Posted on 12 August 2022

Professor Vidita Vaidya: Of being resilient and the science of resilience

By Saloni Mehta

She leads her life and undertakes her scientific endeavour with incredible curiosity, honesty, and a remarkable fighting spirit.

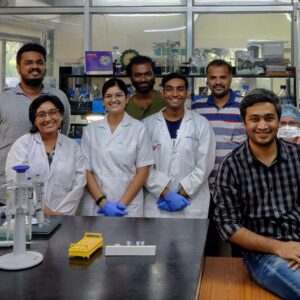

Professor Vidita Vaidya, conducting an experiment at the bench with one of her students during the Covid-19 lockdown

“The scientific community needs to acknowledge their privilege more,” says Vidita Vaidya, professor of neurobiology at Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, where she heads the Hutment Laboratory. “They insist on meritocracy and conveniently forget the massive amounts of privilege accumulated over centuries that gets couched as merit. Meritocracy is a crap argument,” she adds emphatically.

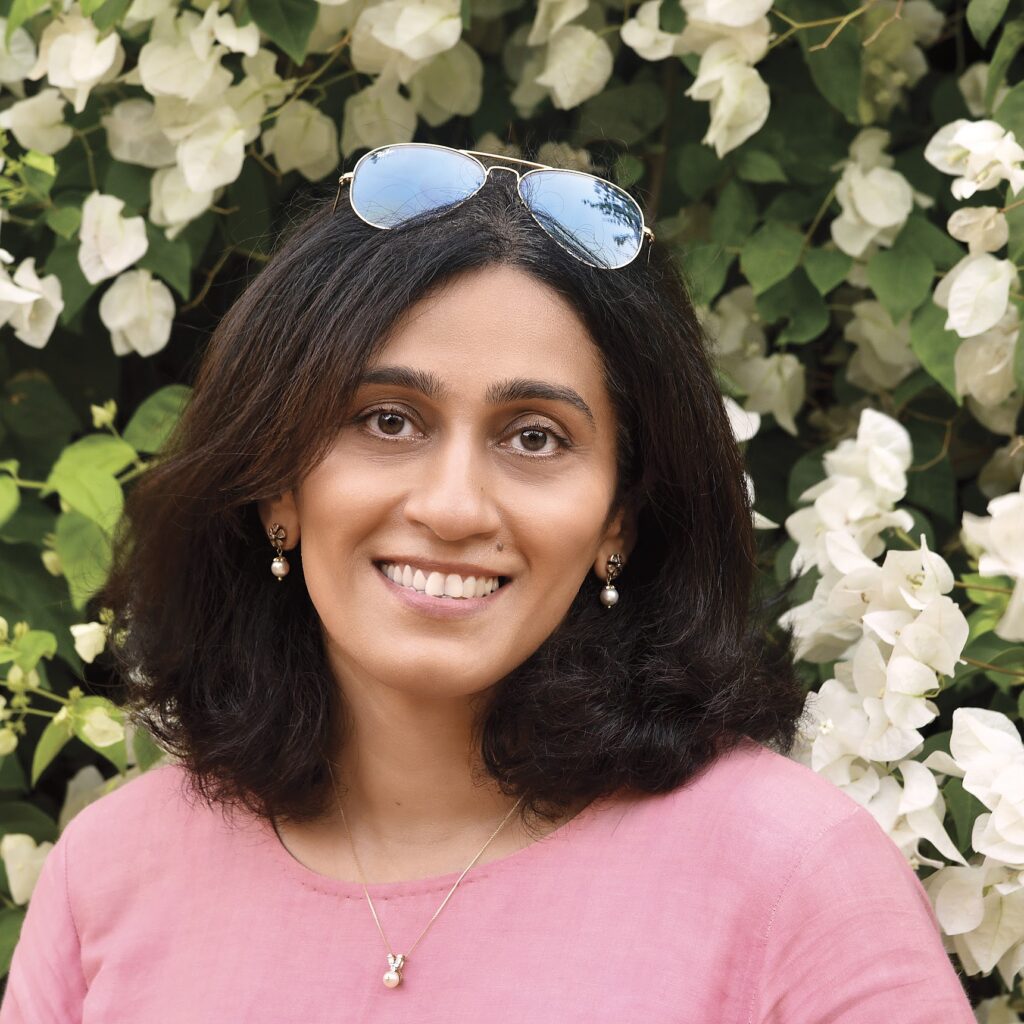

Professor Vidita Vaidya

She believes that this talk of privilege is often missing from scientific tables and that the system is stacked against anyone who is not a cis-het male from the upper caste and class. “All our diversity and equity initiatives operate within a system that’s inherently made for only a certain kind of individual. And the system repeatedly weeds out anyone who does not fit the mould.”

The number of people who quit science because of systemic challenges is tragic because, as Professor Vaidya puts it, “these were precisely the voices and the alternate viewpoints that science needed”.

“The questions that are asked under the scientific endeavour are directly impacted by who gets to ask them. So when only a selected group is allowed to do science, the science that’s produced leaves everyone else out of consideration.”

'Her'story of privilege

Professor Vaidya works to understand how circuits of neurons in our brains affect our emotions and how early life experiences impact this circuitry.

We are interested not just in what makes people vulnerable, but also in what makes them tremendously resilient," her voice brims with passion.

A recipient of the prestigious Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award, her research focuses on serotonergic psychedelics and the alteration caused in our brain by their use.

“Not that they are not nice, but I am not in it for the awards. I do science because I enjoy it, because the ‘aha!’ moments are tremendously rewarding, and I will continue to do science till I enjoy it. If and when I stop liking research, I’ll go open up a bookstore cafe,” she laughs, reminiscing about her days of growing up in libraries – browsing through books, colouring on the marble floor, reading, and enjoying the then scarce air conditioning.

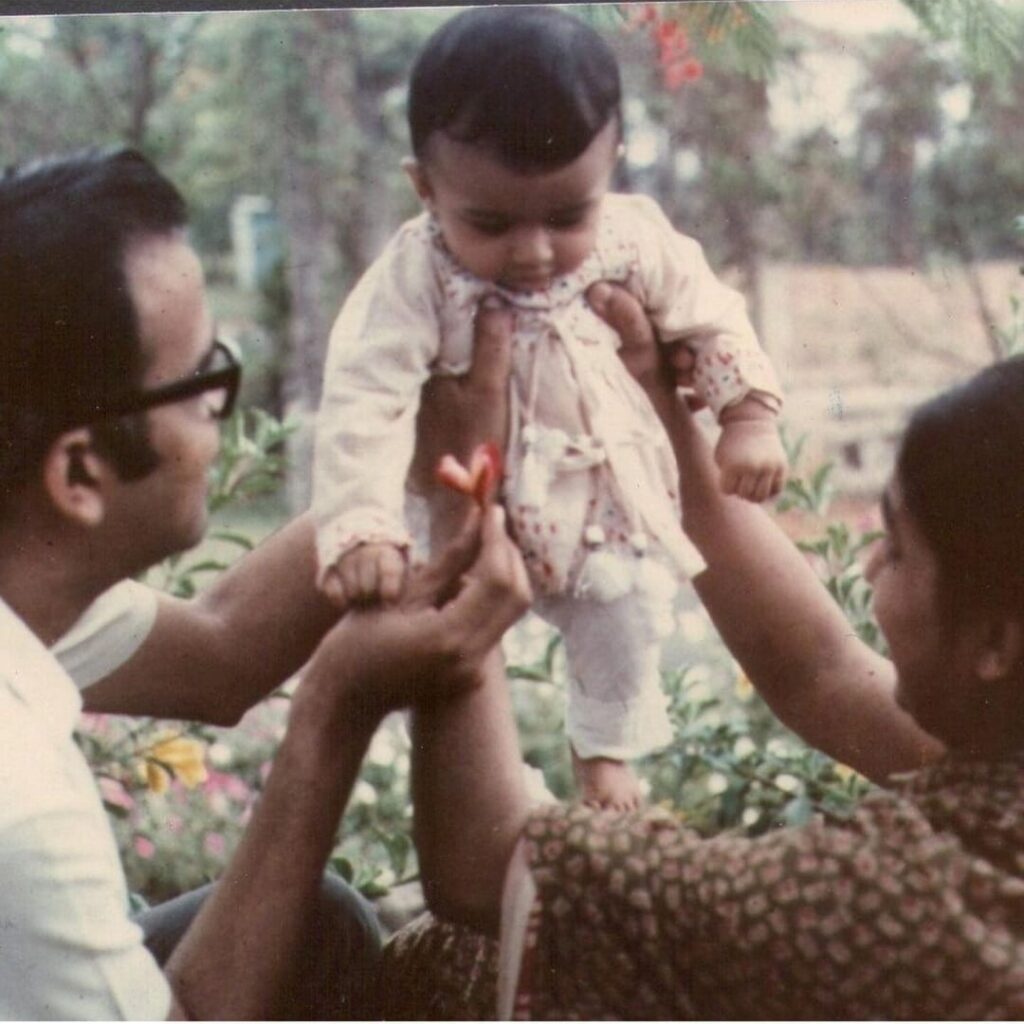

Recounting her own privileges, the neurobiology professor says that having a family that’s always believed in her potential made all the difference in her life. Being born to parents who were both clinical researchers and growing up on a research campus meant science was a dinner-table staple. This academic environment at home helped her realise fairly early that she wanted to pursue a career in biology.

“I knew my story was not that of a usual girl in 1980s India. I was a single child, raised by parents who always believed in my potential, grew up with researchers all around and had no boundaries around my dreams. Very few women had this privilege,” she recalls.

Her husband, daughter and in-laws have only added to this privilege through their unconditional support, she says, adding how lucky she was to find mentors and advisors throughout her scientific journey who believed in her, including the late Dr Ronald Duman, her doctoral advisor.

Vaidya believes she was made cognizant of her privileges very early in life through conversations with her grandmother, who had to drop out of school at an early age, and whose lifelong dream had been to acquire vast amounts of knowledge.

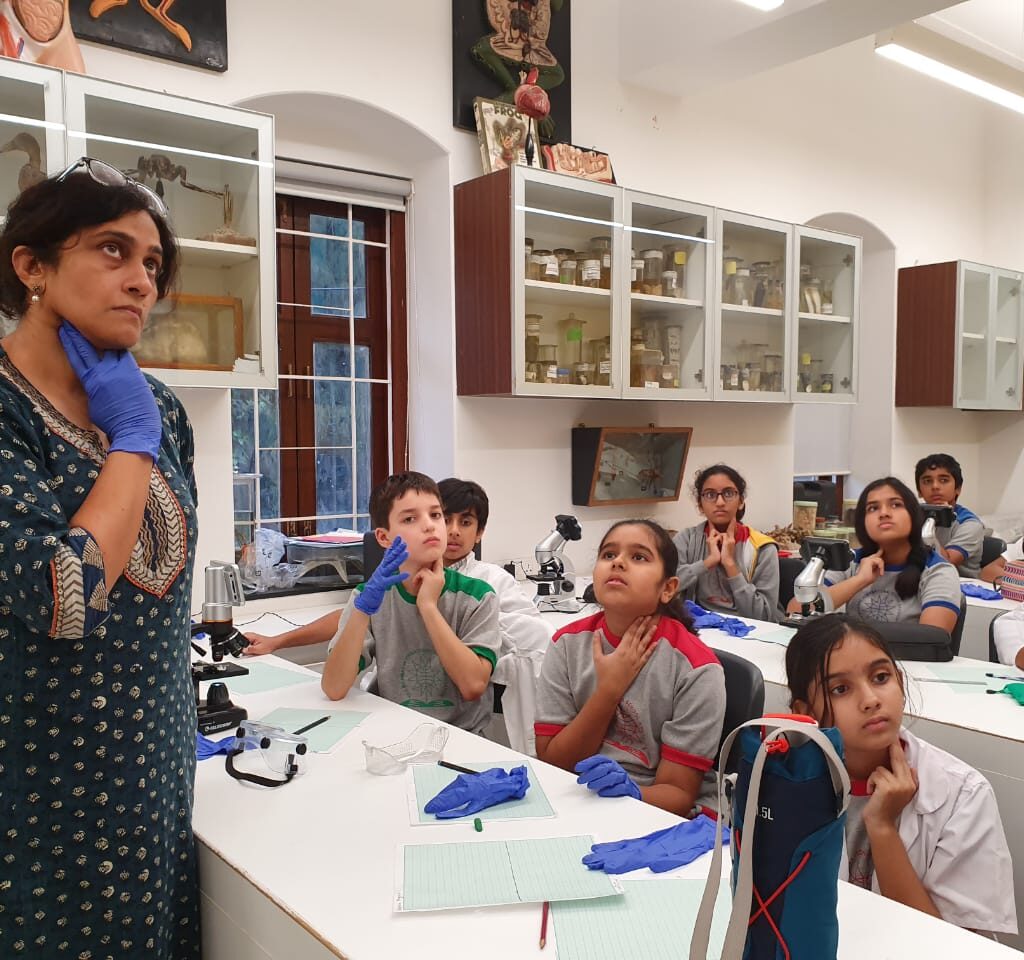

Prof Vaidya led a session on measuring shifts in pulse after exercise and linked them to neurotransmission as part of an outreach activity with the students of Bombay International School

She recalls, “My grandmother was one of the wisest people I knew. She had to drop out of school after the fourth standard to care for her older brother, but it was her dream to study. She used to say that she would study endlessly if she was reborn. Thinking about how this incredible woman with this desire to study had her education curtailed made my privilege very apparent to me.”

Celebrating 20 years of the Hutment Laboratory at Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai

Resilience and learning from failure

Despite receiving numerous accolades in the field of neuroscience, the professor is extremely honest about her failures. She says her favourite piece of research was a ‘serendipitous’ discovery, born after several failed attempts. She found out that serotonin regulates mitochondrial biogenesis, or the process by which cells increase mitochondrial numbers. The results, she adds, were hitherto unheard of, and she and her team, after several rounds of research, published their findings in a 2019 paper. Vaidya jokes that her findings were actually a “fluke”. Even her PhD experiments had initially failed, but her relentlessness had given her research a completely new direction.

“Failure is not an invalidation of your capabilities, it’s just a reality; some experiments just fail. And sometimes, when you stick around and look more closely at something that failed, you might find something you had not anticipated.”

Failure is inevitable in science for all, but how it impacts everyone is vastly different.

How much one believes in themselves affects how they navigate failure. So for anyone who's made to feel like an outsider — women, Dalits, trans people and other marginalised communities — failure becomes proof of their estrangement from science.

The re-imagination of this system is a task of gargantuan scale, she admits but refuses to despair. Her suggestion is to start with reimagining our central and state university spaces. “Our research institutes are ivory towers that gate-keep science and are detached from the rest of the world.”

She also emphasises the need for liberal arts and social sciences to permeate scientific journeys so that pre-set rules can be constantly questioned and revamped if found to be baseless.

Demystifying science and its realities

Professor Vaidya is also tremendously passionate about science communication.

If you cannot communicate your science properly, it does not signal anything about the complexity of your work. It just means you are just a bad communicator. It should be mandatory for anyone whose research is funded by taxpayers’ money to explain to the public what the findings were. This is a question of moral responsibility and there should be no room for excuses,” she says.

A scientist in the making: Vidita’s parents nurtured her curiosity and provided integral support in her scientific journey

To the question of whether it could lead to the oversimplification of scientific results, she says: “It is a disservice to the process of science to assume that the public does not have the ability to understand ambiguity. It is okay to admit that we can say only a set of things with a particular degree of certainty and that there are limitations and risks.”

The Hutment Laboratory’s website embodies this spirit of hers. Even a layperson can understand most of its contents. Besides, her students have translated its sci comm page into 11 other Indian languages.

Picture perfect: Vidita with her parents, parents-in-law and daughter

To young women looking to pursue science in an academic setting, her advice is to be prepared for the challenges of academia. She also advises them to be realistic and not put people up on pedestals; to recognise the problems with the system, especially if they are an ‘outsider’. “Find people whom you can talk to and among whom you find a sense of belonging,” she says, emphasising that it’s important to find mentors outside your theses advisors. Do not self-eliminate when looking to apply for something, she tells young women.

Try to hang in there, science needs you, and your voice matters.

![[11 Her PhD Advisor - Dr. Ronald Duman]](https://rukhmabai.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/11-Her-PhD-Advisor-Dr.-Ronald-Duman-300x300.jpg)

its good