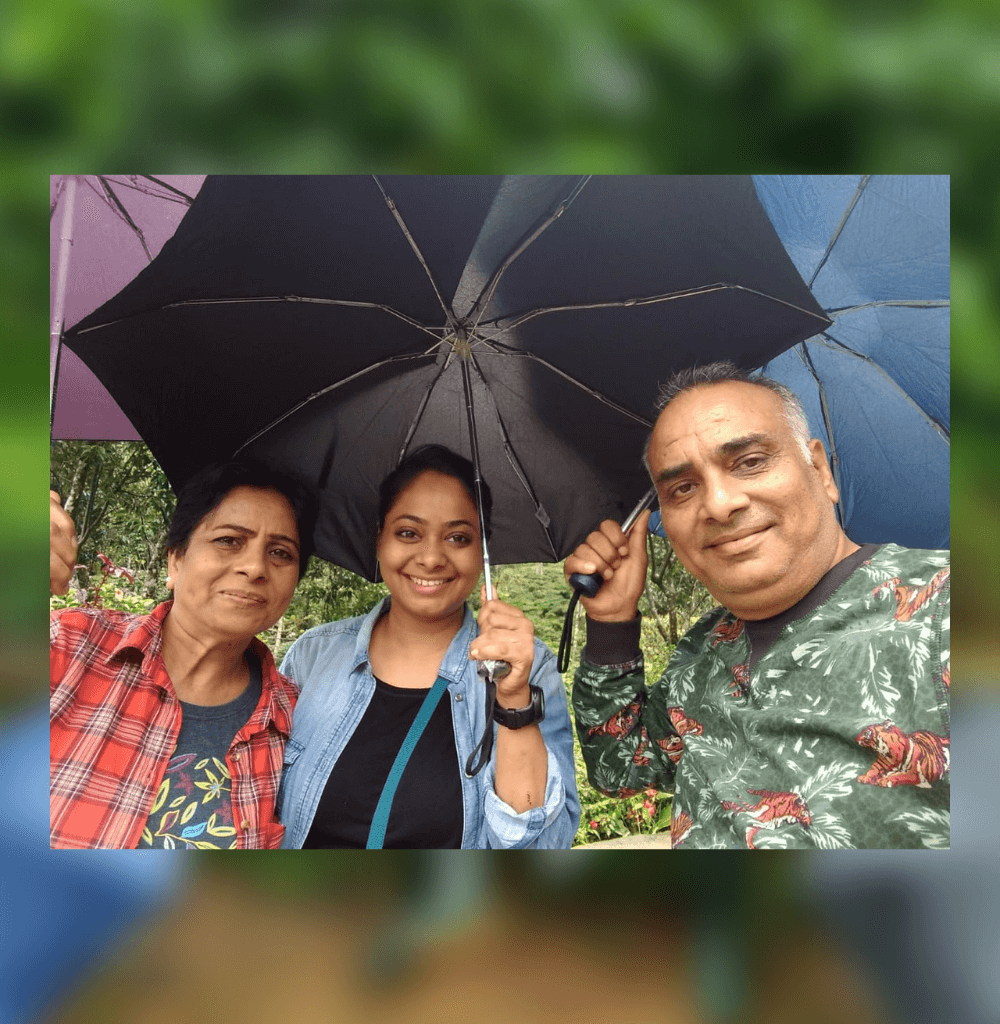

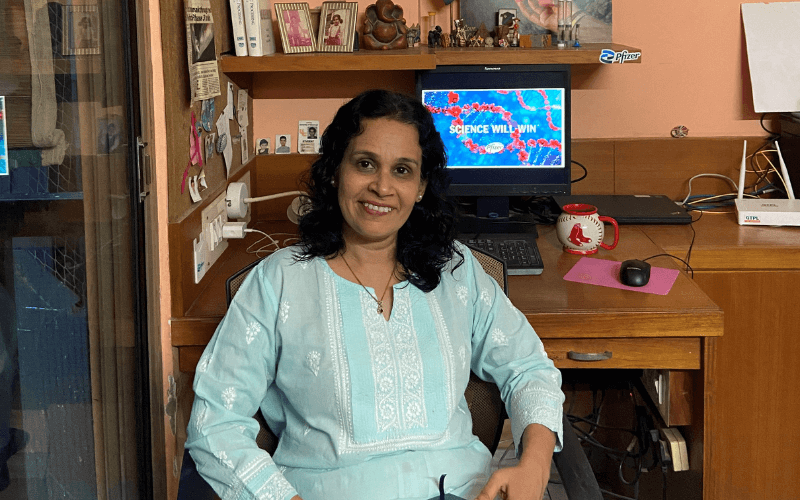

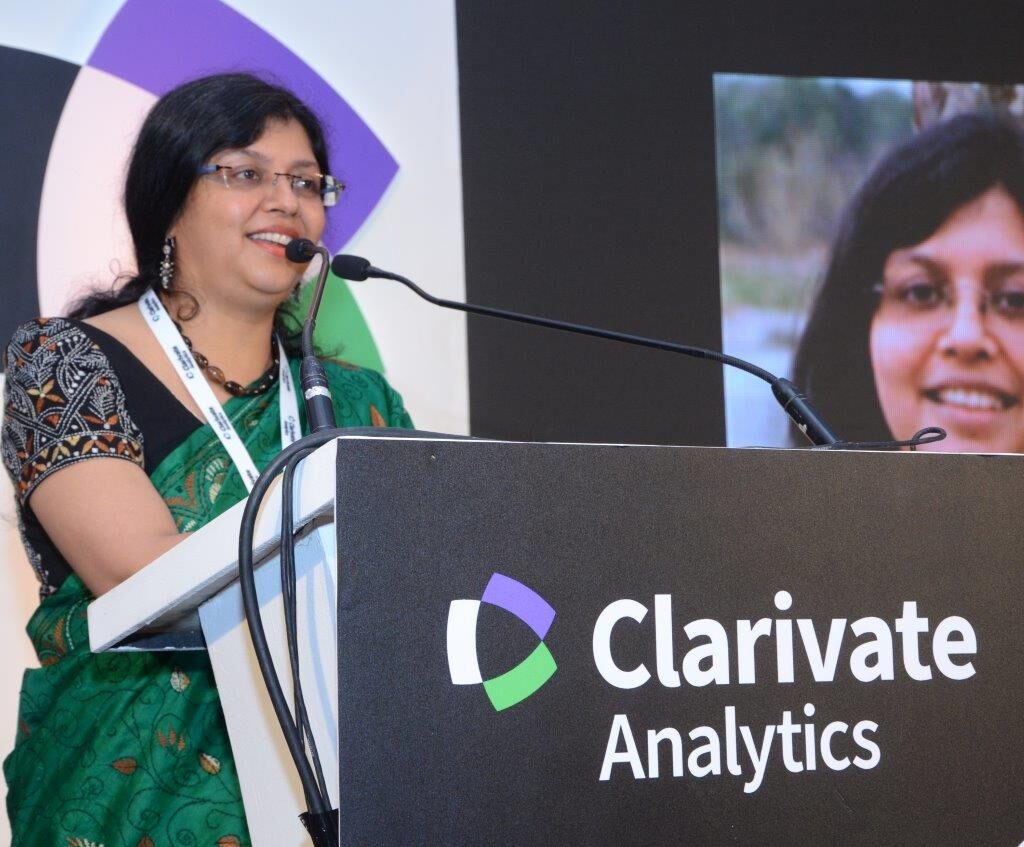

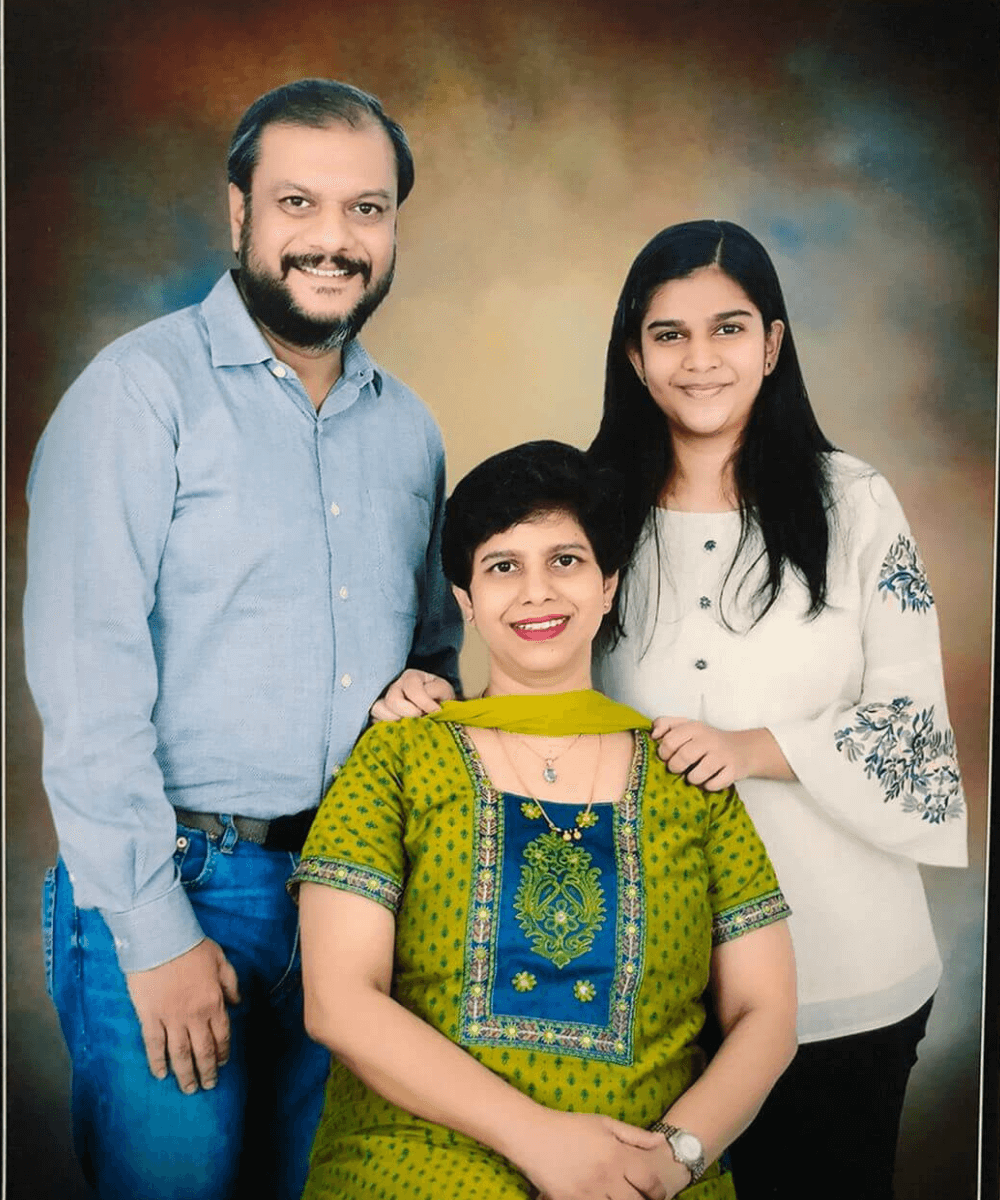

Dr Supriya Bhavnani is a neuroscientist at mental health organisation Sangath, focused on research around neurodevelopment in young children

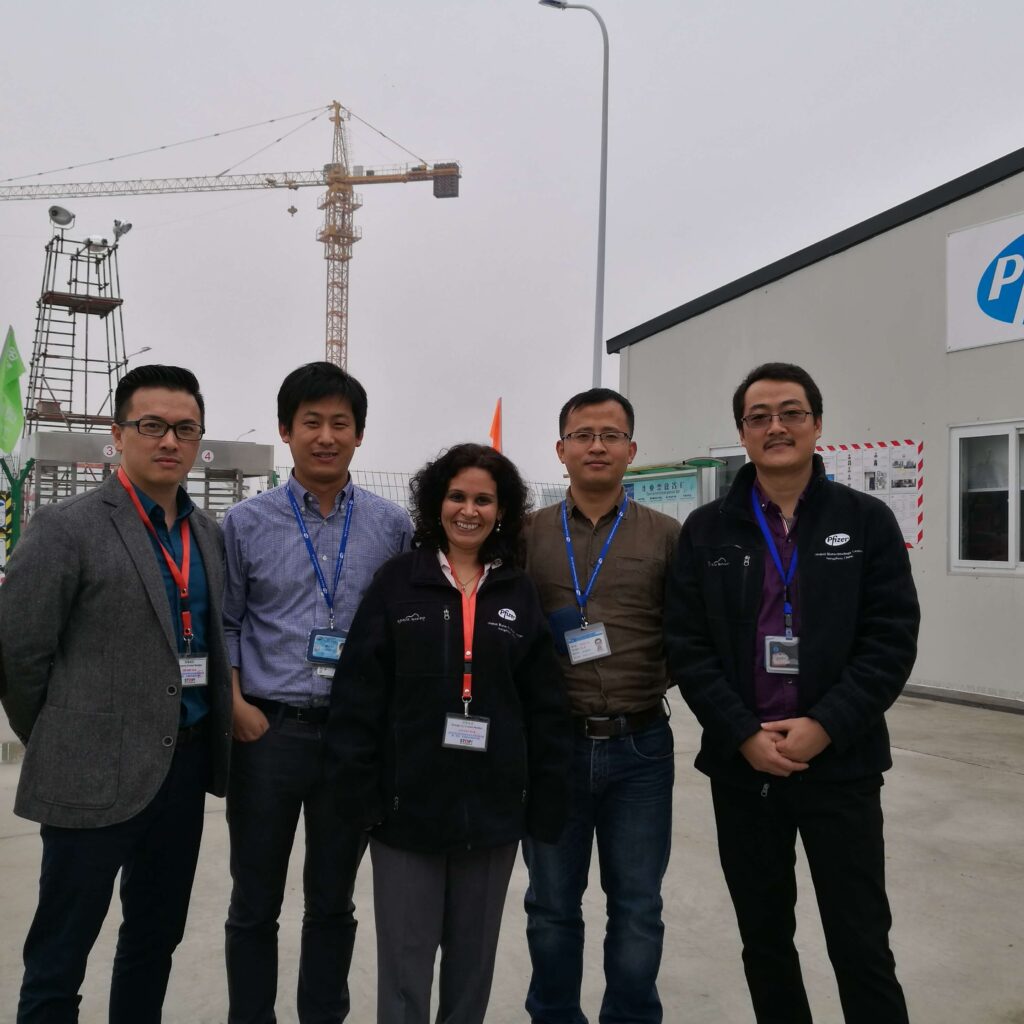

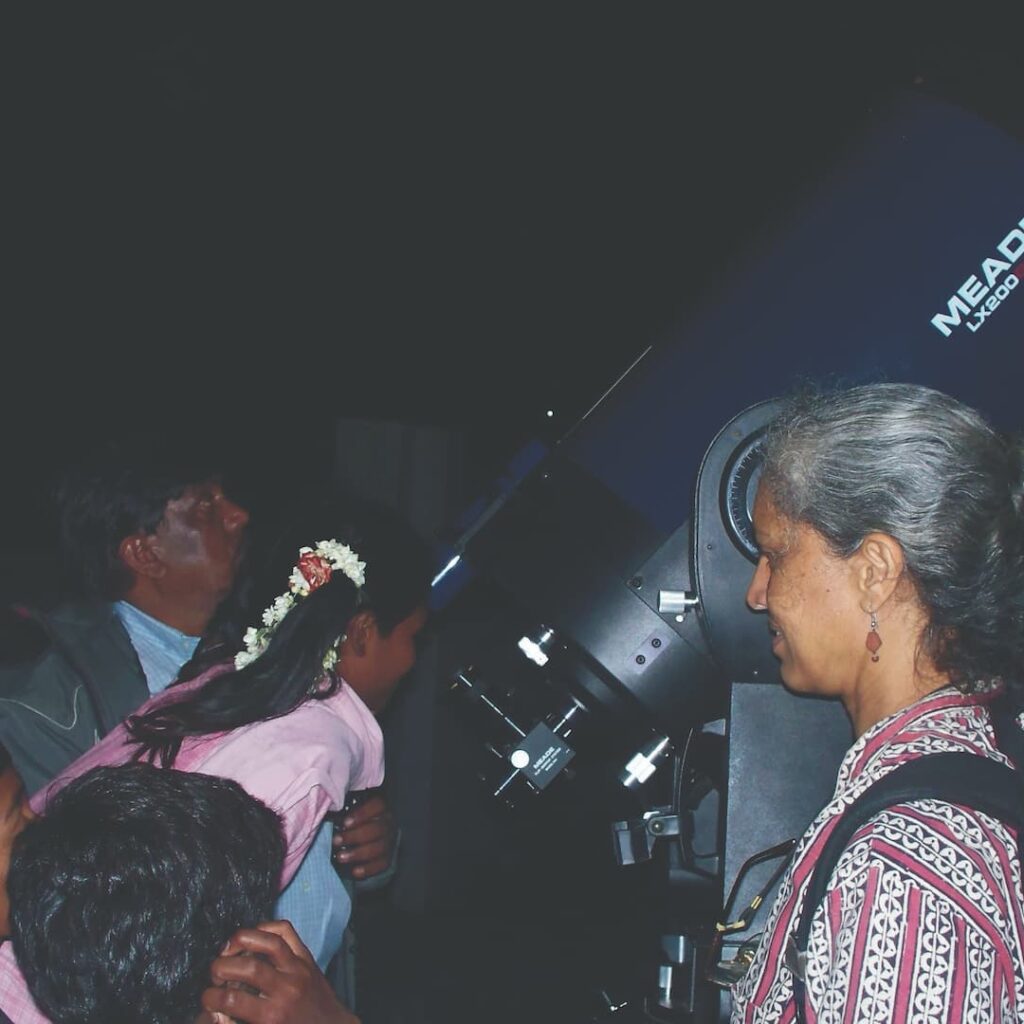

Dr Bhavnani presenting her findings (Source: Twitter)

The decision took her closer to the people she wanted to build solutions for. “The watershed moments in my scientific career were publication in Nature, and winning and moving my INSPIRE grant from the NBRC to PHFI. We started brainstorming about how to translate neuroscience into something that people can benefit from. In our case, we chose child development, as a team.”

Bhavnani changed her INSPIRE research question to study the ‘barriers and facilitators to getting an autism diagnosis in India’, and collaborated with the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Delhi. She studied what parents went through, the average number of doctors they consulted before getting a definitive diagnosis, what advice they got… all leading to “why does it take so many years for a child with a developmental problem to be recognised by parents, and then diagnosed.”

Alongside, Bhavnani, cell biologist Dr Debarati Mukerjee, psychologist Dr Jayashree Dasgupta, and neuroscientist Dr Georgia Lockwood Estrin from the LSHTM worked on the question of translational neuroscience, guided by Dr Gauri Divan and Prof Patel. They put together multidisciplinary experts from across the world in the child development and autism space and got a grant for pilots christened REACH (Integrated Assessment of Cognitive Health) and START (Screening Tools for Autism Risk using Technology).

In 2019, when the pilots were about to end, a grant from the UK’s Medical Research Council stitched together a larger project called STREAM (Scalable Transdiagnostic Early Assessment of Mental Health), which included REACH and START. “It examines if we can actually draw growth charts for brain development the way we draw for height and weight,” she says. The projects run across India and Malawi in Africa — testing 4,000 children in the age group of zero to six to measure an average two-year-old in cognition and social development.

Challenges before the health system

“Addressing the challenges in assessing early life brain development and offering tailored interventions to families require a convergence of diverse scientific disciplines, for example, neuroscience, digital science, clinical science and population health science, which have historically been siloed from one another. Supriya Bhavnani is an outstanding example of such a convergent science approach, for she is originally trained in basic neuroscience, focused on cells and genes, but is now working at the other end of the translational continuum, i.e. in populations,” says Prof Patel.

“We still have a fair amount of work to do before we feel confident to take this to a non-specialist. One positive is that we have always worked with women from the community,” says Bhavnani. ASHAs are delivering a project on autism led by Dr Gauri Divan, the director of Child Development Group at Sangath.

It is heartening to see families so ready to give us hours of time, answering questionnaires… Right now, we are on the detection side of it. In parallel, our child development team at Sangath is working on interventions. It is a crucial linkage to have strategies that can help the child catch up.”

The other piece is transferring this knowledge to the ASHAs and anganwadi workers. Ultimately, the aim is to marry these two pieces of work and create a system where a child gets identified and course-corrected to be able to reach their full potential.

Edited by Rekha Pulinnoli